- | 9:00 am

The buildings of the future won’t just be for humans—they’ll be for insects, too

Multispecies architecture increases biodiversity and human knowledge of the insect world.

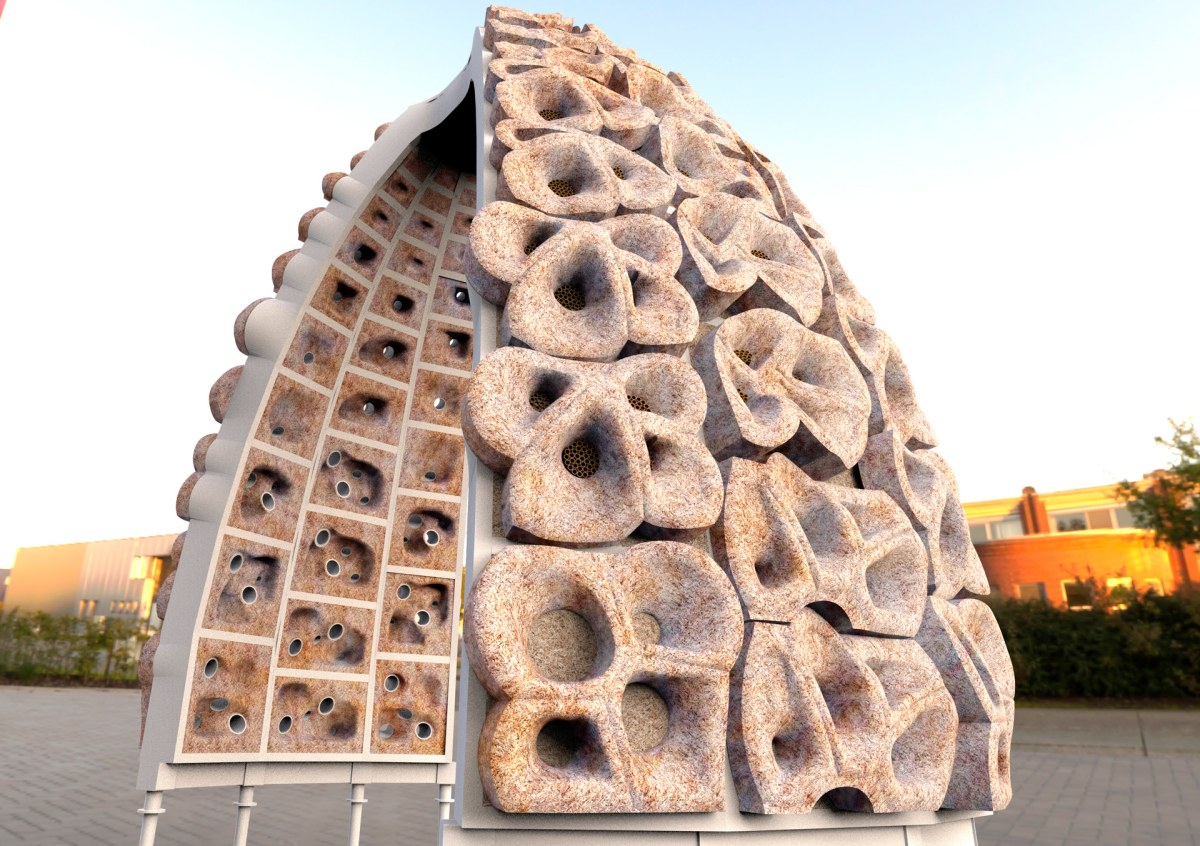

On Governors Island in New York there will soon stand an arching structure that, at first glance, might seem like a sculpture or a work of avant-garde art. It’s about 8 feet high with a globby surface that’s perforated with irregular fist-size cavities. Mounded material around each cavity creates the look of entrances to oversize anthills, or perhaps the suction cups of an octopus. The arch itself is like a slice of an igloo, big enough to walk beneath.

The holes and the undulating surface give the structure a curious, somewhat gastrointestinal look, but they are more than just flourishes of design. Rather, they’re habitat spaces for bees.

