- | 8:00 am

How Rebag turned luxury bags into assets

Would you buy a used $40,000 bag? Rebag thinks people will. And there are signs that it is changing how luxury designers are running their businesses.

Last year, Telfar Clemens read a report that made him change his entire business.

The designer knew his logo-embossed totes were popular: They sell out within seconds of dropping online, and everyone from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to Beyoncé has been spotted with one. But when Clemens studied data from a 2022 report, which analyzed resale market, he discovered that secondhand Telfar bags go for nearly double their selling price, making them a better investment than Hermès or Chanel.

The report in question came from Rebag, a fast-growing startup that specializes in buying and selling luxury goods. Rebag stands apart from its competitors by arming consumers with data about the luxury market, creating a kind of Kelly Blue Book for high-end handbags so they can effectively treat these products like assets. This approach has worked well, allowing Rebag to grow quickly; fueled by $101 million in VC funding, it tripled its revenues during the pandemic. Now, as Rebag heads into its 10th year, it is not just influencing how consumers think about their bags, but also changing how designers and brands operate.

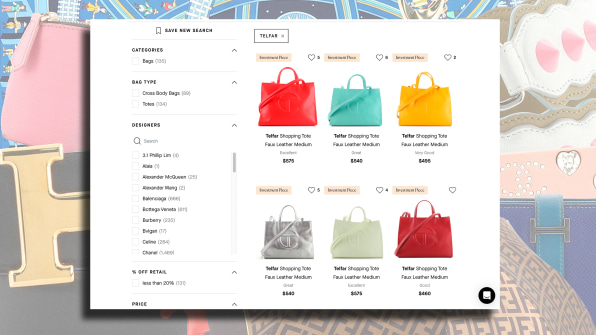

Take Clemens, for example. The designer’s goal has always been to create desirable products without making them prohibitively expensive. The Clair Report (named for Rebag’s app) proved that his plan was working: His totes, which are made from plastic, are priced affordably, between $157 and $250, and yet demand for them is sky-high, which is why they’re selling for upwards of $500 on Rebag.

But the report also made him worry that the steep resale value of the bags would make his brand be perceived as too pricey for the average consumer. So, this month, Clemens launched a new pricing model that drives down the price of his entire product range—and on his website, he points to the Clair Report to explain why he created this new system.

BRINGING TRANSPARENCY TO LUXURY BAG PRICES

Charles Gorra, Rebag’s founder and CEO, spent his early career as an analyst at Goldman Sachs and Rothschild before attending Harvard Business School, where he came up with the idea for the startup. When he surveyed the luxury handbag market, where bags can resell for thousands of dollars, it occurred to him that the value of these products was very opaque. “I want to know the resale value of every item I buy over $500,” he says. “From an iPhone to a car to an apartment. But with luxury bags, there was no real way of knowing.”

He launched Rebag in 2014, when the luxury resale market was just emerging thanks to recently launched companies like Vestaire Collective, TheRealReal, and Poshmark. Gorra set his company apart by focusing on the very highest end of the market; Rebag still only sells handbags from the 30 most in-demand designers, including Bottega Vaneta, Louis Vuitton, and of course, Telfar.

But perhaps the way Rebag truly stands out is that the company owns its entire inventory of luxury goods, rather than using a consignment model (like TheRealReal) or a building a marketplace (like Poshmark and eBay). Rebag has taken $101 million in VC funding and used it to acquire thousands of luxury products, including $40,000 Birkin bags and $15,000 Rolex watches. Gorra believed this approach would create a more seamless customer experience, because clients can buy and sell products on Rebag directly, without any middlemen.

But owning its inventory also means that Rebag has access to a lot of detailed information about luxury handbags, because the company actively sources products from individual sellers and auction houses. As a result, it has more detailed information about the supply and demand on the market than other players, like Poshmark and TheRealReal, which only gather data from their own users.

The brand has invested heavily in gathering this information and sharing it with customers. In 2021, it launched the Clair app, which uses computer vision and machine learning to enable customers to take a picture of a bag and instantly figure out how much Rebag will pay for it. The app’s technology assesses how old the bag is and its current market value, and the price offered is effectively binding; Rebag promises to buy it at that price if the company sends it in.

And Rebag also releases the annual Clair Report to arm customers with data about market trends, so they can make smarter buyer decisions. “We wanted to change the way consumers think of luxury goods from the moment they buy something in a boutique,” Gorra says. “We want them to think of resale first. They might choose to buy one Chanel model over another because they know it will retain more value.”

RESALE COULD DISPLACE NEW PRODUCTS

Gorra believes that creating price transparency around secondhand luxury goods is crucial to the growth of the resale industry, particularly at the higher end of the market. And indeed, experts believe that the secondhand market is on track to grow faster than global fashion industry. Research firm GlobalData found that the resale industry will hit $350 billion by 2027.

When he launched Rebag nearly a decade ago, his market research suggested that many luxury consumers were still hesitant to buy or sell products on the secondhand market because they weren’t sure they were getting good prices. Today, Gorra says that 60% of Rebag’s sellers have never sold a luxury bag before. “They’ve never sold anything, anywhere,” he says. “They’re entirely new to this market.”

In theory, if more consumers feel comfortable buying and selling secondhand luxury goods, more of these goods will circulate on the market—potentially displacing new products. This is better for the environment. Making a new Chanel bag requires extracting raw materials and generating plenty of carbon emissions. Buying a used one, on the other hand, requires no new materials and just enough carbon to ship the product to the new owner. But this shift won’t happen until luxury brands themselves embrace resale and begin changing their business models to manufacture fewer products. “Eventually, supply and demand will reconcile,” Gorra says. “The question is whether it takes five years or fifty.”

Gorra wants to nudge luxury brands in this direction. That’s why the company is building a “resale operating system” for buying and selling high-end products that other luxury brands could use. A brand like Gucci, for instance, could create its own branded resale site, so customers can buy and sell used Gucci products—and Gucci could take a cut, creating a new revenue stream for itself. “We have the ability to value items accurately and have the infrastructure to process individual luxury goods that come in,” Gorra says. “We can do this for our own brand, but we can do it for other brands, too.”

At the lower end of the market, ThredUp has already done this successfully, launching partnerships with dozens of brands like J.Crew and Kate Spade. Gorra believes Rebag is uniquely equipped to do something similar at the higher end of the market, with features that luxury consumers care about, like detailed pricing information and white glove service.

Gorra says that many luxury brands have been hesitant to jump into the resale market, possibly because they believe it will diminish the exclusivity of their brands. But things appear to be changing. In 2021, the luxury conglomerate Kering invested in the resale site Vestaire Collective. In January, Rolex launched its own pre-owned watch site. And earlier this month, Chloé launched a new system called Instant Resale that, like ReBag’s Clair app, will allow customers to upload product details to Vestaire Collective to receive an instant price and payment if they send it in. “Change appears to be coming to this industry,” Gorra says. “The question is whether it takes five years or fifteen.”