- | 8:00 am

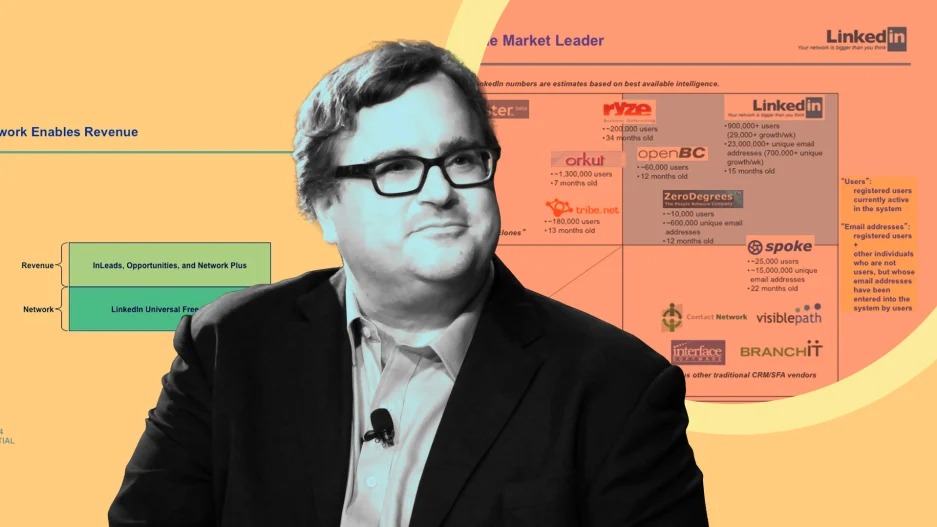

This 2004 LinkedIn pitch deck is an amazing, nostalgic time capsule

Reid Hoffman and his cofounders were seeking funding in an era when eBay was hot and Friendster was better known than ‘TheFacebook.’

For our new oral history of LinkedIn, we talked to dozens of people and pieced together a detailed story of how the business-centric social network rose from a mere idea in 2003 to the indispensible global platform it is today. But even at 6,000-plus words, our account couldn’t cover the whole tale from every angle. A whole chapter could be written about August 2004, for instance, when LinkedIn was a promising but not particularly well-known startup nearing the million-member mark and looking to secure funding. Thankfully, Hoffman captured it himself by writing a blog post about it when the company turned 10 in 2013, including the pitch deck that he had used to seek Series B funding from investors.

Hoffman’s post is a uniquely rewarding look at a key moment in its history. He extensively annotated each slide, offering context, explaining what the company did right, and acknowledging where he’d switch things up if he were making the case all over again after almost another decade of experience.

His 2013 analysis of the pitch deck was aimed at other entrepreneurs who might learn from LinkedIn’s success. (The 2004 presentation made a compelling enough case to help the company raise $10 million in funding, led by VC firm Greylock, where Hoffman is now a partner.) But it‘s worth digging into even if you’re just curious about the gnarly details of persuading venture capitalists to hand over bushels of money when you’ve yet to earn your first dollar of revenue.

Beyond those lessons, the deck is also an evocative snapshot of where the tech industry was in mid-2004, when it was still recovering from the original dot-com crash and didn’t know that another boom was on its way. Among the things I learned, or at least hadn’t thought about in years:

