- | 8:00 am

The stunt factory behind ‘The Fall Guy’ is proving you don’t need AI to create a spectacle

‘The Fall Guy’ director David Leitch and his 87North cofounder Kelly McCormick respond to AI’s rise with a major flex—and an assist from Ryan Gosling.

That poor henchman over there has a hammer stuck in his forehead.

The hammer is made of foam, wrapped in duct tape, and technically it’s stuck to his head with clear tape, not in his head, but still. Tough break. His masked killer, dressed head to toe in black, ninja-style, yanks the hammer out of (off of) his skull, and he tumbles backward onto the mat. One henchman down, four to go.

Afternoon sunlight streams in through a stained-glass window high above the dojo floor of a converted cathedral on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, filling the space with the warm glow of fight-choreography heaven. Off to the side, observing and taking mental notes, are veteran stunt performer turned director David Leitch and his producer wife, Kelly McCormick. Two years ago, they converted this building—the headquarters of their production company, 87North—into an incubator for the kind of car-rolling, helicopter-dangling action movies that studios usually make on a computer nowadays. They train actors here, block out fights, and shoot and edit rough versions of complete sequences. It’s a full-service action factory, all under one vaulted roof.

“It’s probably the coolest production office I’ve ever been to,” says Ryan Gosling, who spent an entire Christmas season here in 2022 training for 87North’s latest movie, The Fall Guy, based extremely loosely on the ’80s television series, with Gosling taking over for Lee Majors as a breezy blue-collar stuntman named Colt Seavers. Another actor who worships at the church of 87North is Bob Odenkirk, star of Better Call Saul, who spent two years training with Leitch, McCormick, and their team to transform his sketch-comic body into a hit man’s for the company’s revenge thriller Nobody, which became a surprise hit in 2021. “In fact,” Odenkirk says, “I’m going to 87North twice this week to train, even though there’s no movie in close proximity”— Nobody 2 is still being written—“because I’ve grown to love the vibe. It reminds me of a comedy writers room.”

He might run into Ke Huy Quan, the Oscar winner for Everything Everywhere All at Once, who’ll be visiting the cathedral soon to learn the fight choreography for 87North’s next project, With Love, due out in 2025, about a hit man turned real estate agent whose brutal past catches up with him. (The guy on the tatami mat wielding the foam hammer, it turns out, is Quan’s stunt double.) Wander into this place on any given day and there’s a good chance some famous actor will be here learning how to murder people.

“We call it ‘the Church of Pain,’ ” McCormick says with pride.

In the half-dozen years since she and Leitch launched the company, 87North has made three stunt-saturated hits in swift succession: Deadpool 2, with Ryan Reynolds; Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, with Dwayne Johnson and Jason Statham; and Bullet Train, with Brad Pitt. The films, all directed by Leitch, grossed nearly $2 billion combined. The Fall Guy, part of 87North’s ongoing first-look deal with Universal, is stuffed with the kinds of stunts Leitch never imagined any studio would be lavish enough to let him shoot, including a “cannon roll”—a flipping car with a stuntman inside—that set a Guinness World Record. In the film, the car flips an unprecedented eight and a half times. Eat it, Casino Royale. (The stuntman on that film, Adam Kirley, only made it to seven.)

“I would’ve been happy to say I did not do any of my own stunts in this movie,” Gosling says, but he plays a literal stuntman, “so it was important for me to do some of them. And they happened to just fall in line with some fears I have that needed to be faced.” His fear of heights, for instance. “My body turns to stone after a certain amount of stairs,” he says, and The Fall Guy opens with Colt performing a 200-foot plummet. “It was the right way to start the film, and I’m happy that it’s over.”

Much of Gosling’s character in The Fall Guy, which hits theaters May 3, is drawn from Leitch’s 20 years of experience doing stunt work himself, so it’s no stretch to say that Leitch’s whole career has been building up to this film. “It’s about the wish fulfillment of being a stuntman,” he says, versus “the reality of being a stuntman.” It’s also a $125 million mission statement for 87North and a rallying cry for an entire field of Hollywood performers whose defining characteristic has traditionally been their invisibility, and who always seem to be threatened with extinction by some new and mind-blowing technology, whether it was computer-generated imagery 25 years ago or artificial intelligence now.

