- | 8:00 am

Humane’s ambient computing vision is a dead end

The biggest barriers to a post-phone era have little to do with AI.

Humane seemed to anticipate that the first reviews of its AI Pin would be brutal.

In an interview with Inverse and a statement to The Verge, Humane’s cofounders positioned the AI Pin not as a finished product, but as the start of an “ambient computing” era. The idea is that technology will recede into the background, and our smartphones will be supplanted by all-knowing virtual assistants that are just a voice command or gesture away.

It’s a tantalizing vision for anyone who’s watched an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, but we already know it’s impractical. Bigger companies such as Google and Amazon spent years trying to deliver ambient computing, and they’ve failed for reasons that have nothing to do with AI shortcomings or hardware limitations. The whole concept is simply at odds with how the tech industry works, and it’ll forever be held back by a lack of cooperation and limited profit potential.

WE’VE BEEN HERE BEFORE

Combined, Amazon and Google have shipped tens of millions of smart speakers, and they’ve loaded their respective Alexa and Google Assistant on myriad other devices, including TVs, streaming boxes, smart displays, and even thermostats. Both companies have also used the terms “ambient computing” or “ambient intelligence” to describe how their assistants will usher in a kind of post-phone era.

“The technology just fades into the background when you don’t need it. So the devices aren’t the center of the system, you are. That’s our vision for ambient computing,” Rich Osterloh, Google’s head of devices and services, said at the company’s I/O conference in 2019.

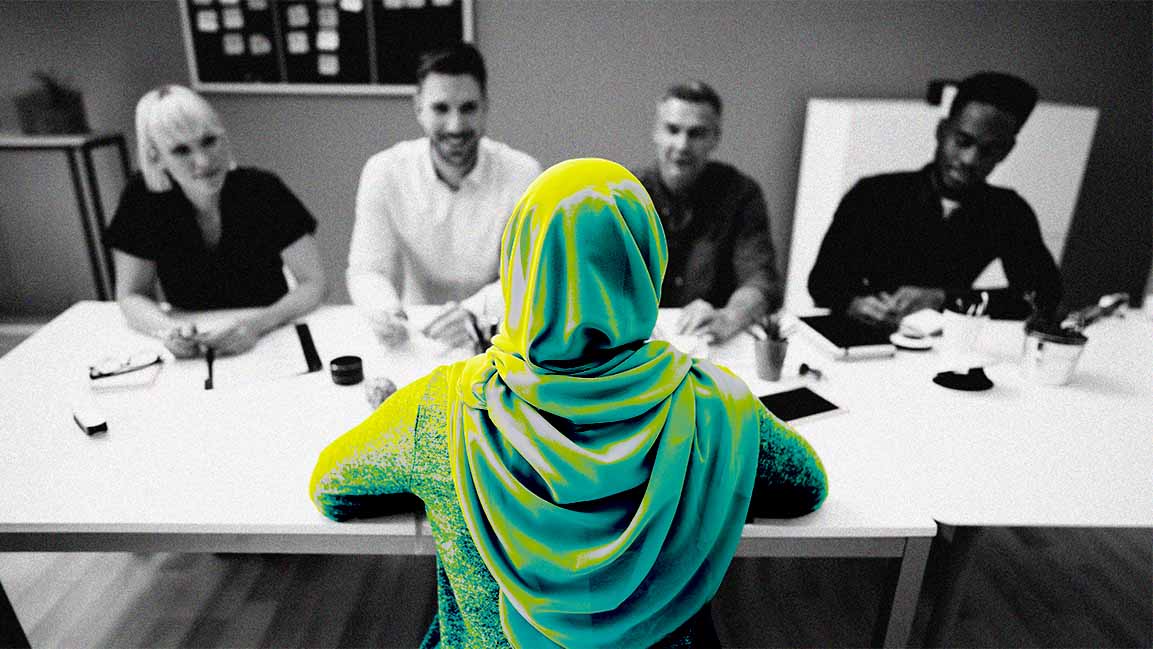

But while ambient computing hardware is now pervasive, the lofty goal of intelligent assistance hasn’t materialized. That’s largely because getting these assistants to interact with the surrounding world is a thankless slog that requires not just better AI, but links to an impossibly broad array of warring ecosystems.

For example, let’s say you want to play something on the TV with a voice command. Both Alexa and Google Assistant support this in theory, but only with a precise combination of hardware and software. You need a speaker with the right voice assistant, plus a TV that’s compatible with commands from that assistant. Even then, it might not work because the streaming service you want to watch doesn’t work with the voice assistant you selected.