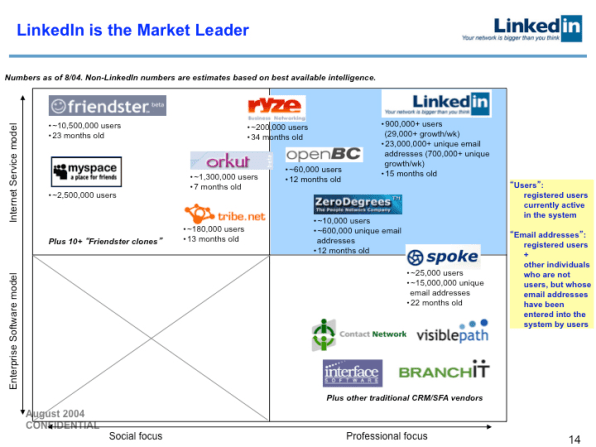

2004’s social networks got washed away—except for LinkedIn. The deck references numerous other recently founded social networks. Some competed directly with LinkedIn by having a business focus; others related more to personal pursuits such as dating. Three of them—Friendster, MySpace, and Google’s Orkut—retain some name recognition today, largely for having been flashes in the pan rather than enduring successes. But the deck lists even more social startups that mattered so briefly that they aren’t even remembered for being obscure: Contact Network, OpenBC, Ryze, Spoke, Tribe, ZeroDegrees, and others. (I’d forgotten about them myself until we talked to some of their founders for our oral history.)

Facebook wasn’t a startup role model yet. Mark Zuckerberg had launched his social network from his Harvard dorm room the previous February; it had quickly hooked his classmates and attracted a little broader attention. In June, Rachel Metz, then of Wired, had even written about the inquiries “Thefacebook” was getting from people who wanted to invest in it or buy it outright. But the venture capital firms on Silicon Valley’s Sand Hill Road who Hoffman was courting weren’t yet obsessed with Facebook, if they’d heard of it at all—so the deck doesn’t mention it.

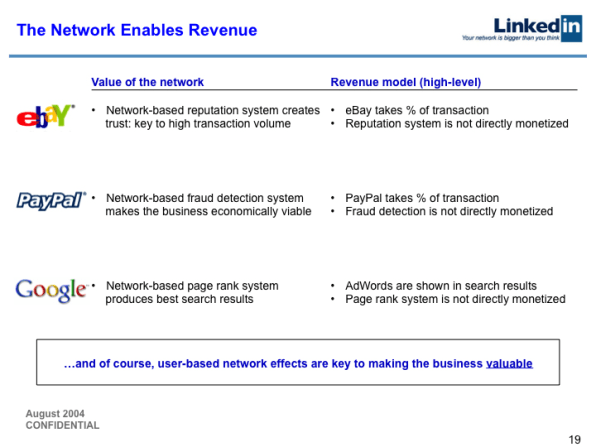

Google was cool—but so were PayPal and eBay. Hoffman’s deck positions LinkedIn as a sort of Google for searching for professional people, which makes perfect sense: He was preparing his pitch the same month that Google went public. However, it also dwells on LinkedIn’s similarities to PayPal and eBay, both of which were still sexy examples of startup success rather than the venerable, largely mundane institutions they later became. (As Hoffman mentions in his annotations, spotlighting PayPal in his presentation helpfully reminded potential investors that he’d been a member of its founding team—his primary claim to fame in 2004.)

Web 2.0 wasn’t called Web 2.0. LinkedIn soon became known as part of a wave of new websites that were more interactive and social than those that preceded them—a trend that was summed up by the catchy term “Web 2.0.” But that phrase didn’t get popularized until O’Reilly Media held its first Web 2.0 Summit conference a couple of months after LinkedIn was making its pitch. The deck uses the now-quaint variant “Internet 2.0” to describe the same concept.

One of the 21st century’s most powerful business models still needed explaining. The notion that online networks get more valuable as they get bigger wasn’t new: Metcalfe’s Law had been around for 20 years. But hot social networks such as Friendster hadn’t begun monetizing their users. Indeed, the venture capital community wasn’t confident that social networking of any sort would turn into a real business. So Hoffman’s deck patiently explains that it is possible to make money from a free social network, and spells out how LinkedIn intends to do it. Though that plan evolved as the company grew, it worked. And last year, as part of Microsoft, LinkedIn made more than $14 billion in revenue.

Successful entrepreneurs rarely discuss their techniques as openly and thoughtfully as Hoffman did when he revisited his 2004 pitch. Again, I encourage you to read his blog post for yourself. And if doing so puts you in a mind to check out other startup-funding presentations, head to PitchDeckHunt. It has hundreds of them, from the historic (Airbnb, Uber, and—in its own way—even Theranos) to the merely hilarious (Fyre Festival).