- | 9:00 am

It’s way too late to stop TikTok

TikTok’s FYP recommendation algorithm is being replicated across the internet—putting us all in individual universes, built by unseen hands.

A woman in leggings and Ugg boots poses for a selfie. A blond millennial strides along a porch in a leopard-print blouse. A leather recliner stretches across a snug living room. The images scroll by under one’s thumb, a blur of shoppable scenes.

I’m getting an early look at the new Inspire section on Amazon’s smartphone app. Set to launch this year, it’s the company’s response to TikTok: a personalized, machine-curated feed of user videos, all with “buy” links. Despite having little interest in the actual products on each page, I find myself lured in. “It’s one of those things,” confesses the Amazon spokesperson who arranged the demo, “that can [take you] down a happy rabbit hole.”

These days, everyone’s rabbit hole is a little different. Whereas in the earliest years of the internet, when each web page, icon, or piece of content was meticulously designed and more or less static, what we see online today is increasingly created in real time and tailored to individual users. The product listings on your Amazon homepage change according to your shopping habits. The songs queued up by your Spotify Discover Weekly playlists are tuned to your latest listens and likes. Your Google search results account for your late-night web surfing.

TikTok has taken that idea even further with its For You Page (FYP) feed. The eccentric, confusing, and captivating mix of rapid-fire scenes on your FYP have been optimized in response to your every tap, pause, and glance online. The result is a sort of customized cable TV channel, reflecting your (supposed) tastes.

The major tech platforms are now racing to keep up. Services including Instagram, YouTube, and even Amazon have cloned TikTok’s design and integrated similar flickable video streams into their platforms. (The last time we saw such shameless UX theft was circa 2016 when companies from Facebook to LinkedIn started copying the Snapchat Stories format.) More profoundly, the FYP represents a shifting internet, one that’s increasingly served up by automation—and different for each person.

It’s a phenomenon that Mark Rolston and Jared Ficklin, founder and partner, respectively, of the tech-focused design firm Argodesign, have dubbed the “quantum internet.” The name comes from research in quantum physics, which shows that atoms don’t behave as particles or waves until they’re observed. In this case, the internet is now powered by autonomous computer code that generates many of the things we see on demand. The content, in other words, exists only for the individual trying to observe it. “When we look at this [quantum] process,” says Rolston, “[software] becomes very different . . . you’re never sure what may come out.”

We are, quite literally, no longer on the same page.

The FYP-ification of the internet actually began well before TikTok invaded our consciousness in 2018. Facebook famously shifted, in 2007, from a chronological feed of your friends’ posts to one that prioritized them based on algorithmic choices. A decade later, Netflix’s Recommendation Engine sorted movies and shows by users’ “tastes,” even customizing poster art to entice viewers. By 2018, more than 70% of the content watched on YouTube was recommended by an algorithm.

Today, hundreds of millions of people use the same platforms, but no two of us see these sites, apps, and feeds in the same way. What we see is shaped by our habits—aka our data, filtered through the corporate goals of the platform makers. Our actual preferences and aspirations have much less to do with it.

Over the past decade, these platforms have craftily rebranded their user surveillance as computer intelligence focused on making our lives easier. “The internet enabled firms to start hoovering up personal data, combining them into streams, and [making] inferences about us,” says Sarah Myers West, managing director of New York University’s AI Now Institute, which studies the social consequences of AI. Juiced by rapidly accumulating data, the growing computational power of the cloud, and constantly improving computer science, these platforms have grown supremely powerful at curating products, updates from friends, and multimedia into hypnotic feeds.

There’s a price, of course. “These firms are optimizing for things that allow them to make money,” says West, “which is attention, your willingness to click on an advertisement, and your willingness to make a purchase.”

We’ve seen the consequences of this: Information bubbles that can be—at their most anodyne—amusing time sucks. At their worst, they can lead to self-destructive thoughts and behaviors, radicalism, even genocide. We’re just beginning to grapple with their effects. Social media companies are under scrutiny by lawmakers for their potential to unleash misinformation and manipulative content. In January, Seattle’s public school district filed a groundbreaking lawsuit against TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and Snapchat, accusing the companies of targeting children with addictive content that drives depression, anxiety, and cyberbullying.

One hurdle to any regulation is the ephemeral nature of these individualized feeds. Then there’s the opacity of the algorithms that power them, which makes their full impact almost impossible to measure. Algorithmically curated content rolled in as a fog. It’s now so omnipresent that we’ve forgotten what it’s like to see the world clearly. And this is when humans are still generating the content.

We got a taste last year of what comes next. Generative AI platforms, including Dall-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, opened to the public and revealed just how skilled they are at producing detailed, fantastical, and convincing images, summoned from just a few typed words. In late 2022, when OpenAI unveiled ChatGPT, which can capably research and write articles, poems, screenplays, and jokes, it became clear that within a few years, algorithms could well be both the curators and creators of the posts in our FYP feeds. (Case in point: Facebook and Snap have both announced generative AI features in the past few months.)

This winter, New York’s Museum of Modern Art unveiled Unsupervised, an installation by data artist Refik Anadol, which includes a giant digital canvas that dreams up a new piece of art 30 times per second. The system learned to make art by examining images of the museum’s 100,000-piece collection. What it didn’t incorporate into its “thinking”: any human descriptions, or labels, of the art. “It’s what happens when you don’t have human-made bias,” Anadol says. The effect is an awe-inspiring, ever-changing animation of computer thought, a painting that might morph from a sketched floor plan to an abstract expressionist splatter to a melting wallpaper in mere moments. Before you can process what you’re seeing, the machine has already moved on to the next image in a fervent race with no finish line.

