- | 8:00 am

Why you should be designing for your parents, not your peers

Why tech has an age-bias problem, and what we can do to fix it.

I’m building a business in senior tech. And yes, I’m aware that—for many of you—that will sound like an oxymoron: “Tech for seniors? My [insert family member here] can barely use their phone!” But prepare to be surprised: Here’s what I’ve learned about how wrong we all are.

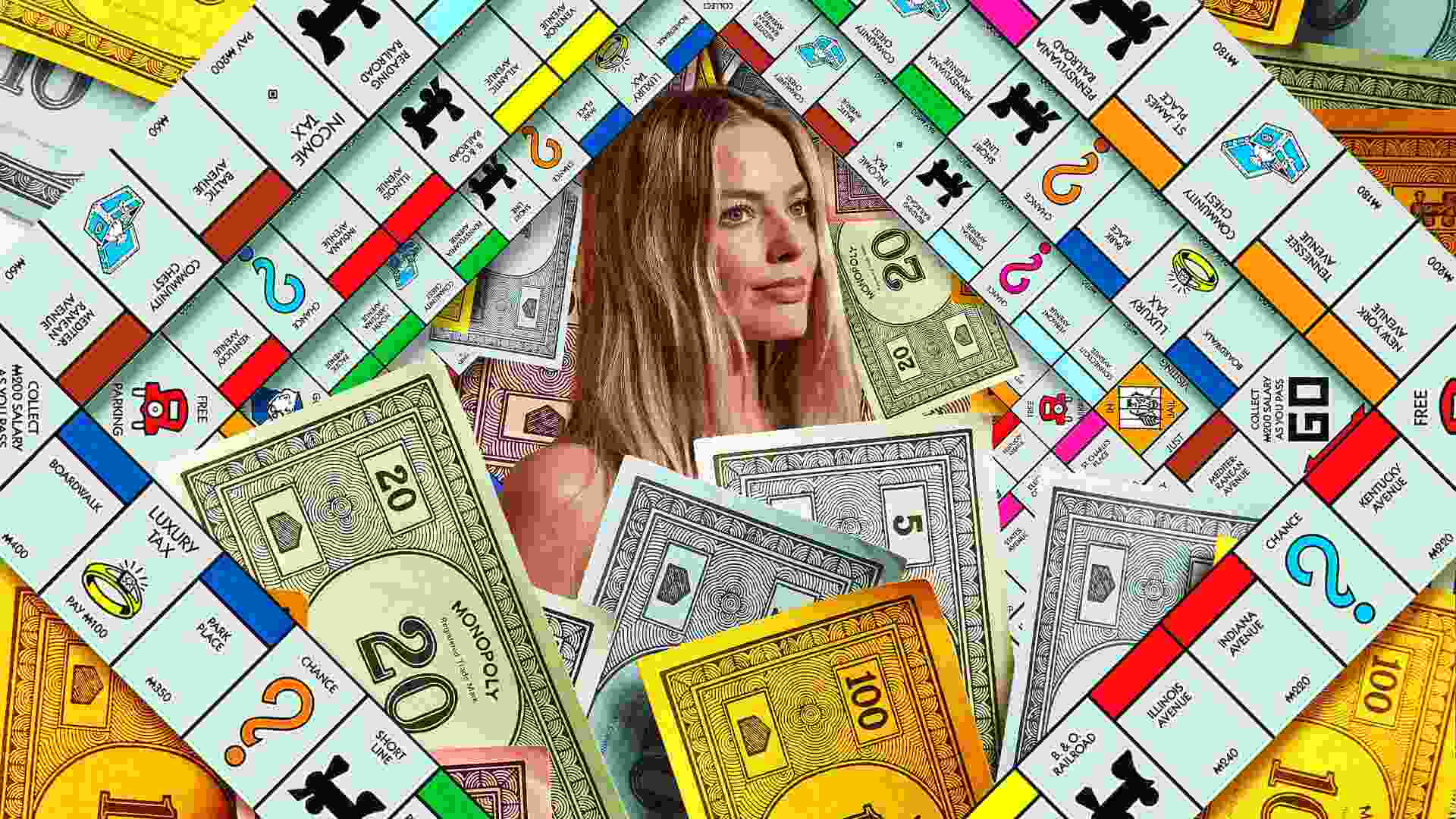

By now, we’re all familiar with some version of the statistic that consumers ages 55 and over are growing in number and control 70% of our country’s wealth. That’s correct, a clear fact. We’re also all familiar with—and perhaps adherent to—a blanket assumption that older generations neither want nor understand technology. By contrast, that is a gross misconception; one that we in the tech industry are far overdue in addressing.

