- | 9:00 am

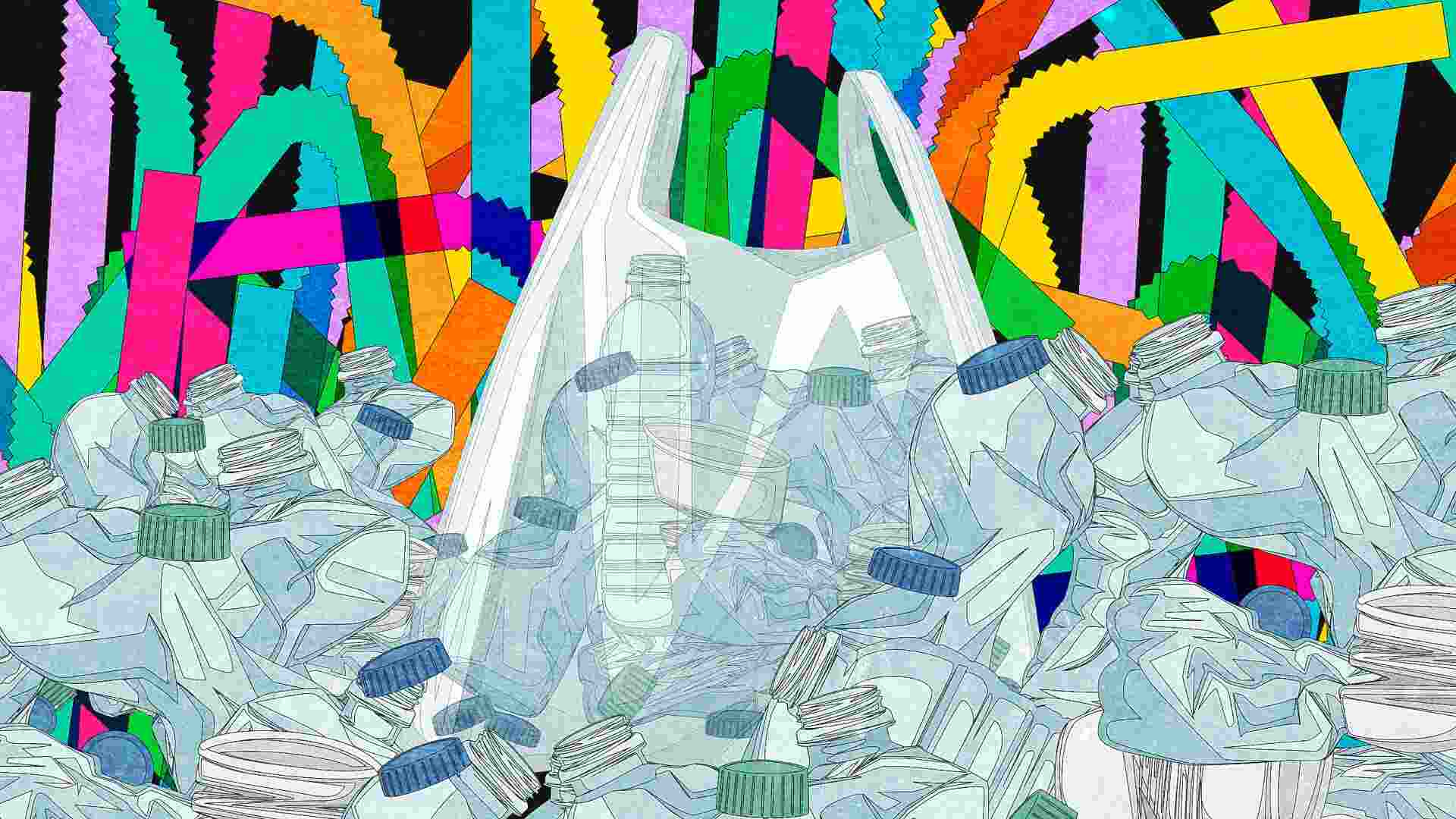

What would it take to ditch single-use plastic?

As global leaders negotiate the world’s first plastic pollution treaty, here are some real-world ways to start phasing out single-use plastic.

Of the 400-million-plus tons of plastic that the world produces each year, more than a third is only used once before it’s thrown out. Each minute, by some estimates, the equivalent of a garbage truck full of plastic waste ends up in the ocean. Most single-use plastic ends up in landfills after a few minutes of use by consumers, wasting the money and CO2 emissions that went into making it.

But some single-use plastic can easily be eliminated, and other plastic packaging can be replaced by reuse systems or other materials. This week, as leaders meet to take the next steps to negotiate the world’s first global plastic pollution treaty, we took a look at some of the ways to begin phasing out single-use plastic.

SCALING UP REUSE

Over the last few years, big brands and retailers have experimented with reusable packaging. Some tested new packaging, including stainless steel packaging for Haagen-Dasz ice cream and Pantene shampoo, as well as systems designed to collect, sanitize, and reuse the containers. Starbucks is testing takeout cups that can be dropped in a bin and reused. Smaller zero-waste stores, focused on selling package-free products, keep growing. Startups have pioneered new products like cleaning tablets that can be added to reusable glass bottles, eliminating the need to ship plastic bottles that are filled mainly with water.