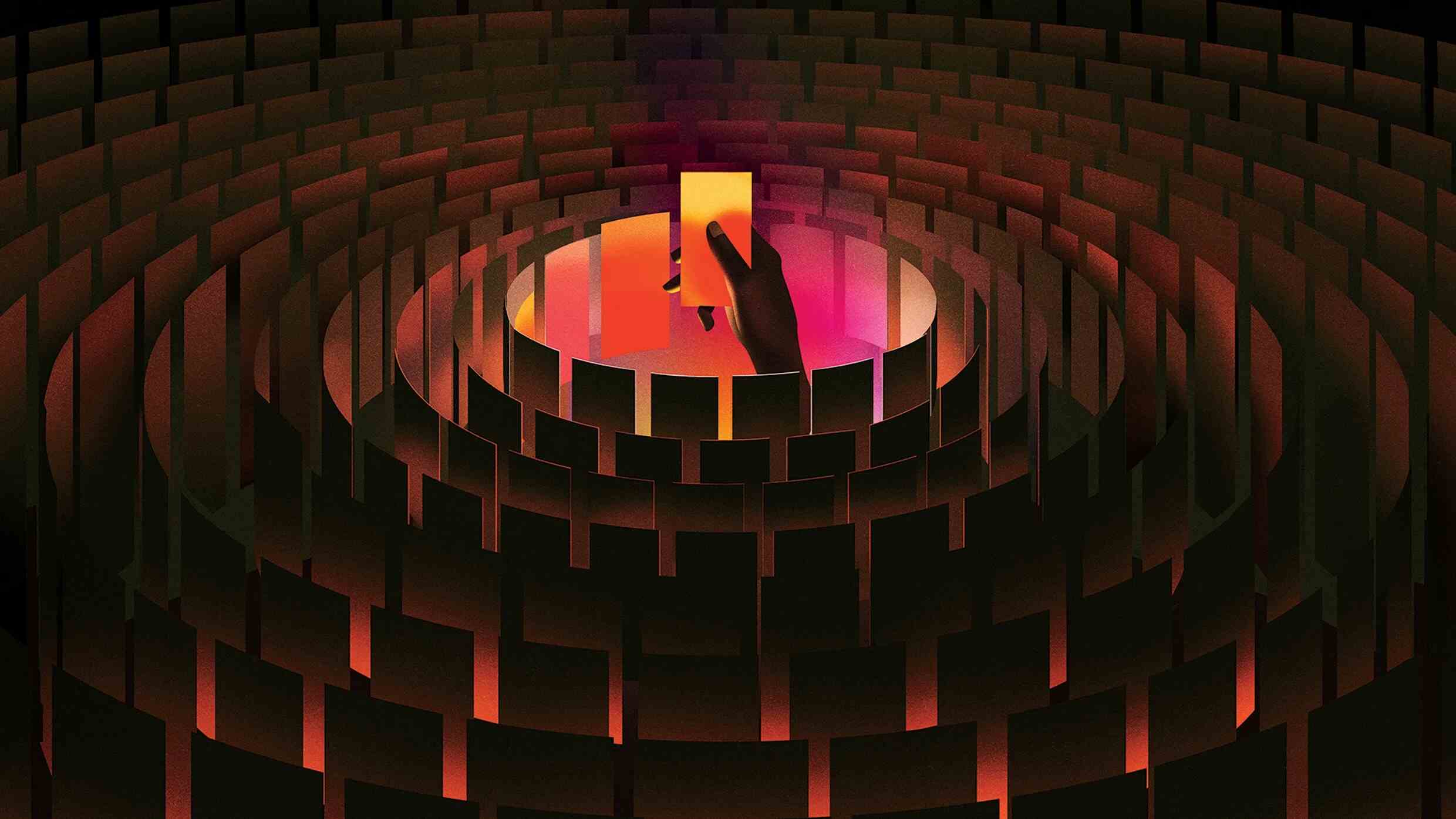

Now imagine an FYP supercharged by generative AI for every one of the 8 billion people on Earth. Pop culture has already been wrestling with this prospect. From the intersecting multiverse of Avengers films and Into the Spider-Verse to the cross-reality body hopping of Everything Everywhere All at Once, we’ve been attempting to grasp the infinite since algorithms started chasing it.

In the real world, this phenomenon will likely beget a multiverse of banalities: Your FYP feed might wind up looking like a bottomless pit of AI-generated episodes of House Hunters or The Office (seasons 10 to 10,000), while mine consists of fantastical alien influencers, producing myriad new dance memes. Generative AI also will build realms that are much more dangerous, as algorithms find evermore innovative ways to circumvent content-moderation efforts. Just as humans have learned to stay within the bounds of YouTube’s nonviolence policy by posting videos that are as violent as possible without crossing the line, AI might automate these efforts. “We’ll have videos where people are punching each other but there’s no blood, or maybe the blood isn’t red, it’s green,” says Jeff Allen, a former data scientist on Facebook’s integrity team who cofounded the Integrity Institute to address the ills of social media. “This [strategy] applies in every space, like misinformation. How much can AI lie before it sets off alarms?”

One prospect is certain: As long as corporations are paying for all that machine learning—and profiting from its user engagement—the future will be channeled toward their aims. And in that multiverse, the endless creativity of these algorithms could well end up serving just another store selling just another thing. Humankind is on the cusp of glimpsing the infinite, but all we might find there is a pair of Ugg boots.