The structure is a domed gateway that will be built in April, combining animal habitat and the type of architectural materials that might end up cladding the exterior of a building. It’s a kind of mashup that suggests a radically biodiverse future for architecture in cities—one that erases the line that’s often drawn between human settlements and the natural world.

The arch is the work of Harrison Atelier, led by architect Ariane Harrison, who is also the academic coordinator of the master of science in urban design program at Pratt Institute in New York. Built in partnership with the Bee Conservancy, a nonprofit group focused on countering bee habitat loss, the arch will be installed on Governors Island as a “sanctuary”—a space equally intended for creating bee habitat and engaging people in environmental issues.

It’s an attempt to show that architecture and buildings don’t have to simply erase animal habitat as a result of being built, but that they can create new types of spaces where humans and animals can coexist.

Harrison began thinking about this concept about 10 years ago. She was teaching a seminar at Yale University’s architecture school and decided to center it on the idea of designing for nonhuman species. “I was mocked pretty roundly by some of the faculty at Yale,” she says.

In architecture academia, where the topics of design studios can verge on parody, it could have seemed like just another high-concept, low-practicality idea. But Harrison says the seminar was happening at a time when green roofs were becoming much more mainstream, and there were very real issues with how these high-up garden spaces were failing to attract the pollinators they needed to thrive. Designing around this problem was more than just a theoretical concern.