Right now, all of this is still happening at a small scale. Some pilots with large brands at retail stores ran for a short time but never became permanent. For reuse to succeed, companies need to collaborate to build much larger systems. “We need scaled infrastructure and shared infrastructure,” says Marta Longhurst from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, an organization that helps companies shift to the circular economy. “Not every business creating their own reuse models and their own collection facilities and washing facilities, but businesses collaborating and sharing that.”

For reuse to work at scale, she says, it also makes sense to have standardized packages for different product types. (To differentiate brands, companies would have to rely more on labels.) Having one large system would also make it easier for consumers to return packaging, another crucial part of making reuse work.

The organization is pushing for the global treaty to include guidelines and targets for reuse. “That would really send a clear signal to the stakeholders and to the market about the future of reuse, and enable channeling of investment,” Longhurst says.

ELIMINATE UNNECESSARY PLASTIC

Some plastic packaging doesn’t need to exist—for example, individually-wrapped bananas. Clothes shipped in a box arguably don’t need to also be in plastic wrap. It’s possible to sell multipacks of products without wrapping the whole thing in plastic. Tesco, a large U.K. supermarket chain, eliminated 45 million pieces of plastic just by ditching multipack versions of some of its drinks. (Customers still get a discount when buying the drinks in quantity.)

When the nonprofit Ocean Conservancy studied the types of plastic that it found most often in decades of beach cleanups, it highlighted a handful of products that could be eliminated. Plastic shopping bags can easily be replaced; one recent report found that bag bans in five states and cities in the U.S. eliminated around 6 billion bags per year. Ocean Conservancy’s list of products also includes plastic utensils and straws and expanded polystyrene, better known as Styrofoam. “A lot of these items are just so pervasive and pernicious that there’s not a good solution other than to get rid of them,” says Anja Brandon, associate director of U.S. plastics policy at Ocean Conservancy.

The nonprofit, which pushed for a bill in California that requires companies to make a 25% cut in single-use plastic packaging, is advocating for the treaty to include a goal to cut single-use plastic by 50% by 2050. “I have no doubt that businesses are smart and creative and clever and will still figure out how to sell their products under new global rules,” she says.

WWF and other groups want the treaty to include criteria for which plastic should be phased out. “We don’t have replacements for all single-use plastic today, so the way we start phasing down is by looking at a set of risk criteria,” says Erin Simon, the lead on plastic and business at WWF. The list could include how likely a product or type of plastic is to end up in the environment, how hard it is to recycle, and how dangerous it is for nature or human health based on its chemistry.

DESIGN NEW PACKAGING

Companies are starting to find better alternatives to single-use plastic—sometimes in surprising ways. The plastic industry likes to tout the fact that plastic can help keep food fresh longer and prevent food waste. But a startup called Apeel, and others in the space, have designed edible coatings that can protect produce without the need for an extra layer of plastic. A single produce supplier can eliminate tens of thousands of pounds of plastic a year by using the product.

Brands like Heinz and Estée Lauder are testing paper bottles that can eliminate plastic packaging (without getting soggy). Mars, the candy giant, started testing paper wrappers for candy bars last year. Other companies are redesigning products so they don’t need plastic bottles—like shampoo bars instead of liquid shampoo, or toothpaste tablets instead of regular toothpaste. Amazon redesigned some mailers to eliminate plastic Bubble Wrap.

While it’s arguably possible to find creative ways to replace almost all single-use plastic in packaging, other forms of single-use plastic—like the gloves and masks that became ubiquitous during the pandemic—need to be designed for recycling or composting. “Plastics right now are not designed to be recycled,” says Brandon. “So it’s no wonder our recycling system is so broken.” The treaty should also include design guidance for manufacturers, she says.

Though some people argue that recycling can never work, Brandon says it needs to be one part of the solution. “This is not an either or question,” she says. “This is a ‘yes, and . . . ‘ We need to be doing all of it to really move the needle on this issue. Quite frankly, we are running out of time. So yes, we need to start with reduction. And yes, we need to improve our recycling system at the same time to make sure that we can decrease our dependency on the fossil fuels that plastics are actually made out of.”

THE NEXT STEPS AT THE TREATY NEGOTIATIONS

Two years ago, UN delegates agreed to create a legally binding treaty to tackle plastic pollution. This week’s meeting is the fourth so far; in the previous three meetings, negotiators didn’t make progress on substantive issues. Now, they hope to finally negotiate about the text. The treaty is supposed to be finalized this year.

“Our hope is that this week we will take that last chance to really prevent the irreversible economic, health, and environmental damage that plastic pollution is having today, and not kick it down the road,” says Simon. Globally, she says, there’s widespread support for action. In a survey of 24,000 people in 32 countries, the organization found that 85% of people support a ban on unnecessary single-use plastic.

“This whole treaty process has been happening at breakneck pace, from the original resolution a few years ago to now, trying to wrap this treaty up by the end of this year,” says Brandon. “It’s really great to see countries and policymakers from around the world recognize the urgency at this moment and say so in their statements. You hear words like crisis and urgency. And that gives me a lot of hope.”