- | 9:00 am

From cheese to steel: 6 unconventional ways that AI is being used to help the planet

From designing better batteries and materials to changing how steel is recycled, generative AI can help cut emissions in the fight against climate change.

Your first experience with generative artificial intelligence might have been via ChatGPT. But the technology can do much more than help you prepare for a job interview or write a bad poem. One particularly useful application: fighting climate change. Here are six ways that generative AI can help cut emissions, from designing better batteries and materials to changing how steel is recycled.

MORE REALISTIC FAKE MEAT

Eating less meat and dairy can cut emissions dramatically. To help persuade omnivores to forgo beef and pork, plant-based meat companies are trying to make products that look and taste like the real thing, and some are turning to generative AI to help.

A startup called NotCo uses a proprietary AI platform to generate new recipes for its plant-based products, searching through thousands of ingredients to match the texture and flavor of the animal version. Climax, a startup that makes vegan cheese, uses generative AI to help find the best ingredient combinations to improve qualities like the firmness of its prototypes.

BETTER EV BATTERIES AND GREENER FUEL

Batteries are the most expensive component of an electric vehicle, and they use materials like cobalt that cause environmental and social problems when they’re mined. As engineers work on alternatives, some are using AI. Chemix, a Bay Area-based startup, uses generative AI to design new battery chemistries based on data from tests. The company says that its system can design a better battery—avoiding cobalt, for example, or making batteries that can charge faster—in months instead of years.

Other scientists are using generative AI to help make clean fuels from electricity. David Rolnick, who leads a group at McGill University focused on how AI can tackle various climate-related challenges, is using generative AI to speed up the process of making catalysts used in green fuels.

“The goal is not to replace experimentation,” Rolnick says. “It’s to reduce the number of experiments you need. You’re never going to be in a situation where the computer designs something and you just build it without tests. But instead of testing a million things, maybe you have to test only a few.”

MORE EFFICIENT BUILDINGS AND BETTER MATERIALS

The climate impact of buildings is an “impossible problem of infinite complexity,” says David Benjamin, who leads applied research on net-zero buildings at Autodesk, the architectural and engineering software company. Buildings are responsible for as much as 40% of climate emissions, and the built environment is expected to double by midcentury—the equivalent of adding 13,000 new buildings every day.

“Incremental change and gradual improvements are totally inadequate,” Benjamin says. “So we need a completely new approach.”

An AI tool could learn from past projects. For example, if you’re building a large apartment complex near a busy road, it can consider how other buildings in similar settings dealt with air pollution. It could simultaneously look at how other buildings have been oriented to minimize extreme heat or cold, how windows were designed for ventilation, and multiple other factors that can make the building more efficient. Humans would always make the final decisions, but AI could make it easier to learn from past experience, not just at a single firm, but in architecture collectively.

Generative AI can also help speed up the development of new building materials. “If we’re going to make all these new buildings and reduce their carbon footprint, we’re going to need a lot of new materials—reusing materials, potentially using biomaterials, higher-tech materials that can lock in carbon,” Benjamin says. “I think in terms of making that kind of material innovation, again, there’s a lot of complexity, and there’s room for AI and generative AI to help with that.”

