- | 8:00 am

Too big? Too small? No, these office buildings are just right for housing

There’s a ‘Goldilocks zone’ for converting office buildings to housing—and this architect found it.

It’s time to admit it: Most empty office buildings are not turning into housing. That simple recipe for pandemic lemonade—offices people no longer use, combining with central urban locations where people want to live—is blissfully ignorant of a wide range of architectural and economic factors that make the vast majority of office buildings simply unsuitable as housing.

But while most are either too big, too new, too crowded, or too technically complicated to convert to homes, there’s a Goldilocks zone of office buildings that are just right for turning residential: Typically, they’re mid-rise, modestly sized structures built before World War II, with at least two sides fronting open areas or streets in neighborhoods near, but not directly in, the city’s dense financial center.

“That’s the sweet spot for conversion,” says architect and structural engineer Charles F. Bloszies. An analysis he conducted looking at San Francisco (but, importantly, adaptable to other cities across the country) finds that there are dozens of properties that make sense both economically and structurally to make the switch.

His San Francisco firm has been doing building conversions in the city for 30 years. Using publicly accessible data from the San Francisco Planning Department, he found at least 49 properties that fit all of those characteristics.

“Office buildings are sometimes hard to convert to residential because the floor plate’s big or they’re wedged between other buildings and don’t have enough street exposure,” Bloszies explains. Having two or more entire sides of a building facing the open space along a street allows light and air to penetrate more easily than one shadowed and suffocated by neighboring structures.

Urban density, especially in a city like San Francisco, makes for a lot of buildings—prototypical high-rises with modern, so-called Class A office space—without that access to the elements. But Bloszies’s analysis found that there are many structures that don’t have those issues, mostly four- or five-story prewar buildings that have operable windows and nestle into neighborhoods instead of towering above them. These properties, Bloszies says, are perfect candidates for conversion.

“On the technical side we haven’t learned anything new that we didn’t quite know before,” he says. “It’s simple, straightforward stuff, like you need light and air.”

FINDING THE GOLDILOCKS ZONE IN YOUR CITY

The kind of analysis Bloszies undertook could be done with public information in nearly any city. Savvy developers, project-ready architects, or even proactive city planners could quickly identify office buildings in this Goldilocks zone and either start pursuing projects or fast-track the zoning changes that could help them take shape.

Now is the time to get started. With rising office vacancies, growing demand for housing, and relatively low real estate costs, office-to-housing conversions are more feasible than ever, according to Bloszies. “We’re at what you might call a critical storm of opportunity for converting offices to residential,” he says.

Real estate agent Justin Fichelson is on the hunt for a building in the Bay Area’s Goldilocks zone. The founder of real estate brokerage Avenue 8 and former star of the Bravo television show Million Dollar Listing San Francisco says smaller, older, so-called Class B office buildings are potentially historic deals right now.

“I would love to get a small building that has potential for mixed use,” he says. The market is primed for former offices being converted into four or five stories of apartments, with space for retail on the ground floor. Fichelson recently lost out on one building like this in San Francisco, but he’s actively searching for others there, as well as in Los Angeles. “Now more than ever is a great time to buy. It’s the bottom of the market for properties like that,” he says.

With deeper pockets, Fichelson says he’d even be willing to snap up some of the larger Class A office buildings downtown. With their natural-light-starved floors and lack of operable windows, they may not be ideal for conversion to housing, but that doesn’t mean they’re solely suitable as working office space. Fichelson says updated urban planning policies may soon allow big office towers to serve as logistics facilities, data sites, or daycare centers. “Eventually the city’s going to rezone and these buildings are going to be repurposed for whatever demand is out there, especially if they’re in a prime location,” he says.

Housing probably won’t be in their future, though. The main challenge is the size of most modern office buildings, which can be massive, block-sized rectangular structures. In many downtowns, the towers that define the skyline were built after World War II, in a heady era of economic growth. The interior spaces are huge, with such great distances from the center of the building to the windows that turning them into residences would leave most occupants in the dark. And even if they did have windows, they probably couldn’t be opened. “I’d say like 99% of them don’t have operable windows,” says architect John Cetra of the New York-based firm CetraRuddy. “They were like hermetically sealed boxes.”

Other concerns include taking out elevator shafts that are no longer needed for the reduced foot traffic, and rejiggering mechanical systems so that each apartment could have its own climate controls. “As it becomes more obvious that there’s a lot more to it, I think people will be more selective about the buildings they’ll actually propose,” Cetra says.

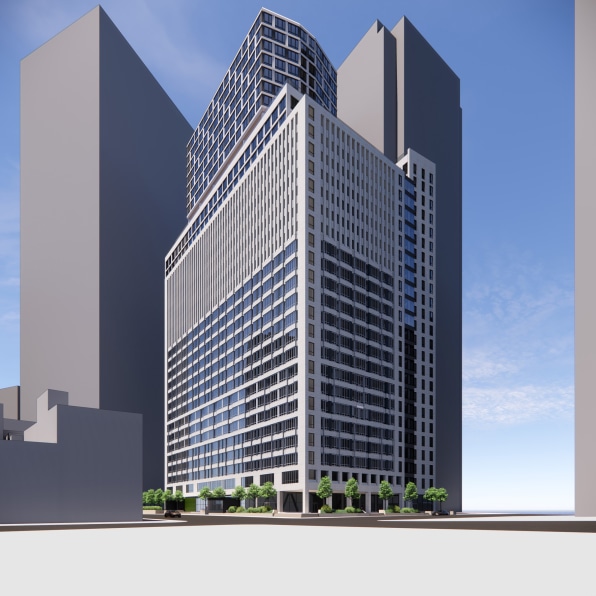

But the Goldilocks zone is different from city to city. One building that made sense to convert is a former bank operations center located at the tip of lower Manhattan. Architects at CetraRuddy reworked its bunker-like brick facade to carve out the windows residences need, and upgraded the mechanical systems for modern living. Crucially, they solved the problem of the building’s large floor sizes by cutting two 19-story courtyards into the center, providing the light and air needed to make interior residences livable. “It’s like a new facade that’s created within it,” Cetra says.

And under New York’s floor area ratio zoning rule, which defines how tall a building can rise based on its overall square footage, the removal of that floor area enabled the developers to shift square footage to the top of the building, adding an additional 10 stories of apartments. “In this case it’s making economic sense for a developer to do that,” Cetra says.

It’s an approach CetraRuddy has used in other projects as well. Cetra says beneficial zoning laws make that kind of design move workable, and that other policy changes will likely make such projects even more viable, in New York and beyond. “I think it’s a great thing for cities to allow more and more of these conversions to take place,” he says. “And I suspect they will.”

Bloszies says San Francisco is primed for an office conversion trend. “It strikes me as being similar to the dot-com boom we had here around 2000. Light and heavy industry had left San Francisco, so there were a lot of big vacant warehouse buildings,” he says. “All of a sudden the tech world says these are really cool.”

A vacant five-story office building may not have that same architectural cachet, but neither did those empty warehouses at first. Replace five floors of day-use cubicles with residences, throw a café or restaurant on the ground floor, and suddenly a boring former office building becomes much more interesting.

That’s the bet Fichelson is planning to make as he shops for an empty office building in the city. Even so, he knows it will be a gamble, and one many of the real estate investors he knows won’t take. “Most people are probably going to shy away from it because it’s tough to pay the bills and you’re going to have to weather the storm,” Fichelson says. “I think 10-plus years from now people are going to say, ‘I could have gotten this all-time deal on prime real estate.’”