- | 7:00 am

Oatly’s climate-footprint counts are a sign that carbon labels are going mainstream. Do they work?

Unlike nutrition labels, climate claims on packaging are unregulated. And there’s no consensus yet for vetting them.

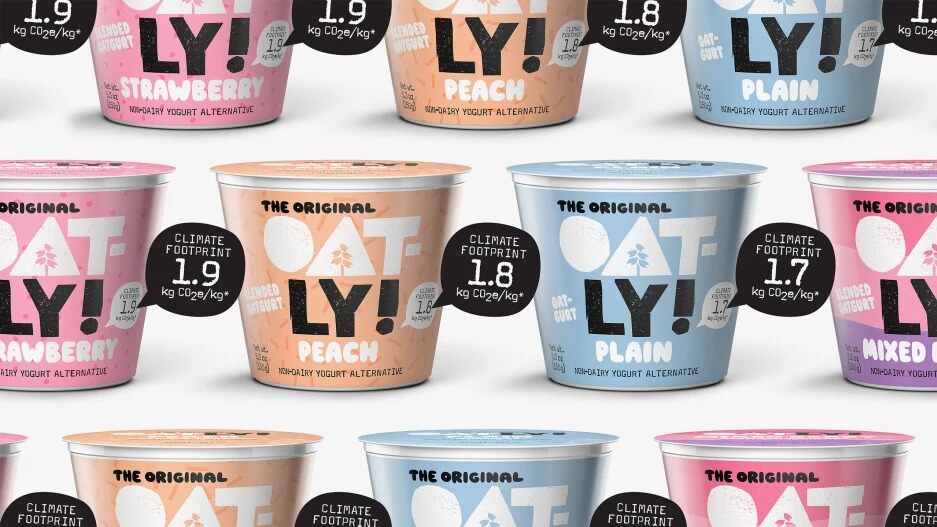

Oatly announced that it has added climate-footprint labels to some of its plant-based dairy alternatives on U.S. shelves, a first for a major food brand.

Four of its so-called Oatgurts are now carrying an eco-label intended to help consumers “compare the climate impact of different products right in the grocery aisle . . . the same way they can see the labeling of fat, sugar, and other nutritional information.” Oatly says it plans to add the label to 12 more products by 2025, including its popular oatmilks and more obscure items, such as its line of Dipped Bars. In the meantime, the climate impacts of all 16 products can be seen online at oatly.com/footprint.

Our food system produces about a third of all climate-worsening greenhouse gasses. Beef and other meats are the category’s worst—1 kilogram of beef is responsible for nearly 60 kilograms (or about 132 pounds) of carbon-dioxide equivalent, or CO2e, according to a recent Carbon Brief analysis. Yet dairy could also do better: It produces 3.15 kilograms (or, nearly 7 pounds), while nuts average 0.43 kilograms (less than 1 pound), and oatmilk produces 0.9 kilograms (nearly 2 pounds).

Dairy may be trying to clean up its act (research shows that between 2007 and 2017, producers reduced emissions by 19%, alongside land and water use too), but Oatly’s 16 products range from 0.6 kilograms (for plain oatmilk) to 1.9 kilograms (for the strawberry and mixed-berry Oatgurts, and the chocolate fudge Dipped Bar).

ALREADY A TREND IN EUROPE

Since 2021, the Swedish company has been printing climate labels on products sold in Europe, where eco-labeling has picked up more steam. But that makes it a pioneering move for a food company in America, one that could annoy the segment of shoppers who tell surveys that they believe these plant-based food brands are too “woke.” Adding a prominent label invoking kilograms of CO2e onto a package that already contains labels that read “Non GMO Project verified,” “Certified vegan,” Certified gluten free,” and “Glyphosate residue free” primes Oatly for anti-ESG pushback, though presumably the brand’s customer base is less put off by climate-footprint disclosures on packaging.

Verifying the claims behind the labels, though, is where ESG’s proponents might start asking questions. A dizzying array of nonprofits and companies promising to help clients calculate and reduce their footprints has materialized, and there are reasons to doubt the standards of several, all while shoppers struggle to vet them on the fly. Just this month, a team of European media outlets published a nine-month investigation claiming that over 90% of carbon-offset credits offered by Verra—the world’s top certifier—were “phantom credits” that “do not represent genuine carbon reductions.”

Oatly seems to have anticipated suspicious consumers, at least partly. Its webpage for the labels explains: “We decided to go ahead and declare the climate footprint of our products in the most transparent and complete way we think is currently possible,” meaning as kilograms of CO2e per kilogram of product, “then share more information about the calculations on this webpage.”

It selected CarbonCloud, a climate-modeling company, to audit measurements. Spun out of research at Sweden’s Chalmers University of Technology, CarbonCloud has done assessments for dozens of brands, among them the fruit giant Dole, Danish food company Naturli, and baby food maker Little Freddie. Its model has been used by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and Princeton University.

“They’ve been a valued partner of ours since we first introduced product climate footprints for many of Oatly’s European products in 2020,” Oatly North America’s sustainability director Julie Kunen tells Fast Company, describing it as a collaboration with CarbonCloud’s platform “supporting the work of our in-house lifecycle assessment specialists.”

The two companies conduct a life-cycle assessment to capture all emissions along the supply chain—up to those associated with the end consumer’s usage and disposal, a metric more companies have started adding. Total emissions are translated into the kilograms of CO2e number that Oatly is printing on packages. Oatly provides consumers a link to dive deeper into CarbonCloud’s methodology. Under the nutrition facts label on the backside, it provides additional information, including the measurement’s date of certification.

There is, though, one big difference between climate labels and nutrition facts labels: The latter are carefully controlled by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States. Climate claims mirror other unregulated claims like “all-natural” or “free range”—there’s no consensus yet for determining if products are what they say they are, or even for how to print the data on packages.

Maybe that will be arriving soon, but until then, Oatly argues it’s trying to help. “Until standardization and a mandate become reality, Oatly wants to encourage other companies in the food industry to put their CO2e figures on their packaging,” the company says, noting that until other companies join, it will remain tough for consumers to make “an apples-to-apples comparison.”