- | 9:00 am

A ‘sun umbrella’ attached to an asteroid? How this sci-fi solution to climate change would work

Solar shields are a decades-old concept. But this new iteration solves a long-time pain point.

With the accelerating pace of global warming, the Earth is set to warm by 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050, and up to 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100. In that scenario, oceans could boil, killing fish and decimating coral reefs. Severe heat would bring mass drought, make outdoor work intolerable, and turn a lot of land into desert that won’t sustain food cultivation. Millions would be forced to evacuate flood zones, as ice sheets melt and sea levels rise.

And we’re not cutting carbon emissions fast enough to stop those things from happening.

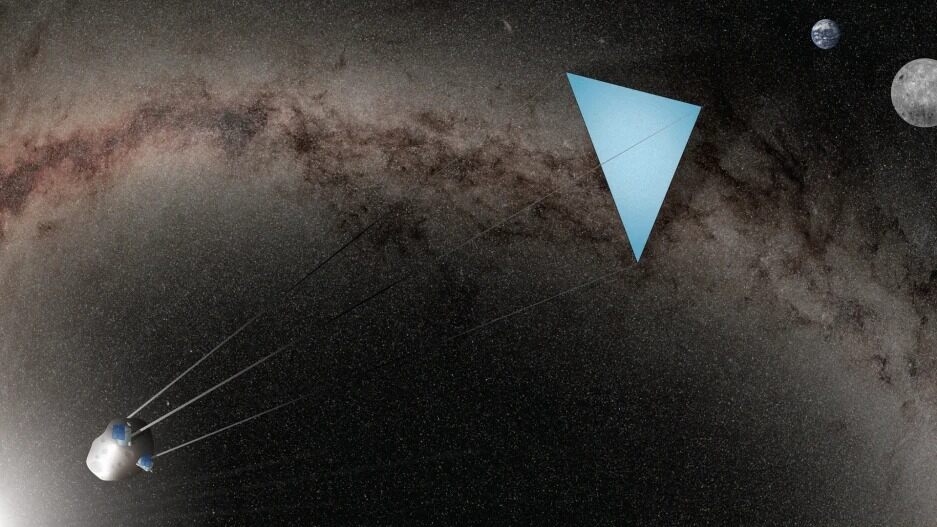

An astronomer from the University of Hawaii has an alternative for cooling the Earth. He’s designed the concept for a solar shield—to be planted in space and buoyed by an asteroid—to block some of the sun’s radiation from reaching the Earth.

The idea is decades old, but new findings make it potentially more practical and cheaper to achieve. Still, any real production is a long way off, especially given widespread criticism of such geo-engineering approaches.

The concept of “sun umbrellas” has been studied since 1989, with the idea that they could partially block the sun and thus keep some heat from reaching the Earth. “Effectively, putting less heat on Earth will cool it,” says István Szapudi of the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy, who published the new study.

But past research on such shields has encountered a consistent bug: weight. There’s an optimum location between the sun and the Earth where gravitational pulls of the two bodies reach equilibrium, such that an object will remain still. That makes it the preferred place for many satellites.

But placing a shield there means it would have to be extremely heavy, in order to offset the radiation pressure of the sun that would otherwise blast it away. It would need to be about 350 megatons in order to block out 1.7% of the sun’s light, which is the ideal number in order to return radiation to pre-industrial levels and prevent a catastrophic rise in temperatures. That huge mass makes it cost prohibitive and impossible to engineer.

Szapudi’s innovation solves this problem. It uses an asteroid as a counterweight, taking 99% of the mass burden, meaning the shield itself can be 100 times lighter. That’s crucial, because the shield is the only part that would need to be transported from Earth. The chosen asteroid, of course, would already be in space.

The project is still at a conceptual stage; much of the required technology is not yet available. Today’s rockets can only carry about 50 tons, far short of the shield’s required 35,000 tons. And we’re not yet producing enough of the preferred material, graphene, which is chosen for its light but strong qualities. Still, this puts the concept a lot closer than before. “The previous ideas were always science fiction,” Szapudi says. “With this idea, this now touches reality.”

The next step for Szapudi will be to work with university colleagues to use astronomical surveys to locate the best asteroids with regards to their size, location, and the least orbital manipulation. The study did not cover manipulation methods, or contingencies if the tether were to break.

Though it solves the weight issue, there are still many outstanding concerns from critics of geo-engineering, the term that refers to such large-scale manipulations of the Earth’s natural systems. Ethical considerations of modifying the atmosphere aside, it would be extremely hard to reach a global consensus, Szapudi admits. But he says it does offer a way to mitigate some of the harms as we try and dial down emissions. And, while curbing emissions alone won’t return temperatures to previous levels, this could cool the Earth to a desired point.

But it may also reduce incentives for businesses and individuals to curb carbon emissions. “Any geo-engineering approach, in my opinion, should be Plan B,” he says. Still, Szapudi thinks it’s worth considering given the urgency of the crisis. “Climate change is such a big problem that we have to consider every possible avenue to solve it,” he says. “This is one shot at it.”