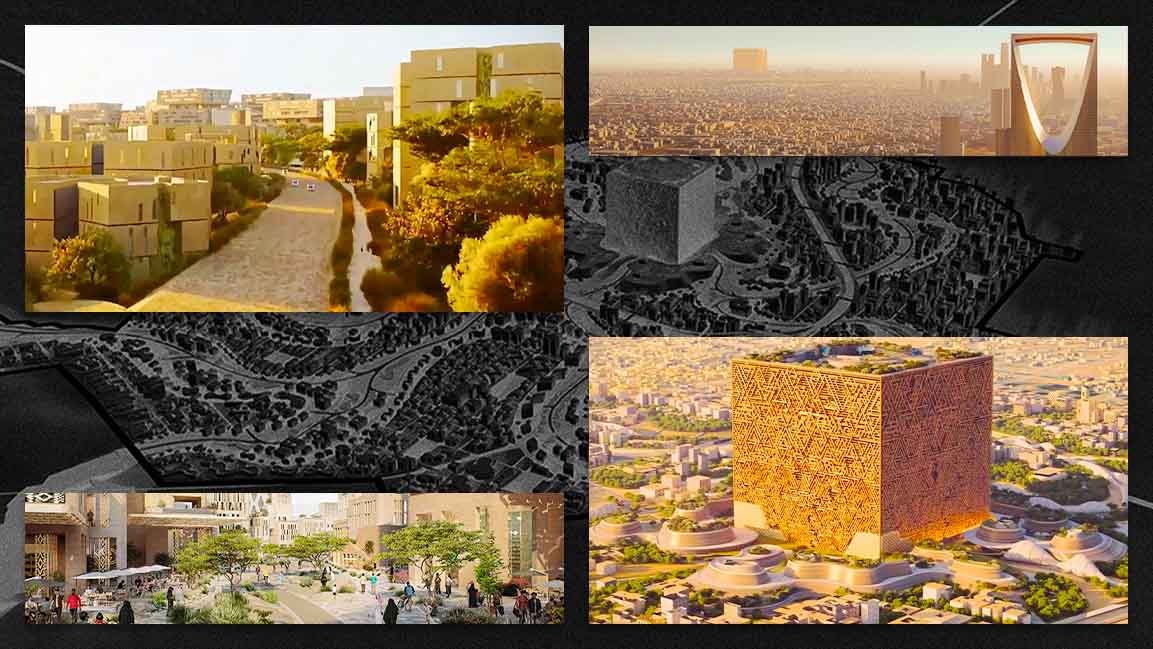

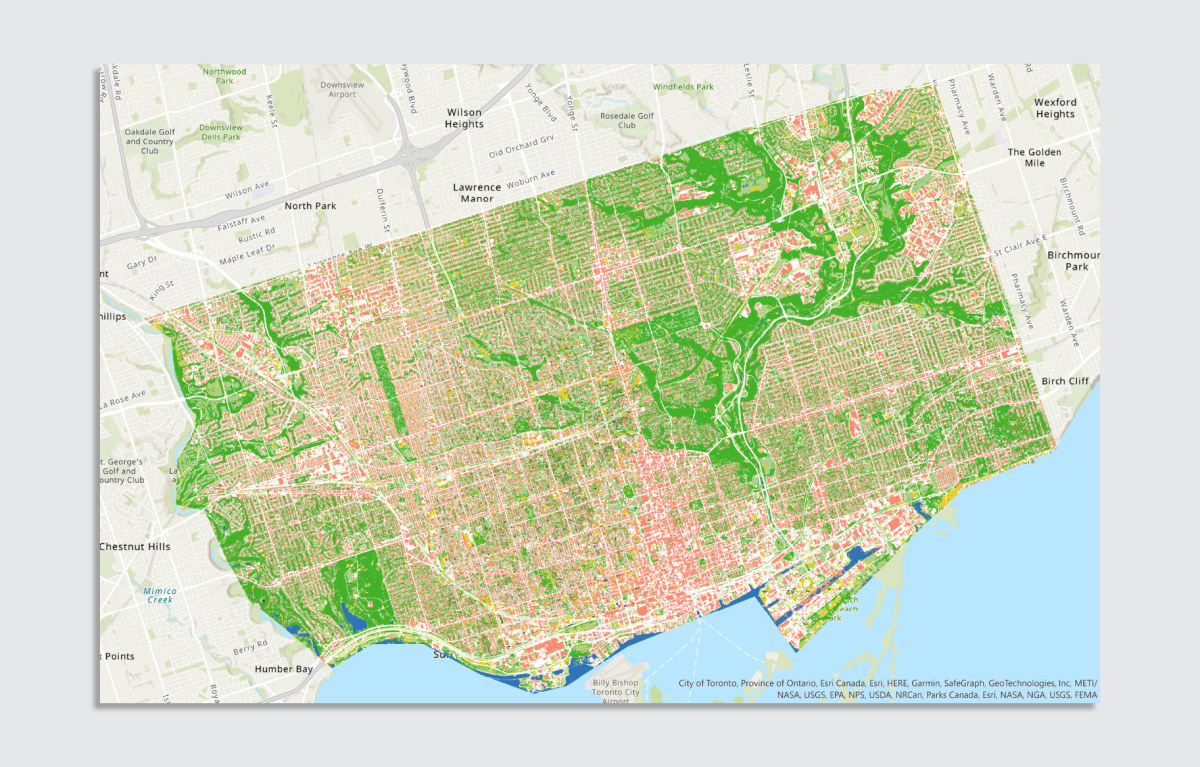

GREENER CITIES

In urban planning, generative AI could potentially be used to help find the best locations for infrastructure like EV chargers, or to suggest where to build a building to avoid climate hazards or to make it more likely that residents will walk more often, says Joe DiStefano, CEO and cofounder of Urban Footprint, a company that makes urban planning software.

Arup, the global design and engineering firm, says it uses generative AI to create detailed land use maps based on satellite images, making it possible to test different future scenarios for a neighborhood. (The company also uses AI to analyze how different design choices can affect extreme heat in cities, and to help identify where green spaces could be added to reduce flooding as storms become more extreme).

A CLEANER ELECTRIC GRID

Generative AI can be used to make “synthetic data”—data that’s realistic because it’s based on known parameters but avoids privacy issues because it’s not actually drawn from individuals. In the energy world, for example, smart meters collect useful data about when customers use energy, but that data often isn’t accessible because it’s private. AI-generated data can also be used to help manage the electric grid as more solar and wind power comes online and utilities need to manage how it interacts with power demands.

AI can be used for tasks like optimizing the design of power distribution grids, including suggesting the best route and size for power lines to make the grid as efficient as possible. Other types of AI can also be useful for the grid, including forecasting how much solar and wind power will be available. And even though utilities are often slow to change, “more and more energy companies are starting to look at these types of technologies,” says Franco Amalfi, sustainability portfolio lead for North America at the tech consulting firm Capgemini.

GREENER MATERIALS

Steel production is responsible for around 9% of global emissions, more than triple the pollution from the airline industry. While some manufacturers are racing to find alternatives for production—like a new Swedish factory from H2 Green Steel that will run on green hydrogen instead of fossil fuels—one startup is using generative AI to improve recycling.

