- | 9:00 am

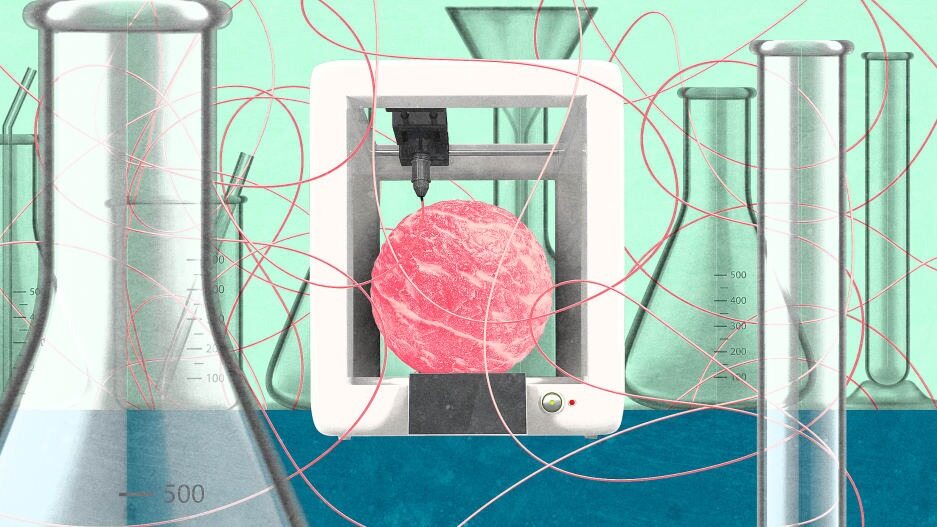

Hype built the cultivated meat industry. Now it could end it.

With lofty promises and missed benchmarks, many cultivated meat companies are in danger of looking more like Theranos than world-changing startups. How can the industry balance excitement with honesty?

As the founder of Reducetarian Foundation, a nonprofit organization focused on reducing societal consumption of meat, I’m of the belief that we’re never going to convince everyone to give up animal products altogether, so we need to come up with ways to fill that demand without destroying the planet. Cell-cultivated meat—meat grown from animal cells rather than slaughtered animals—could be one of those history-changing innovations, allowing us to feed the world without the dirty business of torturing animals.

So you can imagine my disappointment when Wired reported last month that all was not as it seemed at Upside Foods, a leading cultivated meat company in the U.S. Since the company launched in 2015, journalists have gushed about their promise to make cell-cultivated meat a reality. The prospect seemed practically inevitable, and even the world’s biggest meat producing companies were vying for a stake.

But contrary to what the company’s representatives were implying to the press, the story reported that they actually haven’t developed a scalable technology to create full-cut pieces of meat. The cuts they have served were made literally by hand, in a painstaking process that involves hours of skilled labor.

The fancy bioreactors at their California facility, the big promises of being able to scale “right away”—all of it was, according to the Wired report, little more than theater aimed at potential investors. The public statements were so far from the reality that some employees compared Upside to Theranos, the infamous health tech startup that collapsed when the technology never materialized.

But before we throw Upside in the bin with disgraced companies famous for selling nothing but promises, we need to consider the context. The venture capital funding process as it currently exists incentivizes exaggeration. Conducting research requires money, and money is acquired by dazzling investors with big promises. No dazzle means no money, no research, and no product, which encourages companies to stretch the truth in order to be able to develop the product or technology at hand. More than anything else, they’re selling an idea that pushes the limits of what we may believe is possible.

As a result, they set ambitious goals for themselves, and it’s these goals, not realistic timelines, that end up circulating in the media. Speaking to me during a site tour of their production facility in Emeryville, California, at the end of July, David Kay, Upside’s communications director, said, “we really wanted the first products out of the gate to set a high watermark . . . to be unambiguously delicious.” He was more frank with me than you would guess for someone whose company was about to be accused of as being less-than-upfront.

“The way these products are introduced to the world will really set the stage for how they are viewed . . . and so we really wanted to make sure we were starting off on the right foot, but the first products that will be available to large numbers of people will be the ground products,” Kay said, noting that their whole cuts “were not as scalable yet.”

As unrealistic as they may be, I find that founders and their followers tend to believe in their loftiest ambitions. The problem is that saying something will happen doesn’t necessarily make it so.

The comparisons to Theranos are certainly unflattering, but this strategy of a startup pretending to have made a technological breakthrough, or a founder deluding themselves into thinking they had—or soon will—in hopes of actually making that breakthrough before getting caught with one’s pants down, isn’t unique to these two companies. It’s just how fundraising works.