Before becoming a founder in the senior tech space, I spent over a decade working on “regular” tech products—most of which were geared toward twenty- and thirtysomethings. In fact, it was that front row seat to the age bias in tech that eventually led to my passion for developing tech innovation to serve adults 55 and over. As someone not in the demographic that my company targets, I’ve had to learn about our consumer the old-fashioned way—with user research, lots of conversations, and more than a few missteps. Now, nearly two years into building product for an older demographic, here are a few key things I’ve learned along the way about designing for our aging population:

Put the people—not the aging—first.

Too often, we tech folk have shorthanded usability for older adults by simply increasing font size and designing for iPad legibility.

I learned early that one of the best (meaning: worst) ways to belittle our user was to go into design thinking, “this is for someone over 55.”

One: Even if the U.S. Census and media brackets do still batch everyone over 55 or 65 into one single age range, in reality it’s about as far from a homogeneous group as you can get.

Two—and perhaps more importantly—that thinking, and its resulting designs, aren’t reflective of how that demographic sees themselves. No one wakes up in the morning and thinks, “It’s Saturday, I’m 60, what should I do today?” (Arguably, no one of any age does that—so why do we treat “senior” as a defining characteristic?)

As designers and product managers, we have to design for how our users define themselves—which, for this demographic, is almost never in an age-first way. This same idea applies to branding and communication elements like headlines and imagery: For example, we never use the word “senior” because it’s a mismatch with how our users describe themselves—instead, based on what we’ve heard from our consumers and our team members, we say “older adults.”

We also take special care with imagery—stock photos of this age group are full of these hazy, backlit, “golden years” kind of shots of people with gray hair walking in the park. This drives our team members, who are actually in this demo, crazy—it’s just so far off of how they actually live their lives and spend their time—doing activities, having coffee, visiting friends . . . all in normal lighting.

Which brings me to the fact that the so-called tech illiteracy of older generations is a fallacy.

Just think about it: People 50 and over were actually the first generations to adopt tech—they bought the first cell phones, mastered Pong, played the first Ataris, and Nintendos. The fact that these generations didn’t grow up as digital natives doesn’t mean they’re digitally inept or uninterested.

Instead, what the tech industry writes off as “tech incompetency” is more often than not a question of habit and training.

Take what’s commonly known as the “hamburger menu” as an example. Twentysomethings who grew up with phones in their hands have been trained—for years—to know that those three lines on a mobile website are an expandable menu. But older users, who may be newer to using mobile for browsing, don’t necessarily know that same design language—not because they’re dense, but because they don’t have those same years of training.

Instead of writing that off as incompetence, why not think about it as a design and training problem? How might we create designs and educational tools so that we’re bringing older demographics along with our design signals? How can we actually design products that this demographic tells us they want, instead of retrofitting designs for twentysomethings for an entirely different target market?

Finally: Think equally hard about the design of your team.

As a product manager at places like Zynga and ClassPass, a rule of thumb was to “design for ourselves.” That’s common in many tech environments, in which the average age of workers (35) more or less matches that of the user target.

But now that I’m building for someone whose age doesn’t match my own, that guideline no longer applies: I’m no longer personally a user of the product I’m designing, which means I can rely less on intuition and gut. Targeting a demographic different from my own has pushed me and my team to lean harder on design and marketing best practices—we do usability testing, talk to our consumers, prioritize elegant and simple design. When I was first thinking about the Hank concept, for example, I didn’t start to build anything right away, like I might have at other companies. Instead, I booked myself on a seven-day cruise to the Bahamas and spent the trip pitching the concept to cruise participants within the Hank demo. In exchange for their feedback, I would hand out dozens of Amazon gift cards. In some ways, I’ve found that being outside of our target demo makes the product easier to “get right”—because we, by necessity, have to remove our personal biases and assumptions from what we’re building.

What that also means is that I’ve hired a more senior team than most other tech organizations I’ve seen in the past. That’s not necessarily an effort to get us closer to our target demo’s age; it’s more a reflection of needing people who have the training to understand and implement those best practices rather than using our gut to get us halfway there.

In hiring folks that understand our user’s mindset, needs, and position, tech teams can better step out of an echo chamber of developing products for 20- to 30-year-olds. The 55 and over populations have been overlooked and misunderstood for too long by the tech industry, and they deserve some truly dashing product.