- | 9:00 am

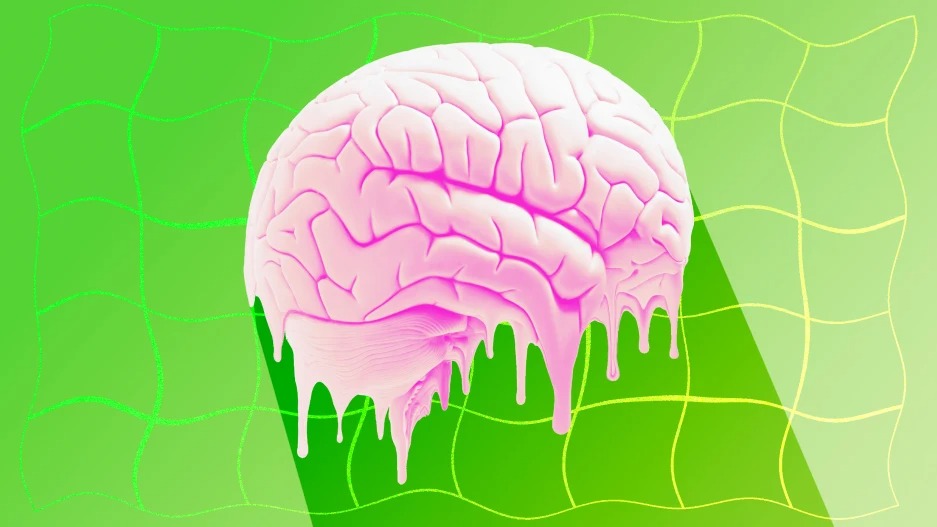

How AI is making us more boring and less creative

In this excerpt from I, Human, the author argues that it is up to us to develop and grow our real selves, beyond the predictable creatures co-opted by AI.

Although AI has been rightly labeled a prediction machine, the most striking aspect of the AI age is that it is turning us humans into predictable machines.

When it comes to our everyday lives, algorithms have become more predictive because the AI age has confined our everyday lives to repetitive automaton-like behaviors. Press here, look there, drag down or up, focus and un-focus—repeat. By construing and constraining our range of behaviors, we have advanced the predictive accuracy of AI and reduced our complexity as a species.

Oddly, this critical aspect of AI has been largely overlooked: It has reduced the variety, richness, and range of our psychological experience to a rather limited repertoire of seemingly mindless, dull, and repetitive activities, such as staring at ourselves on a screen all day, telling work colleagues that they are on mute, or selecting the right emoji for our neighbor’s funny cat pictures, all in the interest of allowing AI to predict us better.

As if it weren’t enough to enhance the value of AI and Big Tech through our nonstop training of the algorithms, we are reducing the value (and meaning) of our own experience and existence by eliminating much of the intellectual complexity and creative depth that has historically characterized us.

HUMANITY AS AI’S SELF-FULFILLING PREDICTION

When the algorithms treat or process the very data we use to make practical and consequential decisions and life choices, AI is not just predicting but also impacting our behavior, changing the way we act.

Some of the data-driven changes AI inflicts upon our life may seem trivial, like when you buy a book you’ll never read or subscribe to a TV channel you never watch, while others can be life-changing, like when you swipe right on your future spouse. Most of us know of marriages that started (or ended) with Tinder, with research suggesting that more long-term relationships form via online dating than any other means.

Along those lines, when we use Waze to work out how to get from A to B, check the weather app before we get dressed, or use Vivino to crowdsource a wine rating, we are asking AI to act as our life concierge, reducing our need to think while attempting to increase our satisfaction with our choices.

Having trouble coming up with a new password? Don’t worry, it will be auto-generated for you. Don’t feel like finishing a sentence on email? All good, it will be written for you. And if you don’t particularly feel like studying the map of a city you are visiting, learning the words of a foreign language, or observing the weather patterns, you can always rely on technology to do the job for you. Just as there’s no need to learn and memorize people’s phone numbers anymore, you can get by in any remote and novel destination by following Google Maps. Auto-translate AI will help you copy and paste any message to anyone in any language you want, or translate any language to yours, so why bother learning one? And, of course, the only way to avoid spending more time picking a movie than actually watching it is to follow the first thing Netflix recommends.