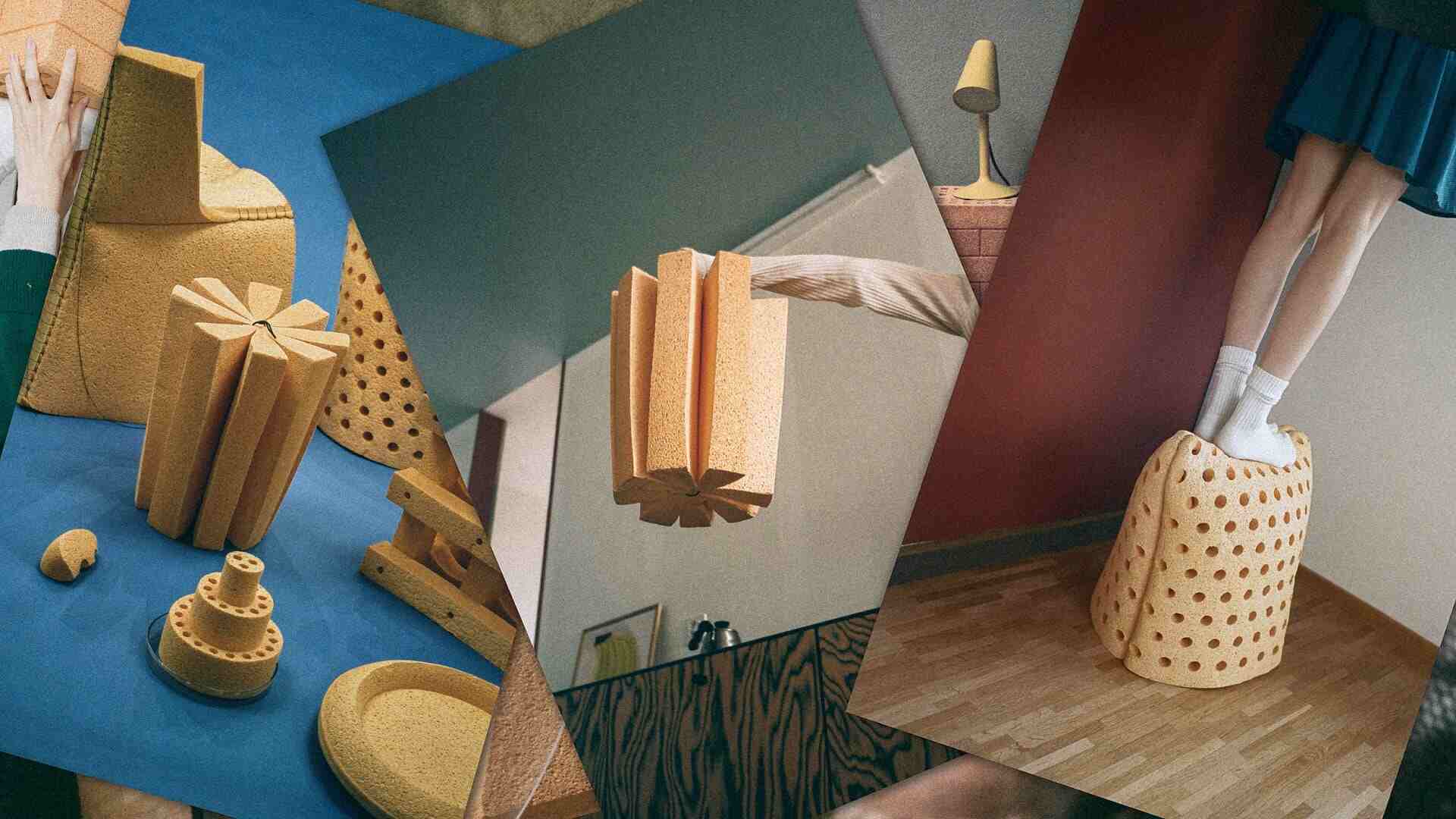

Through her firm, Harrison began designing concepts for structures and the cladding on the exterior of buildings that could provide habitat for animal species without compromising the demands of a human-occupied building. The idea also made sense at the neighborhood scale, carving out spaces in the asphalt and concrete of the city to restore habitats that had long been paved over. It’s work she calls “biodiverse urban design” or “multispecies urbanism.”

Harrison is not the only designer exploring this multispecies concept. A burgeoning movement of “animal-aided design” is using local ecosystems as the framework for determining the design of buildings and landscapes. Bricks are being designed to do double duty as building block and bird habitat. And new, experimental designs are turning animal habitats into the physical armature of tree-based architecture.

Harrison has focused most of her multispecies design on bees. Prototypical pollinators, bees are essential to the livelihood of countless ecosystems around the world. More than 20,000 species have been documented. In the U.S. alone, there are more than 4,000 native bee species, and many are struggling to survive; viable habitat is part of the reason.

“Probably 70% of them live in the ground. All they need is a bare patch of ground, which is surprisingly difficult to locate if you’re a bee,” Harrison says. “Because if you’re in agricultural territory, you are being smothered by pesticides, and if you’re in the city, forget about it.”

