- | 8:00 am

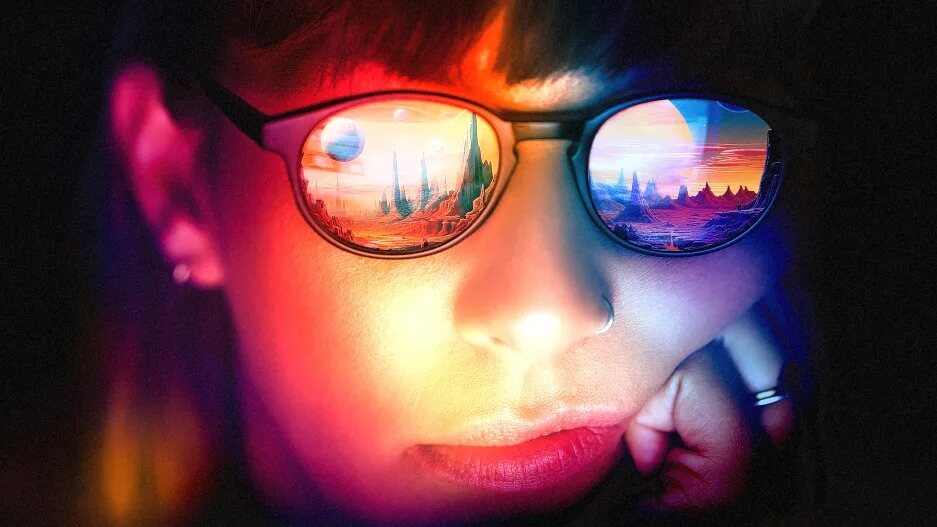

Generative AI is killing our sense of awe

If everything is extraordinary then everything becomes ordinary.

For all the talk about Terminators, lost jobs, and the end of reality, one of the most concerning things about generative artificial intelligence right here, right now, is how it can rob us of our sense of awe. In a world where every image can be extraordinary with a simple prompt, nothing can be truly extraordinary. It sucks the soul out of my socks.

I began noticing this phenomenon earlier this year, when certain photos started to trigger an instant feeling of “that’s probably AI.” Not the Pope rocking Balenciaga puffer coats or Trump getting arrested. I’m talking about images that are truly striking and believable: a shot of Turkey’s fairy chimneys in Cappadocia or these “martian mountains” in Iran. Most of my friends now feel the same instinct to mentally double-check if incredible photos are real or AI.

“People say these formations can’t be real,” photographer Aytek Çetin tells me of his majestic fairy chimney photographs. I thought the same thing: That has to be AI. Çetin assures me that his photos are very real; in fact, he organizes photo tours of the formations. “Everything about the Cappadocia is real,” he says.

Çetin’s photos grab your eyes out of your skull with their composition, subject matter, and exquisite execution. He says he edits them, but he never uses AI. “When editing a photograph, I usually dramatize the scene with light and shadow transitions, as well as making touches to increase the feeling of depth of field. I use focus stacking for maximum clarity,” he tells me. “But outside of these techniques, I do not add or remove any permanent objects that are not there at the time.”

His sensibility and technical virtuosity give his images that otherworldly AI je ne sais quois. AI’s ability to make the unbelievable believable—to turn anything you can or can’t imagine into visual perfection—seems to have retrained our brains to discredit the feeling of awe talented artists were once able to generate through their work.

This battle between the real and the synthetic prompted Nikon Peru to release an advertising campaign designed to reclaim the power of real photography. Titled “Natural Intelligence,” each ad shows an incredible image of something awesome behind a single line of text set in computer terminal typeface; a typical MidJourney ‘/imagine’ prompt poetically describes what you are seeing.

The image alongside the imagined prompt suggests that the photo is AI-generated, but a small block of text in the lower left corner tells you the truth: the name of the human photographer, the actual Nikon camera used for the shot, and the name of the place. On the right corner, is the slogan: “Don’t give up on the real world.”

It’s a good message—a reminder of the power of photography and the beauty of Earth. And yet, the ads feel bittersweet. Sad, actually. Because it’s also a perfect summary of how AI stole awe. Yes, the world is awesome. Yes, we can take photos of it. But AI could have made those photos and a million more with a single click.

DIMINISHING RETURNS

That “million more awesome images” is the problem. Because AI is capable of providing an infinite overload of visually stunning work, it makes everything—both the AI and the real photos—feel cheap and disposable. Our minds, connected to a constant flow of music, TV series, YouTube shorts, and TikTok videos, becomes numb and demands all forms of superlative: bigger, better, prettier, hotter, weirder, uglier, more shocking.

