- | 8:00 am

How Margrethe Vestager got the upper hand over Big Tech

The two landmark pieces of legislation she ushered through European Parliament this year, the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act, are having ripple effects around the world—and finally forcing Big Tech companies to take responsibility for their actions.

While many businesses floundered during the pandemic, Big Tech thrived. Even as markets have entered bear market territory, large technology companies—including Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta Platforms, and Alphabet—still account for nearly 20% of the S&P 500, a weighted index of the largest public players in the U.S. But stock market indices don’t begin to capture Big Tech’s influence—over culture, speech, business formation, and even democracy. And no one person is doing more to compel technology companies to take responsibility for their power than Margrethe Vestager, a Danish politician who has served as Europe’s commissioner for competition since 2014.

Vestager first made international headlines in 2016 for handing Apple a $14.5 billion tax bill, arguing that the tax breaks it had been granted by Ireland constituted an illegal subsidy. While the decision in that case was overturned, Vestager has not slowed down. In fact, her mixed record in using the courts to stop anticompetitive behavior is what motivated the ambitious double whammy of a legislative agenda that she successfully shepherded through Europe’s legislative chambers this past spring. The Digital Markets Act identifies market-controlling “gatekeepers” and threatens them with serious punishment for self-dealing behavior, while the Digital Services Act takes aim at social media by addressing areas such as ad targeting and misinformation. Big Tech spent roughly $30 million to lobby against the E.U. laws in 2021, and has so far spent more than $36 million on an ad campaign designed to undermine proposed U.S. antitrust legislation that echoes Europe’s.

But Vestager has the momentum. Already, lawmakers in countries including Australia, Japan, Nigeria, and South Korea are following in her footsteps. In the midst of confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson in early April, Senator Amy Klobuchar, chair of the Senate committee overseeing competition policy, made time for an in-person meeting with Vestager in Washington, D.C.

Prior attempts at tech regulation have taken a piecemeal, case-by-case approach. Vestager’s sweeping legislative victory marks a fundamental reckoning: Do our digital lives reflect our values? Her blueprint for regulation is designed to offer a path to “yes.” Vestager connected with Fast Company in late May to discuss her creative approach to regulation. What follows is an edited version of the conversation.

Are you in Brussels for the whole week, or will you be going to Davos?

No, I don’t go to Davos.

That’s probably a good thing.

Well, as a competition law enforcer, I find it inappropriate. Because from what I have heard, everyone is getting a bit cozy. Most important discussions can be had in other places, where it’s more transparent.

It’s very hard to be the law enforcer at a cocktail party.

Exactly, exactly. That’s my thinking. That being said, I think it’s important that there are fora where people can discuss the state of the world. I just find it more interesting if it’s a more mixed audience. I think they’ve been working on that, to try to make it a bit broader.

Well, maybe they’ll change the world there this year.

Don’t hold your breath.

There’s been a shift in thinking about antitrust. In the U.S., we are taking a more expansive view of consumers and how they’re affected by competition. Are you bringing a similar lens to your oversight of Europe’s digital markets?

Over the last few years we’ve seen more and more that innovation plays a role when it comes to competition. So we have price, choice, quality, [and] innovation. One should not be negligent about price because, especially in these days with higher inflation, affordable products are really crucial for many families. But what we increasingly have been looking for is if innovation is being disturbed by, for instance, a merger, or unfair trading practices, or a behavior in the market that would add up to misuse of a dominant position.

How does the sheer size of the Big Tech companies play into this? Thus far, the legal fees and fines these companies have incurred from managing lawsuits are so small, relatively.

That is part of the rationale for regulation. To say that we need to do more. We will keep on vigilantly enforcing competition law case by case; but we see that this is not enough because there is very little learning from the cases. We did what we call a sector inquiry into the consumer internet of things, and we saw all the practices that we had been punishing in previous cases. We have nothing against success. But with success comes responsibility.

Let’s talk about the Digital Markets Act, with this idea of gatekeepers. It feels really different to say “gatekeeper” than “monopolist.” How did you choose that language?