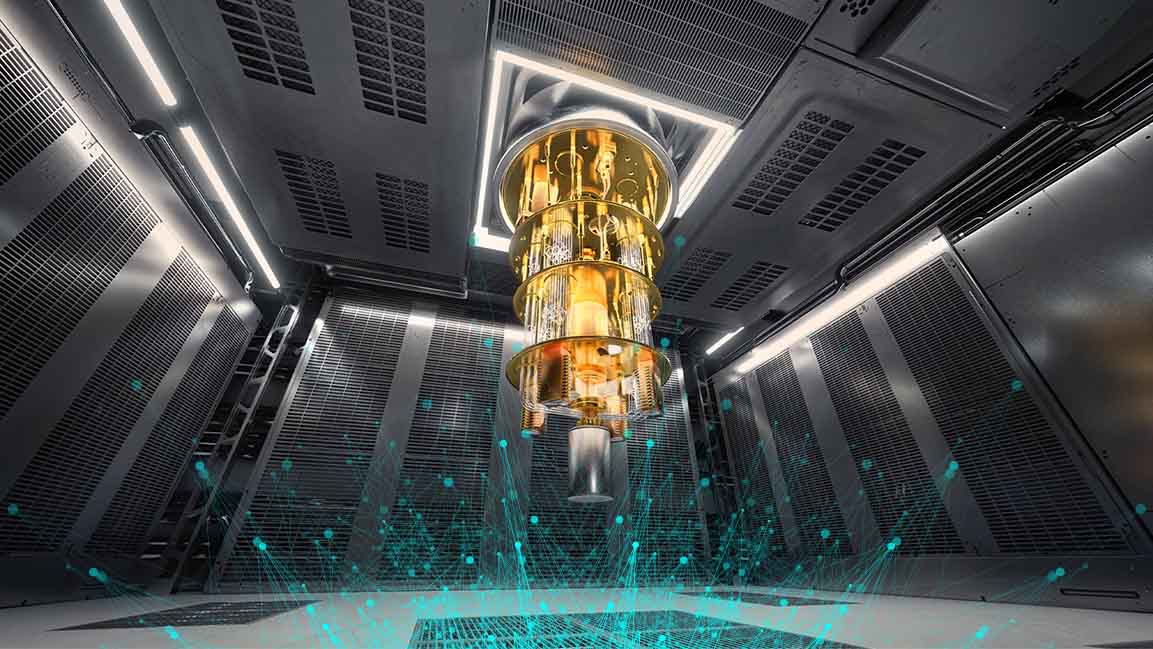

It turns out, though, that stunt artists are hard to kill. AI could wreck the stunt industry as we know it, or it could be rocket fuel, the same way that CGI turned out to be after everyone finished panicking about it. “Sometimes technology feels scary, and then artists figure out how to use it in this really compelling way,” Leitch says. “I hope that’s the future of AI.”

Practical stunts, though, have always held one critical advantage over CGI: They’re cheaper. Even now, CGI requires actors and a factory full of graphic artists who spend months producing digital humans who nonetheless look like they were born and raised in Uncanny Valley. AI, which is generated entirely on a computer, erases that advantage. Which begs the question: How much longer will studios finance the wildest fantasies of stunt connoisseurs like Leitch? Why not just leave it to the computers? Tools like Sora—OpenAI’s text-to-video engine, which generates photorealistic short videos with just a few basic prompts—promise to empower amateurs to do the work of entire visual-effects studios right from their laptops, so who knows what Sora9 or Sora10 will be capable of? Perhaps AI will be like the bigger, badder villain who shows up in a franchise sequel: the stunt profession has never faced an adversary quite like this.

Once upon a time, when he was the anonymous stunt performer taking a hammer shot to the head, Leitch earned himself the nickname “Rubber Guy” because he always bounced back up. He began his stunt career at age 23 with a role in a Batman theme-park show at Magic Mountain, then worked as a double for Jean-Claude Van Damme, who Leitch says got very jealous when he moved on to doubling for Brad Pitt in Fight Club and The Mexican and Hugo Weaving (aka Agent Smith) in the Matrix sequels. By the time Leitch doubled for Matt Damon in The Bourne Ultimatum, he was coordinating entire stunt sequences himself, and soon he became a second-unit director—the one who orchestrates all the action sequences that the director gets credit for.

“Most directors don’t have an expertise in action—you hire someone to do that. And nine times out of 10, it’s the stunt coordinator,” Leitch says, sitting beside McCormick in their second-floor office at the cathedral. They have the easy amiability of native Midwesterners: McCormick grew up outside East Lansing, Michigan, and Leitch in Kohler, Wisconsin, where they make the faucets. As they talk, grunts and pops and oofs and arghs from the stunt team downstairs float up through the open door.

Leveling up to the top job from second-unit director is typically among the toughest feats in Hollywood. But in 2012, McCormick, who was Leitch’s manager at the time, came across a script for a revenge thriller called John Wick. Keanu Reeves, who was attached to star, vouched for Leitch and his action-design partner, Chad Stahelski, and the $20 million budget was modest enough for Lionsgate, the film’s backer, to roll the dice. (Leitch and Stahelski codirected, but Leitch went uncredited due to a technicality with the Directors Guild.) Plus, Lionsgate was able to proceed with confidence thanks to a preproduction technique Leitch and Stahelski had devised called “stunt-viz,” in which they shoot and edit test versions of entire action sequences before the actors even show up to train for them. Stunt-viz saves time and money, reduces uncertainty, and has become a staple not just in 87North’s process but across the stunt industry.

John Wick wound up making $86 million worldwide, leading to more directing opportunities for both Leitch and Stahelski. Stahelski stuck with the John Wick universe, directing three sequels and counting. Leitch and McCormick, meanwhile, got married in 2014 and formed their own production company in order to focus on making the kind of action movies they prefer—funnier, more mainstream, and crowd-pleasing. Movies like The Fall Guy.