In this way, AI absolves us from the mental pain caused by having too many choices—something researchers call the choice paradox. With greater choice comes a greater inability to choose or be satisfied with our choices, and AI is largely an attempt to minimize complexities by making the choices for us. NYU professor and author of Post Corona Scott Galloway noted that what consumers want is not actually more choice but rather confidence in their choices. And the more choices you have, the less confident you will logically be in your ability to make the right choice. It seems that Henry Ford was exercising a strong form of customer-centricity when he famously stated that “customers are free to pick their car in any color, so long as it is black.”

Regardless of how AI unfolds, it will probably continue to take more effort out of our choices. A future in which we ask chatGPT what we should study, where we should work, or who we should marry is by no means far-fetched. In fact, the enthusiasm generated by this conversational user interface is testimony to our desire to outsource as much of our thinking to machines, without necessarily planning to redeploy our intellectual resources on some creative or valuable activities.

Needless to say, humans don’t have a brilliant track record at any of these choices, not least because historically we’ve approached such decisions in a serendipitous and impulsive way. So, much as in other areas of human behavior that become the target of AI automation—for example, autonomous vehicles, video interview bots, and jury decisions—the current bar is low.

AI does not need to be too precise, let alone perfect, to provide value over average or typical human behaviors. In the case of self-driving cars, this would simply mean reducing the 1.35 million people who die in car accidents each year. In the case of video interview bots, the goal would be to account for more than the 9% of variability in future job performance that traditional job interviews account for (correlation of 0.3 at best). And in the case of jury decisions, it would simply require us to reduce the current 25% probability that juries have to wrongly convict an innocent person—that’s nearly three in ten defendants.

Thus, rather than worrying about the benefits of AI for effectively taking care of decisions that historically relied purely on our own thinking, we should perhaps wonder what exactly we are doing with the thinking time AI frees up. If AI frees us from boring, trivial, and even difficult decision-making, what do we do with this gained mental freedom? This was, after all, always the promise and hope of any technological revolution—standardize, automate, and outsource tasks to machines, so that we can engage in higher-level intellectual or creative activities.

However, when what is automated is our thinking, our decision-making, and even our key life choices, what are we supposed to think about? There is not much evidence that the rise of AI has been leveraged in some way to elevate our curiosity or intellectual development, or that we are becoming any wiser. Our lives seem not just predicted, but also dictated by AI. We live constrained by the algorithms that script our everyday moves, and we feel increasingly empty without them. You can’t blame technology for trying to automate us, but we can, and should, blame ourselves for allowing it to squeeze any creativity, inventiveness, and ingenuity out of us just to turn us into more predictable creatures.

The problem is that we may be missing out on the chance to infuse some spark, richness, and randomness—not to mention humanity—into our lives. While we optimize our lives for AI, we dilute the breadth and depth of our experience as humans. AI has brought us too much optimization at the expense of improvisation. We appear to have surrendered our humanity to the algorithms, like a digital version of Stockholm syndrome. Our very identity and existence have been collapsed to the categories machines use to understand and predict our behavior, our whole character reduced to the things AI predicts about us.

Perhaps in the not so distant future we will take pleasure in “fooling AI” by reducing the accuracy of its predictions, recommendations, and nudges, arbitrarily liking and sharing content we don’t like, to distort its view of ourselves. This would be akin to living a secret and parallel life where we can just be ourselves, or unleash our private, hidden identity, far away from the matrix and the metaverse. They can have our deepfakes but it is up to us to develop and grow our real selves, beyond the predictable creatures co-opted by AI.

This is an excerpt from I, Human: AI, Automation, and the Quest to Reclaim What Makes Us Unique published by Harvard Business Review Press and is reprinted with permission.