It’s a metaphor. But we find that it’s appropriate because it is almost literally as if someone is keeping the gates into the marketplace. If you’re an investor, and you want to invest in a smaller company, it’s not their idea or their work ethic or the rest of the funding they have that will make sure that they can get to market. It is whether or not they can pass the gate. So if they depend on a gatekeeper to go to that market, you may be more reluctant to invest in them.

What we have done is we have translated all the characteristics of being dominant in the market into the criteria for what then shapes a gatekeeper. What we want, with all the obligations and all the things that you will have to do if you are designated a gatekeeper, is for that gate to stay open. It is crucial for any economy that the market is open and contestable; that it is fair.

Let’s take app stores, for example. How will the legislation affect how companies manage their app stores—and new, unofficial app stores that will need to be present on their platforms and devices?

The [idea] that you only have one place to go for your shopping is really, really strange. The thing is that, once you buy a phone, it’s not easy to say, well, no, I don’t like the app store on my phone, so I will now discard this phone and buy another phone to be able to go to another app store. It would be the same if you had to move from the city where you lived to another city in order to find another supermarket. We’d find that crazy. If you, as a consumer, choose to have another app store on your phone, it may come with different qualities. It may be that it’s specialized, a gaming app store. It could offer different forms of payment than other app stores.

The argument that I often hear a company like Apple put forward against this is that there’s a choice that has to be made between competition and security.

I think it’s a false contradiction. You can have choice and safety. Second, I bought a phone, but do I need Apple to mother me?

Probably not.

No. Also, you will have a right to disable and get rid of apps that you don’t want. Most people like the out-of-the-box experience. I can start using my phone immediately. But maybe I don’t want some of the preinstalled apps. That’s not possible today. So just to be able to say, I love this phone. I love every feature of it, but I don’t like the apps that they have made for me. I want my own. I want to make choices. I’m an adult.

One thing that seems to define Big Tech companies is this idea that it’s the data that makes them powerful. Does that make these companies unique and therefore uniquely challenging to regulate?

It’s always about people. There’s always someone somewhere who has [made] a business decision. It’s not neutral. It’s not the algorithm. It’s not naturally grown. Data is something that humans create when interacting. So I think a lot comes from the fact that a group, a generation of people, saw the possibilities and ventured into this. They were willing to say, “Well, this is what we want to do.” If [Facebook whistleblower] Frances Haugen is right, then they were also willing to do things that are potentially damaging to other people in order to make better use of the technology. That’s a human decision.

I know you met with Haugen recently. How have conversations like that affected your thinking?

I’m not against a certain company. It’s my task to make sure that the behavior of a company, and especially such a big company, is enabling a fair and contestable market. What I have seen is that that has become increasingly challenging, because [these big companies] don’t change that behavior fundamentally. We see it over and over again. And not only that, despite codes of conduct, we see, [for example,] the Facebook Cambridge Analytica scandal. In order to make full use of what technology can give us in terms of enabling better societies, we really, really have an urgent task to get in control of the more destructive sites.

It seems like both the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act are an attempt to get ahead of this. Because it does feel like the companies have done a very good job, in the U.S. at least, of trying to front-run the problem and craft their own solutions, through oversight boards and the like. That self-regulation has, in many cases, quashed the legislative momentum that we might otherwise have seen, at least in Congress.

Part of the problem with self-regulation is that it’s business by business. And the second thing that I find makes me smile a bit is that now they have all been asking for regulation. Only never the regulation that we have proposed. It seems there’s always something else. It’s about time that democracy moves back in. It’s about time that our representatives march back in, and say, “Well, we are trusted to make sure that the world is working, no matter if it’s an analog or a digital part of it.” The timing could not be better because we are entering into this new phase of digitization where a modern tractor or agricultural machinery, it will take satellite data, it will analyze the soil that you’re driving on. It will be able to give advice to the farmer as to the density of sowing, or how to use the fertilizer, and to what degree, depending on humidity. With this sort of industrialization of digital, we really need a more open, transparent, predictable, regulated space where the benefits are somewhat distributed.