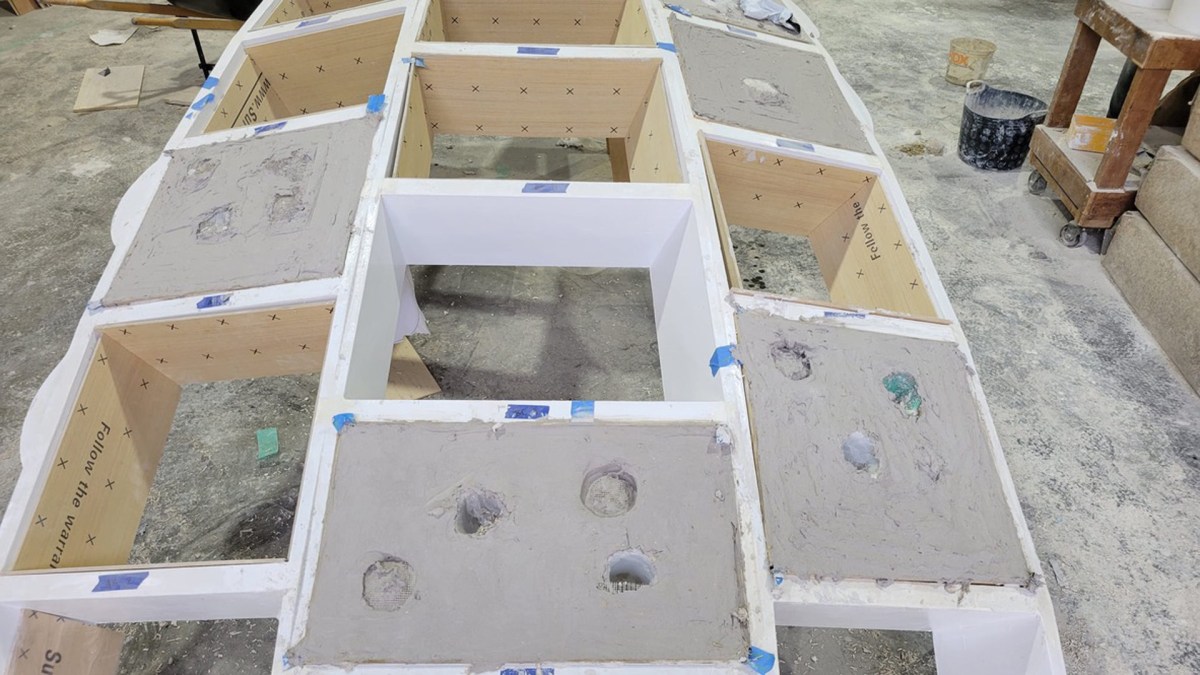

Her firm developed a dome-like pavilion in Hudson, New York, built from punctuated concrete panels with built-in nooks modeled on the habitats used by cavity-dwelling bee species. Constructed on the edge of a field at an organic farm, the pavilion looks like an inflated pufferfish, with spiky protrusions on each of its panels that provide shade for the tube-like cavities the bees inhabit. Concrete worked well for the project, but its high carbon footprint was a downside. Eager to find a more sustainable material, Harrison landed on hempcrete, or a concrete-like material made out of hemp. It’s become the basis of the Governors Island arch.

The structure that will soon be built there has a more organic look on its exterior, and a human-accessible underside. It’s designed to be easily cleaned by humans once a bee’s nesting is complete.

“The maintenance part is actually really important when you’re thinking about viable habitats for other species,” Harrison says. “For some species, a remote, left-alone site is great, but for a lot of the pollinators that my firm is focused on, there needs to be maintenance and cleaning and caretaking.”

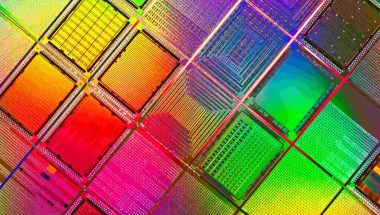

Deep inside these cavities there is also, curiously, a significant amount of technology. Wires, microprocessors, cameras, and power from solar panels are part of an elaborate monitoring system that Harrison sees as critical for this type of multispecies design to not only create habitat but also expand knowledge about the species that use the habitat.

For bees and insects, this is much-needed work. “We have kept track somewhat of birds and certainly charismatic mammals, but only 1% of all insects are assessed, and there’s a massive amount of insects on the planet,” Harrison says. “I was fascinated by this gap and thought any habitat we do has to be cognizant of it.”

Monitoring and gathering usable scientific data from such small spaces is far from straightforward. “We went down into 10 rabbit holes,” Harrison says. Her team looked into using photography, motion sensors, even audio sensors that could measure the sound of a buzzing bee’s wings. “At the same time as we were exploring this, AI became a little more accessible as a tool,” she says, which opened up new options.

In partnership with a team of technologists from Georgia Tech and with funding from Microsoft’s AI for Earth grant program, Harrison’s team developed algorithms that can automatically identify insects in these habitats using images captured by embedded cameras. Training the algorithm on images of insect specimens held in collections at the American Museum of Natural History and Penn State’s Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Harrison’s team refined their identification system to use images from the niches within these architectural structures to automatically name the family in which the insect belongs. “So it’s a fuzzy portrait, but it’s a portrait nonetheless,” Harrison says.

The data collected in this type of system is intended to improve ecological literacy, and Harrison says the structure is a way to bring humans into a closer relationship with species they might otherwise overlook. “When you put this together as a monitored habitat, the habitat needs to be cared for by the human. So does the machine. And the data that emerges from this hopefully helps the human better care for the planet,” Harrison says.

It’s much more active participation in urban biodiversity than just putting up a birdhouse and hoping nature somehow emerges. Harrison says the active engagement required by her pollinator structures is part of reframing the natural world as something that humans don’t just displace but are a part of. “Architecture is not the solution. It’s just a part of it,” she says. “The bigger issue is coexistence.”