The speed and accuracy with which AI can produce shockingly good images has accelerated this trend. Not so long ago, people were likening Midjourney’s ability to conjure awesome images at random with the dopamine hits of “a slot machine for creativity.” Earlier iterations of Midjourney would produce a lot of trash but, for every 20 or so crappy images, there was one jackpot of perfection that combined aesthetics and subject matter in such an awesome way that it tickled synthographers‘ brain to the point of giggling out loud. “It’s the most addictive thing I’ve ever used, but I love it,” one user said in Reddit’s Midjourney channel. But when Midjourney 5 launched, it became so consistently good at delivering those jackpots that many of the same people started to complain they were missing the dopamine effect they once experienced.

Humans are wired to appreciate novelty. We want to be surprised. The scarcity of beauty is what makes it so compelling, and AI has shattered the concept of scarcity into perfect little shards. This is a problem, according to science. Awe is one of the fundamental feelings that makes us humans. It’s what made us ask ourselves about the world and develop science and culture, as described in a 2003 paper published in the scientific peer-reviewed journal Cognition and Emotion.

In that paper, psychologists Dacher Keltner and Jonathan Haidt spoke about the two things the human brain needs to experience awe. One is vastness, which is defined as the inescapable sense of witnessing something that feels larger than yourself and your regular daily grind. This vastness leads to the second factor, “accommodation,” as Big Think’s Kevin Dickinson explains in this column about our psychological need for awe.

“In psychology, [awe] represents the process by which people reevaluate their ideas or beliefs in the light of new experiences or information,” Dickinson points out. “In other words, when awestruck, people begin to question their world perspective and potentially shift it as a result. The power of nature or the beauty in human accomplishment, these things diminish our egocentric importance and that requires us to revise our understanding of the world and our place in it.” Without it, we wouldn’t be human.

Having a six-year-old, I witness awe in action every day. Driven by childhood’s natural curiosity—what Zen Buddhism calls shoshin, or the beginner’s mind—he finds marvel everywhere. As Keltner and Haidt describe, he is always revising his place in the world, growing, and understanding it and himself.

Last Monday, we went to see the world premiere of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, a restored copy of the legendary David Bowie concert filmed at the Apollo Hammersmith, London, in 1973. It was an awesome experience for him. I could see it in the way he looked to the screen, his eyes and mouth wide open as David Bowie “chameleoned” his way from “Hang On to Yourself” to “Rock’n’roll Suicide.”

The sense of vastness my child experienced was partially fact that he had never seen a concert. He had listened to Bowie many times at home, but he had never faced this fantastic experience on a giant screen, with thunderous sound enveloping him, a 20-foot Ziggy mesmerizing him with “Changes” and “Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud.” He’s still talking about it days later. For me it was amazing, but I didn’t feel his awe. I’m a tired old man who has already seen things a million times.

CAN WE RESCUE OUR SENSE OF AWE?

It’s extremely hard to keep our childhood sense of awe throughout our lives. Ziggy Startdust, the Moon landings, the first images of the James Webb Space Telescope, even AI itself—every awesome thing we witness eventually peters out in its awesomeness. It seems that, for most of us at least, our fate is to naturally become numb to the wonders of the universe as we experience them. So perhaps our failing sense of awe isn’t the fault of generative AI, after all.

And yet, it does feel like the rising stream of AI dreams is accelerating this process and killing our wonder faster than film, TV, or social media ever did. And it feels like there’s not a lot we can do to avoid this. We can consciously try to tune this out, yes. Be more strict with ourselves and our offspring. Limit our brain diet the same way we try not to eat (delicious) fatty food every day to avoid the total collapse of our bodies. Try to anchor our lives to the physical world and avoid the screens as much as we can. Be more present in the now and live less in an infinite number of virtual realities.

Sadly, looking at society’s recent failure with social media, fighting the AI imagery onslaught seems like a lost war for most of us. Maybe our saving grace is to try to tell those who are coming after us the history of our defeat so they can perhaps retain their sense of awe in some form. At least that’s what I’m trying to do with my kid: helping him to stay in the moment and go through life consciously focusing on keeping your childhood curiosity alive. If we can do that; if we can help the new generations avoid or delay the natural march toward jadedness, maybe we can regain our sense of awe ourselves by experiencing the world once again through their eyes.

That would be really awesome.