In announcing the passing of the Digital Services Act, you noted that it had evolved since you started working on it two years ago. How was the act strengthened, and why?

One feature, like the de facto ban of targeted advertising for minors—that’s a good thing [that we added]. Also interoperability [between platforms like iOS and Android], starting with text messaging, and then moving to video messaging. Then the combination of data—[enabling] adults to choose whether we want targeted advertising or non-targeted advertising, to say that there are some kinds of sensitive data about who I am that cannot be combined with behavioral data for advertising purposes. I think this is good because it makes it obvious that there are choices.

I’ve heard you talk in the past about some of your own digital habits—for example, you avoid shopping on Amazon. Is that still true?

That is still true. I’m not really successful with my family, I can tell you.

No one is responsible for their family members.

Well, but one can preach a bit, I’d say. But always with limits.

One of my colleagues wrote a story about what happened when she tried to cut Amazon out of her life entirely. Essentially, it was impossible. Even when she was trying to shop elsewhere, perhaps Amazon was doing the fulfillment, or running the website in some way.

It’s one of the reasons why it’s tricky to have a nonGoogle life: A lot of websites use Google Analytics. So even if you don’t have a Gmail, or a subscription to Google services, your data will still somehow get to Google. It’s good if you can actually make that choice, go into the settings to say, “Thank you, but no thank you. I don’t want to provide my data for this.”