Consider Finless Foods, another cell-cultivated company. In 2017, their CEO Mike Selden was telling the press that while the first prototype of their lab-made Bluefin tuna cost something like $19,000 to produce, they “plan[ned] on” having price parity with typical Bluefin tuna by 2019. Four years after that deadline, this scenario has yet to materialize.

But it’s not necessarily dishonest to “plan” to achieve something and not succeed as quickly as you intended. To expect your per-pound production costs to shrink from $19,000 to $13 in less than two years is pretty unbelievable, yes. But when lots of people still find the whole idea of cell-cultivated meat pretty unbelievable, it’s not hard to see how realism and practicality could start to seem like no object.

In 2015, Peter Verstrate of Dutch cell-cultivated beef company Mosa Meat said he was “confident” that the company’s burger would be on the market in five years. It’s now been about eight years, and it still isn’t on the market. It’s debatable whether the problem here is purposeful misrepresentation for the sake of generating attention or self-deluded entrepreneurs who genuinely believe in their better-than-best case scenario projections. But in any case, Upside is far from the only company making bold claims that might be led more by optimism than by reason.

Is it possible to support innovation in cellular agriculture without feeding into the machine of hype—even if that means stretching the truth? All of the attention has undoubtedly served a purpose. With every startup pitching itself as the next big thing, a young brand needs to set itself apart as the best, and, importantly, the one that will be the fastest to turn a profit and deliver a ROI, in order to court investors. It’s not clear that these companies would have attracted the talent and funding they did had they been more aware or transparent about the status of their technology.

And if not for that talent and funding, it seems unlikely that they would have managed to develop even the technology that they do legitimately have, let alone the ability to keep developing ways to make whole-cut cell-cultivated meat. And if every cell-cultivated meat startup hits the same roadblocks—if none of them can attract investors with a grounded and realistic look into their work—that means none of them get to work on this potentially world-changing technology.

At the same time, it’s possible that all the buzz these companies, including Upside, have worked to cultivate will have backfired. For one thing, the matter of consumer trust is of particular importance, even more so than with any other consumable product, because to many, cell-cultivated meat is still a strange, new, and not particularly appetizing concept.

If consumers start seeing cell-cultivated meat companies as blatantly dishonest, they’re putting an already-precarious product on pretty shaky ground. The reputational damage might even bleed into other alt protein sectors, like plant-based meat, making it more difficult for companies like Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat to build a customer base as well, killing—or at least slowing down—any possibility of these new technologies changing the food system in any significant way.

And staying silent about any of the problems that are keeping cell-cultivated meat from coming to market is not going to help the industry at large solve them. On my recent visit to San Francisco, I met the people behind several cell-cultivated meat brands (including Upside’s) and got to try some of their products. Josh Tetrick, CEO and Founder of Good Meat, another of just a handful of cell-cultivated meat companies to earn regulatory approval in the U.S., made some salient points about the process of scaling.

Once you have a small facility and regulatory approval, he says, “then you are faced with the reality of, okay, what does a large scale facility look like? And then you’re faced with the reality of not just modeling it in a room, but actually going out and getting real quotes from real suppliers and doing real site visits, and then reality hits you in the face even more,” as things reliably turn out to be more expensive and time-consuming than even your safest estimates.

But, he says, “that doesn’t mean that suddenly we don’t want to do this, it just means we are a bit closer to the truth of it, so we can better deal with it as opposed to living in a fantasy land.” It requires time and resources both to ignore or cover up a problem and to try fixing it—but only the latter might actually result in finding a permanent solution with which to move forward. Or as Tetrick put it, “sometimes, if you’re trying to do something so urgently, you can sacrifice the probability of it happening in the longer term.”

Regardless of what exactly happens with Upside, I predict that this moment will mark a shift in the way cell-cultivated meat startups present themselves. The best way I can characterize my recent experience in San Francisco, touring the who’s who of cell-cultivated meat, is . . . varied. Some of the brands used the sort of fluffily optimistic, “the future is here” language, while others were more candid about the industry’s challenges. Some made hard sells on products that supposedly taste just like the real thing (only one of them did, though the texture was a bit lacking), while others readily admitted that if they wanted to compete with conventional meat, they had a ways to go.

I think it’s fair to suspect that if everyone’s fraud detector is on high alert after a few negative stories, it’s going to be the humbler, less flashy brands that earn trust from both investors and consumers. It’s a good reminder that any sales pitch that seems too good to be true probably is. We have a lot at stake here, both financially and in terms of our future on this planet. We would be smart to place all of that in the hands of innovators who practice transparency and honesty, even when the truth might hurt the sale, because the climate crisis is going to be a global issue for far longer than just until next quarter.