- | 9:30 am

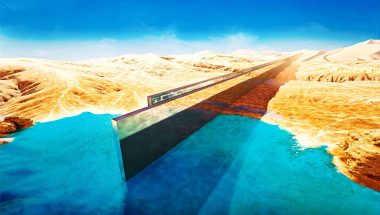

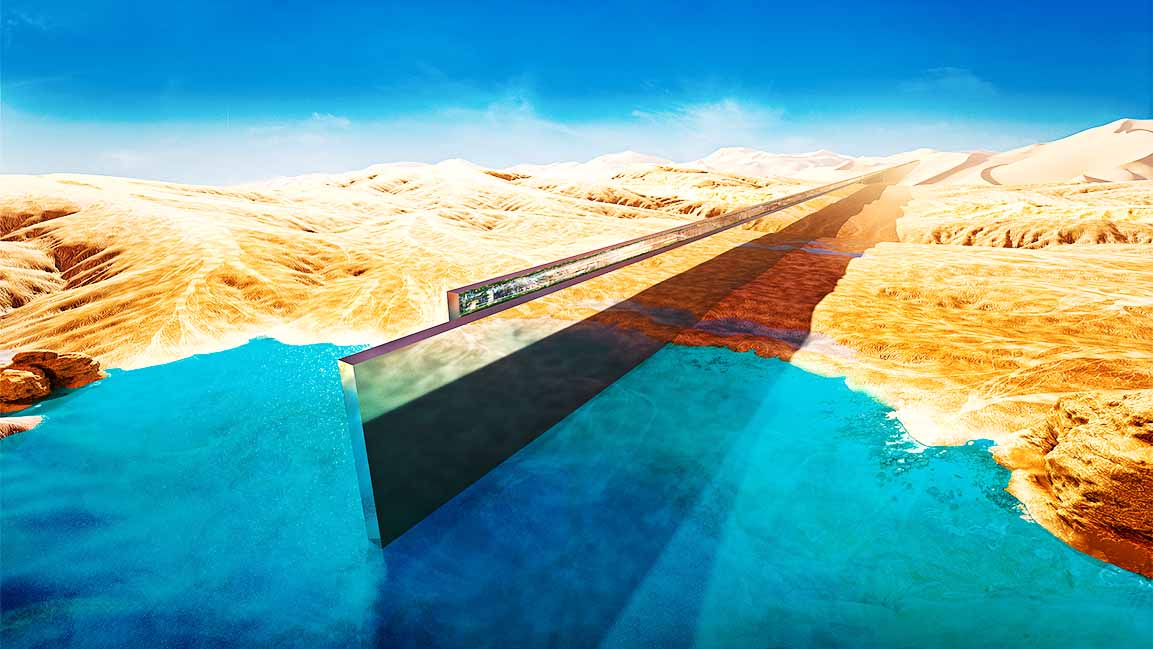

These floating triangle buildings could be the future of coastal cities

With sea levels rising, more cities may need to build on water.

The decorative ponds surrounding the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam have been taken over by a massive floating structure. Looking like an oversized camping tent, the structure is a cavernous wooden A-frame, rising more than 20 feet but floating effortlessly on a grid of plastic pontoons. It’s part installation and part provocation: In a country, and a world, where low-lying cities are facing increasing risk from sea level rise and flooding, the floating structures are a vision of the way buildings may soon have to be built.

The structures are the work of Kunlé Adeyemi’s Amsterdam-based architecture firm NLÉ, which is behind a new exhibition at the museum exploring what he calls Water Cities. A Nigerian architect and designer, Adeyemi gained fame for designing a floating structure for an informal community in Lagos. With coastal communities around the world facing increasing risks from climate change, his design approach has grown into a kind of manifesto for how buildings and cities should be redesigned to accommodate more water underfoot.

This thinking is now on display in and around the Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam’s museum for architecture, design, and digital culture, but the concept dates back to 2011, when Adeyemi and his firm began researching affordable-housing solutions in the African context.

NLÉ found inspiration in the informal fishing community of Makoko in Lagos, which has many homes on stilts directly above the water. Hand-built using basic materials, the dwellings are a low-cost way around the high prices of land and construction, but they lack the structural reliability of formal architecture. Working with the community, the designers adapted this vernacular style to create a robust triangular structure that could float on the water using pontoons as its base. Funding from the United Nations Development Program followed. In 2013, the completed building became known as the Makoko Floating School, with its two upper levels used as teaching spaces for children and the open lower level as a multifunctional community space.

At one point during the project’s design phase, a huge storm rolled through Lagos, flooding many homes, including some in Makoko. Adeyemi says the storm brought home the reality that a floating structure, by its nature, would be resilient as extreme weather becomes more common. “I realized that we’re not only tackling the issues of affordable housing, we’re also dealing with climate change,” he says.