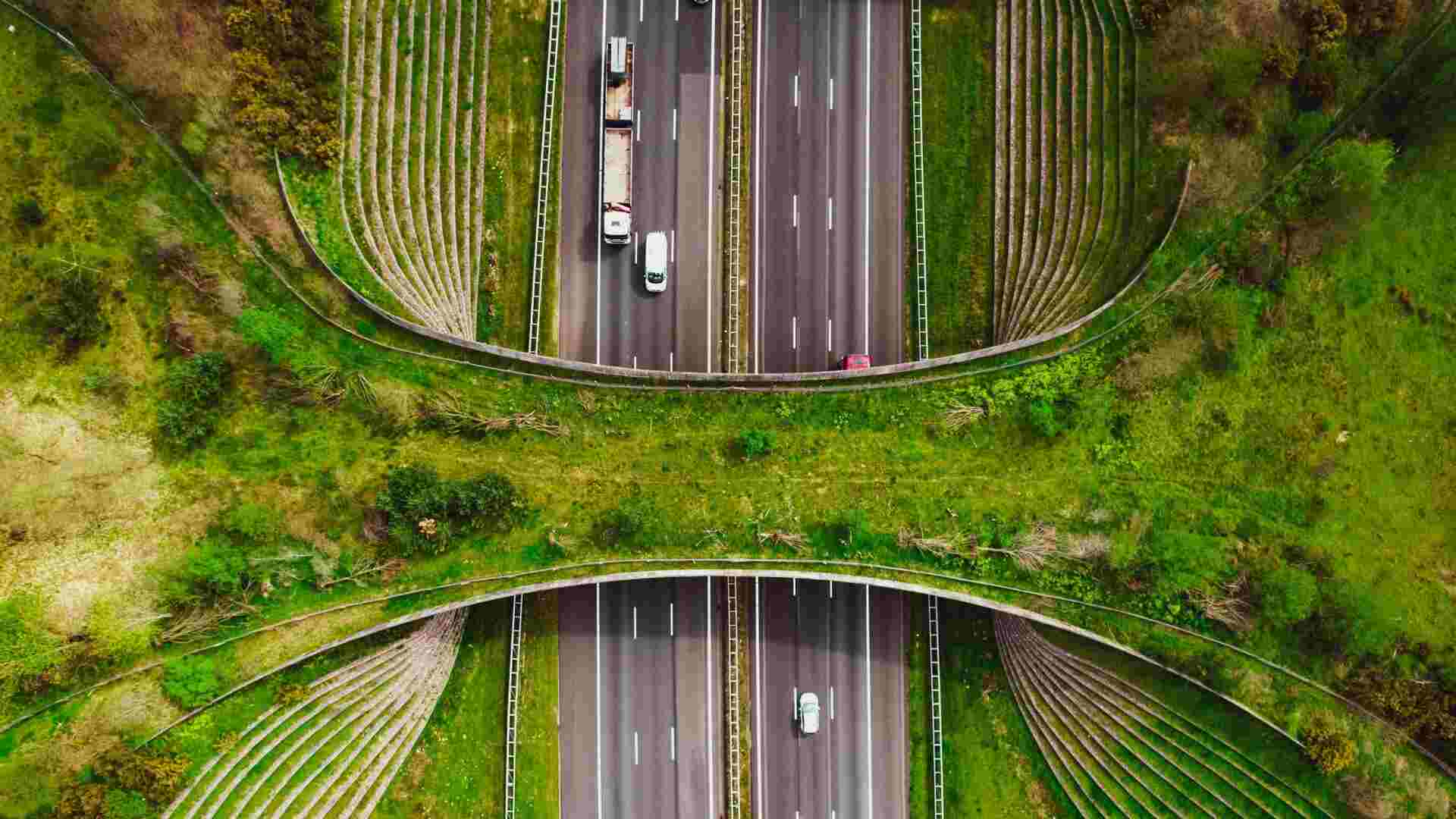

On your question of Amazon, what is important is that you have competition in all the different parts of this integrated value chain. For instance, in delivery and transport. We need that competitive spirit for innovation to continue because we have not seen the last way things are delivered. Probably they will be delivered in many more innovative ways in the future.

There’s a piece in the Digital Services Act focused on the question of speech on platforms. When Elon Musk launched his takeover bid for Twitter, it initiated a larger conversation about how Twitter thinks about free speech. Do you think a more expansive definition of acceptable speech is in conflict with the legislation?

Well, myself, I’ve been really appreciating the changes that Twitter has made over the last couple of years, that you’re reading a tweet about using bleach as a COVID remedy, that there is also a reminder that you can go here for official information about COVID. Or, if I want to retweet a commission press release, where I myself am credited, Twitter would say, “Don’t you want to read it before you retweet it?”

They always ask me. And yes, I read it. I wrote the article!

Exactly. But I think these are good suggestions. Speed is not the essence here. The more important thing is that if Twitter continues to be offered as a service in Europe, it will have to live up to the Digital Services Act. If there is a risk that a service can be used to undermine democracy, the service will have to be assessed, the risk will have to be mitigated. If there are posts that are suspected or seen as being hate speech, or incitement of violence, they have to be taken down. There must be this system where people can complain about it. Any owner can have ideas about the business, how they want to develop it. But once the legislature has said, “This is the framework,” you have to live up to that.

Russia is trying to create its own tech ecosystem. China, too. On the other hand, we have companies like Facebook where it feels sort of strange, in a way, to call them American because they are so global. Do these geopolitical shifts make your job more challenging?

Globalization has changed forever, [and that change] definitely accelerated with war coming back to Europe. Ukraine is the first fully digitalized war because everyone has a phone with a camera to document war crimes, to document damages, to stay in touch. But there is a positive trend, at least from my point of view, in a globalization where we qualify what it is that we want. [We want to fight] climate change, [we] want everyone to respect the International Labor Organization’s workers’ conventions. What is important is that the internet remains global. What happens then to the services provided via the internet, that may have its ups and downs.

It seems like we’re in a new phase right now, where society is focusing on how values can and should intersect with the digital economy. In the U.S., at least, for a long time the tech world has been tied to a libertarian ethos, where it’s just about the government steering clear of a future tech utopia.

That was for the few, the 1%. Because the rest were supposed to be data points, lulled into convenience. And convenience kills curiosity. So you’re just a data point. Then you have the 1% who can say, “Well, we are the ones who benefit from all of this, and we don’t need the state. We don’t need any of those old-school values.” The only reassuring thing now with war in Europe is that it is so clear that we have things to fight for. And they are real. That can break the lull of convenience and say, “We want to change how things are working.”