“Recycling steel starts from scrap metal,” says Alp Kucukelbir, cofounder and chief scientist at Fero Labs. “Each batch of scrap is different: today some Hondas, tomorrow some old washing machines.” Operators typically blend old metal with larger amounts of virgin iron, which raises the carbon footprint of the final recycled material. However, the startup’s software uses AI to generate a custom recipe every 10 minutes, each time a new batch of scrap is processed, minimizing the amount of new material that’s used. Kucukelbir says that generative AI can also help enable circular manufacturing of other materials, like chemicals and cement.

Any use of generative AI should happen alongside human experts, says Priya Donti, executive director of the organization Climate Change AI and an incoming professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “I think it’s actually really important that you have an expert decision-maker who can indicate what it means for an output to be good and bad, rather than taking potentially low-quality output,” she says.

But there’s real potential for the technology, and Donti hopes that the current hype about it won’t distract from that. The boom in investing in generative AI “is not always informed by full knowledge of the technology,” she says. “One of my biggest fears . . . is that we’re going to lead to this hype cycle where there’s a ton of investments, and many things don’t work or are actively counterproductive or harmful, and then there’s a huge crash in a way that maybe hurts applications of AI to climate, for example. Having a principled understanding of what it can and can’t do is super important.”

It’s also important that it doesn’t create new sustainability challenges. By one calculation, training a medium-size generative AI model can use so much energy that it has a carbon footprint of 626,000 tons of CO2 emissions, or as much as driving a typical car more than 1.6 billion miles.

“We have to make sure that the technology is delivered efficiently, at low cost, and with the lowest possible power profile,” says Matt Wood, VP at Amazon Web Services, which wants to make generative AI easily accessible. Already, Wood says, the company is finding promising ways to shrink power use. That’s critical, he notes, because it wants to “put [generative AI] in the hands of every startup in every domain in every vertical and every country around the world so that they can apply it to some really difficult problems.”