- | 10:30 am

You next flight might land differently because of climate change

But you won’t even notice.

If you fly into Atlanta or Phoenix or Seattle, you likely won’t notice any difference in how your plane lands. But for the past several years, the FAA has been working with airports to roll out a change that helps cut emissions.

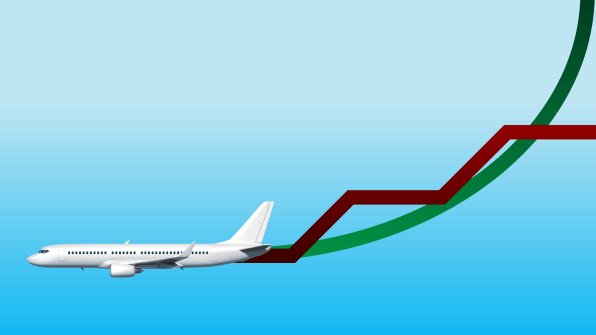

In the past, planes always used a “stairstep” procedure as they descended, repeatedly leveling off and coordinating with air traffic controllers at each step to avoid any conflicts with planes landing on nearby runways. Now, they’re able to descend in a smooth, continuous path, which makes it possible to save fuel and cut emissions on each flight.

It’s one example of an invisible change that can help chip away at the industry’s massive carbon footprint before bigger shifts—like sustainable aviation fuel made from captured CO2 or new technology like hydrogen-powered planes—can happen.

GPS technology now allows planes to precisely follow a specific path and keep their engines near idle as they glide down. “It follows a series of those waypoints, those navigational positions, and we can also optimize for height,” says Paul Fontaine, head of the agency’s NextGen program, which is modernizing airports in the U.S. “When we optimize for height, we can get that kind of gentle, powered-down approach right down to the runway.” In the past, as planes descended in stages, they’d burn their engines at each step, using more fuel. It also required more work from air traffic controllers and meant that airports could accommodate fewer planes at a time; now the process is more automated.

The FAA started working with some airports to enable the new approach, called “optimized profile descents,” in 2014, and announced today that it rolled out at several more locations in 2022, including airports in Orlando, Reno, and Kansas City. In total, more than 60 airports have implemented it. In each case, it takes a year or two of work to plan the routes that planes can take before the change can take place; in a metro area with multiple airports, it can mean coordinating as many as 60 or 70 different simultaneous approaches. More airports will be added, though the agency doesn’t have a plan yet to implement it everywhere.

In a year, the airports where the new procedure is now in place can eliminate around 600,000 metric tons of emissions a year. That’s still a tiny fraction of the airline industry’s total impact—globally, aviation emitted around a billion metric tons a year before the pandemic. But it’s part of a suite of small changes that can make a difference.