The Makoko Floating School sat in the lagoon for three years, despite being declared an illegal structure by the city’s government and suffering from mismanagement and neglect. A second version was displayed at the prestigious Venice Architecture Biennale in 2016, winning its Silver Lion award. About a week later, torrential rains hit Lagos and the original floating school collapsed.

“The key thing is, it was always a prototype,” Adeyemi says. The experience of the first iteration’s collapse has underscored the need to continue researching the concept, he says.

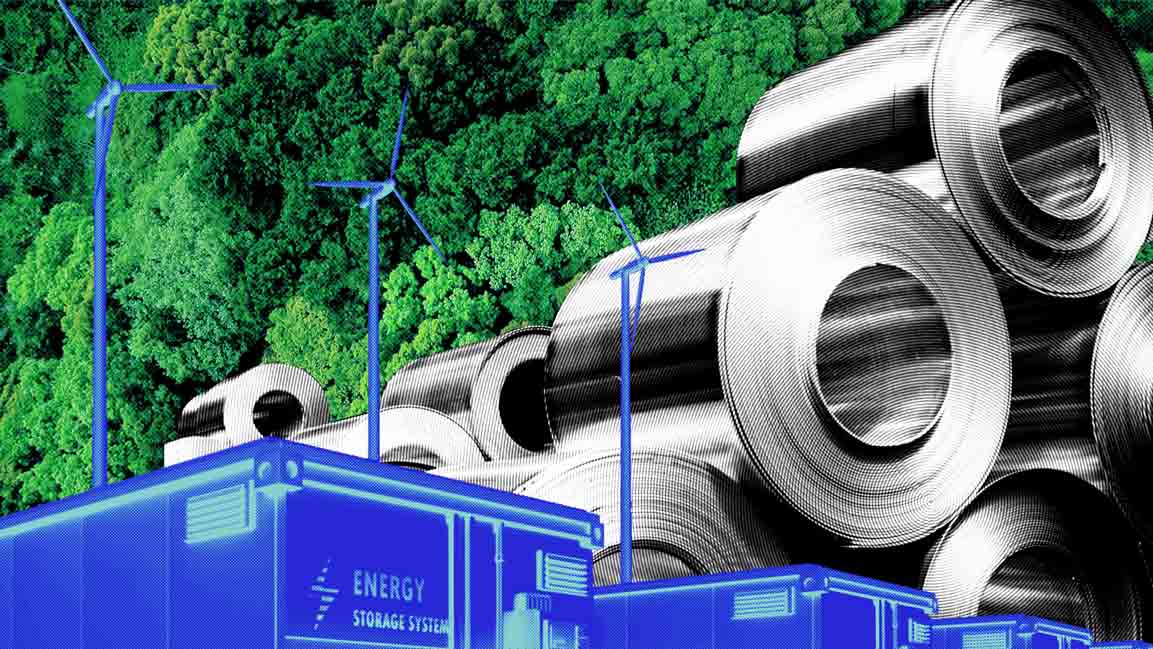

That’s led to more than a decade of work exploring how floating structures can help urban areas adapt to rising sea levels and flooding. The collapsed prototype has become the basis for what Adeyemi calls the Makoko Floating System, an adaptable kit-of-parts design that can create similarly floating buildings for various contexts. Adeyemi calls it “a vision of creating an ecosystem that allows water in the urban fabric. It’s part of a new way of urbanism that doesn’t fight water but learns to live with it and adapts to it.”

The Makoko Floating System has since been installed in a lake in Bruges, Belgium; in another lake in Chengdu, China; and as a permanent three-structure music performance-and-recording studio on a bay in the West African island nation of Cape Verde. “Every time there’s always an improvement. We always learn something or try something different,” he says.

The system has evolved to become a prefabricated timber structure available in three sizes that can be self-built by its users, by hand. It’s also designed for disassembly and reassembly, and Adeyemi expects the structures to be moved as needed.

The installation at the Nieuwe Instituut envisions the floating structures as the basis for a new kind of urban design, with floating buildings and infrastructure providing the essential elements of fast-growing coastal communities in places like Africa and Asia. Adeyemi says water-based communities have existed in these regions for hundreds of years. Formalizing their architecture, he argues, will be one way to adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

Getting there, Adeyemi acknowledges, will require a big shift in the mindset of the people and institutions that plan and build cities. “This is something that will take a long time,” he says. “We hope there will be more pioneering, more forward thinking, more progressive mayors and city leaders, and even developers who are thinking differently about how they build and how we create cities.”