So, we end up with situations where you can only ask a Google speaker to watch ESPN on your Google TV if you get ESPN via YouTube TV (which is owned by Google) instead of Hulu (which is owned by Disney). And if you want to watch YouTube videos on your Echo Show display, it’s not possible without elaborate workarounds.

TV is just one example, but think of all the other things that ambient computing can’t do. You can’t ask Alexa to check your Slack messages or get a summary of missed social media notifications. You can’t pull up your email on the nearest TV or smart display, nor can you review a Notion page or Google Doc. You can probably play music, but good luck transferring playback from one device to another unless they’re all part of the same whole-home audio system.

Humane has already gotten a taste of this with its AI Pin: The only streaming music service it works with is Tidal, and it only connects to external speakers via Bluetooth. It’s unclear which other music service the AI Pin will support in the future, or if you’ll ever be able to cast audio to TVs and smart speakers.

WHERE’S THE MONEY?

The underlying problem for ambient computing—one that may explain the issues above—is the lack of money to be made from it.

Amazon and Google both sold their smart speakers with slim profit margins—and even reportedly at cost, in Amazon’s case—with hopes of building market share and finding profitable use cases over time. Those attempts to monetize have largely failed.

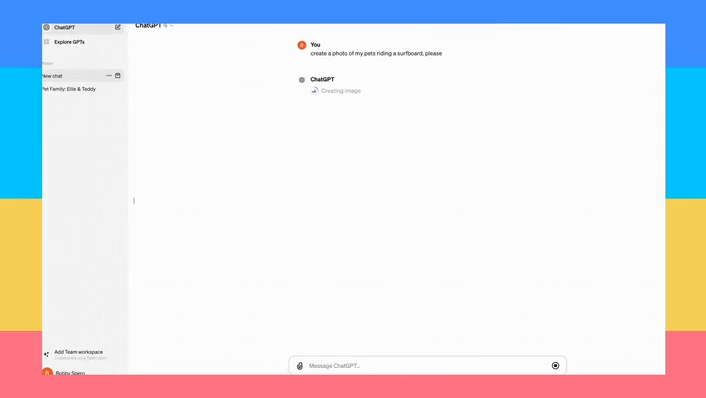

Neither Amazon nor Google ever resorted to sticking ads into their voice interactions, rightly figuring that users would revolt. (Even Amazon’s attempts to advertise other useful things you can do with Alexa haven’t gone over well.) Assistants driven by large language models will run into the same issues, which is why generative AI firms are now tiptoeing around the idea of advertising in their own products.

Meanwhile, a report by Business Insider found that financial gain from Alexa voice shopping “fell short of expectations,” and partnerships with Uber and Dominos for voice-based ordering “failed to generate engagement.” Developers have long complained about how little money could be made from third-party Alexa skills, and now Amazon appears to be backing away from that ecosystem. Earlier this month, it discontinued its free Amazon Web Services credits for hosting Alexa skills and its rewards program for top developers.

Will generative AI make third-party apps and skills more feasible? Debatable, given that AI plugins have been largely useless so far. But either way, ambient computing is not going to make someone order more pizza or call for more Ubers than they otherwise would with an app on their phone. The incentive to build out and support these systems will be limited regardless of whether large language models are up for the task.

The same could be said of the ambient computing platforms themselves. Even before Google’s big generative AI push, users had been complaining about a perceived decline in quality for Google Assistant, even for basic queries such as playing ambient noise and setting timers. Those complaints have only gotten louder as Google shifts its focus from the old Assistant to a new one powered by its Gemini large language model (which itself is worse at some tasks than the AI it’s replacing). Without clear financial upside, there’s little incentive to maintain and improve ambient computing systems.

For an all-knowing AI assistant to work, it needs to interact with a wide range of services, across a wide range of devices, running on a wide range of sometimes-competing platforms. If those interactions don’t directly lead to more revenue, there’s no clear path to profitability for the underlying assistant. Humane may be banking on a subscription model as the answer—the AI Pin requires a $24 per month service fee atop the $699 hardware price—but it also has to keep up with the high cost of generative AI itself.

Ambient computing has been great for little things, like setting kitchen timers, adding items to a grocery list, or looking at family photos, but it’s a far cry from a post-phone computing platform. Amazon and Google have discovered this already, and Humane—and its users—will soon learn that lesson the hard way.