The Fall Guy is an action movie within an action movie, in which Colt gets called to set when the movie’s star, Tom Ryder, played by Bullet Train’s Aaron Taylor-Johnson, goes AWOL. Colt’s task is to keep the production on track, locate Tom, and along the way try to rekindle his love affair with the movie’s rookie director, played by Emily Blunt. Like real stunt artists, Colt expects no credit for his unique skills and gets none. “It is such a collision of personality types,” McCormick says. “You have to be a ham, you have to want to perform, and then you have to never want to be seen. You have to want to perform dangerous things, but you have to be safe about it.” (For more about 87North’s push to get stunt work recognized at the Oscars, click here.)

The Fall Guy is filled with eyewinks to the indignities endured by stunt performers, including a moment when Colt gets steered into a 3D body scanner the moment he arrives on set. Before he can even get a cup of coffee, the studio has already made a digital replacement for him. The scene was written to be a joke about stunt life in the CGI era. But last summer, while the film was shooting in Sydney, “AI was becoming a hot topic,” Leitch says, both in Hollywood, where it became a central issue in the industry’s strike negotiations, and in the wider world. Now their little in-joke plays more like gallows humor.

“It’s becoming scary,” Leitch says, “because now it’s like, well, when are they going to figure out real motion? When are you going to not be able to tell a digital double from a human double?” The technology isn’t quite there yet, but like everything else with AI, it’ll be here sooner than we expect.

Ed Ulbrich, chief content officer and EVP of production at generative AI visual-effects company Metaphysic, believes these are the wrong questions to ask. He likens this moment to the advent of CGI, which he witnessed firsthand as an early executive at Digital Domain, the visual- effects company cofounded by James Cameron that created the liquid-metal T-1000 in Terminator 2. “Everyone leaps to, Oh my God, we’re going to eliminate filmmaking,” Ulbrich says. “Well, I have a different view on that.”

The future of filmmaking with AI, he argues, “is about empowerment versus replacement,” and it’ll imbue artists with “godlike powers because there’s no more limit to the imagination.” He cites as an example the film his company is working on now, with director Robert Zemeckis, called Here. With the help of AI, Tom Hanks and Robin Wright perform every scene as their characters mature from young adulthood to old age. It’s a drama set in a single room, adapted from a graphic novel, and in the CGI era it never would’ve been green-lighted, because it’s an indie-scale story that would’ve required a Marvel-size budget. “Stories that previously couldn’t have been told now can be,” Ulbrich says. “I know. I’m seeing it. It’s happening already.”

Leitch ultimately believes that stunt work will endure because, on a subconscious level, “humans like watching humans.” The more ubiquitous that AI becomes, the more that audiences will thirst for the real thing, the same way that CGI-heavy franchises like the Marvel movies help make The Fall Guy feel like such a tangible breath of fresh air.

“We don’t want the industry to be driving toward mediocre content,” says Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, national executive director of SAG-AFTRA, the union that represents actors as well as stunt performers. “I’ve made this point to the studios: It’s important they realize what it is they have that’s special, and that’s human creative talent. That’s what distinguishes these companies from OpenAI or Google or whomever.”

Emma Tammi, the director of last fall’s hit thriller Five Nights at Freddy’s, made the movie’s killer mascots using traditional animatronics built by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop because they matched the pizzeria’s ’80s vibe and would offer a degree of authenticity that she knew audiences would appreciate. “If those animatronics had been flying in the sky and doing constant somersaults” using CGI or generative AI or anything other than the real thing, Tammi says, “I just can’t imagine that those scenes would feel the same.”

Universal has franchise ambitions for The Fall Guy, and indeed, according to Gosling, a second movie is already in motion. “The sequel sort of wrote itself,” Gosling says. “We already know [the plot] intimately.” For the time being, though, Leitch’s next project is up in the air. For five days in early February, Leitch had been unofficially attached to direct the next Jurassic Park movie, produced by Steven Spielberg. The Fall Guy includes an homage to a classic stunt from Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark in which Indiana Jones gets dragged on a rope behind a Nazi military truck; in Leitch’s version, it’s Gosling getting dragged on the lid of a dumpster chained to the back of a truck. When Leitch and McCormick screened The Fall Guy for Spielberg, he was so charmed by their affection for old-school stunts that he asked if Leitch would like to try creating some with dinosaurs.

The project needed to start shooting by July, though—not enough time to put their 87North stamp on the script and also manage the May rollout of The Fall Guy. As Leitch explains it: “Everyone had to look each other in the eye and go, ‘Can we do this version the way we would want to do it in the amount of time we have?’” The answer was no. They’ve already got their hands full trying to save their art form from future annihilation. So they turned down Spielberg and, like the meme of the cool guy walking away from an explosion, they didn’t even look back.

THE BOLD AND THE FIRE-RETARDANT: 87North’s The Fall Guy responds to the rise of CGI and AI with force, breaking stunt records and keeping costs death-defyingly low. Here, the company breaks down three key stunts.

BY KELLY CLOONAN