- | 9:00 am

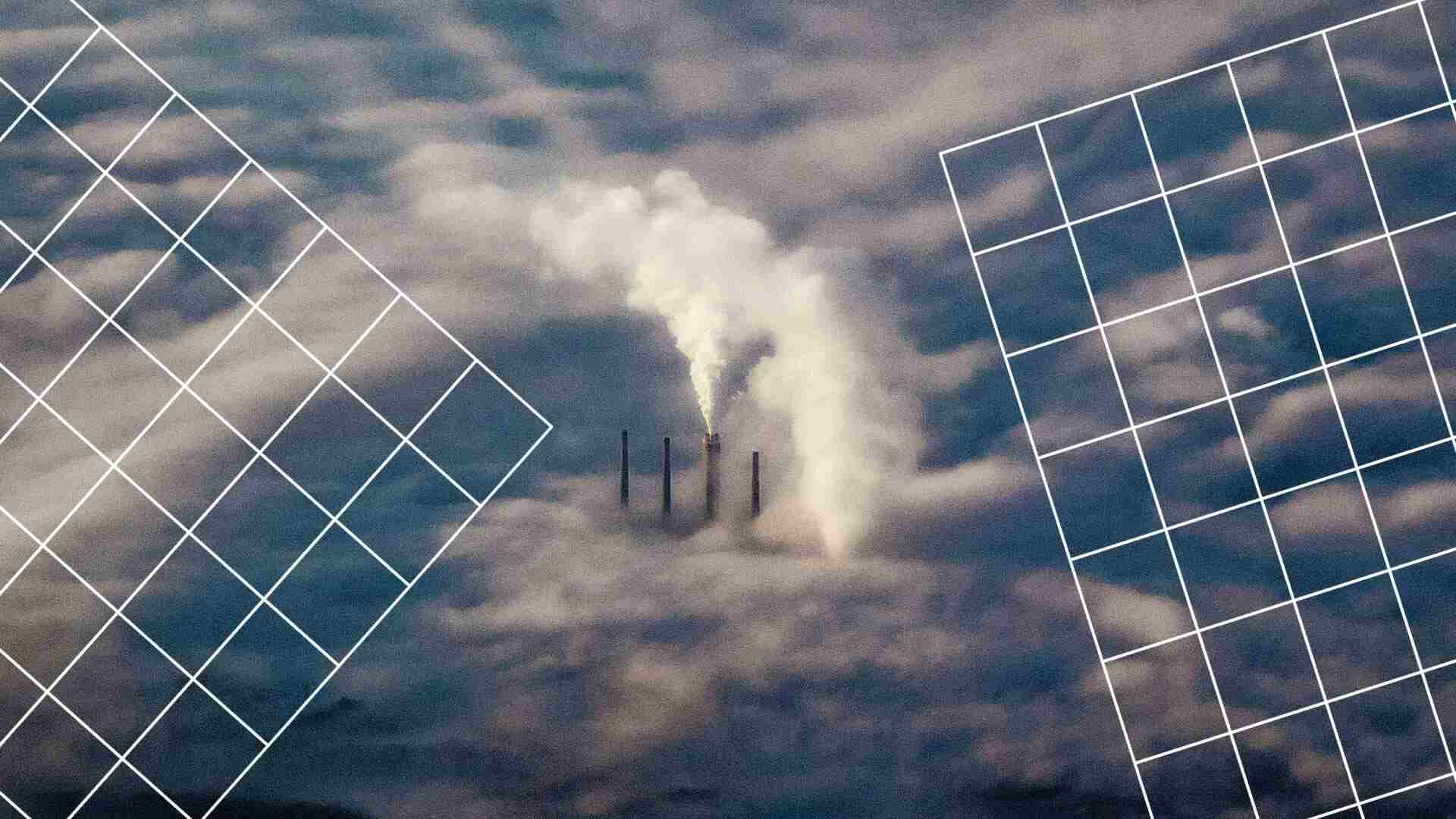

In 2009, 34 countries set emissions reduction targets. More than half failed

At COP15 in Copenhagen, 34 countries pledged to reduce emissions by 2020. Here’s why most struggled to hit their targets.

At the 2009 UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, more than 30 countries pledged to reduce their emissions by 2020. But many didn’t reach those goals: Out of 34 such pledges, 19 countries failed to fully meet their climate commitments, according to a new study.

At that conference, also known as COP 15 Copenhagen or the Copenhagen Summit, the world didn’t reach a global climate agreement. (The Paris Agreement, which set ambitious global goals to curb pollution and limit global temperature rise, was adopted at COP21 in 2015.) Still, individual countries set their own goals, which varied widely. The United States, for example, pledged a reduction “in the range of 17%” compared to 2005 emission levels; Croatia aimed to reduce emissions by 5% compared to 1990 levels; and Norway pledged a 30%-40% reduction relative to 1990 emissions levels.

In a study published today in the journal Nature Climate Change, researchers from University College London looked at the 34 goals set in 2009 that included emission reduction targets with a clear timeline. They calculated a country’s total carbon footprint by tracking “consumption-based” emissions, which includes emissions from activities within a country’s borders as well as the carbon footprint of goods that are manufactured abroad and then imported.

Of those 34 pledges, 12 countries failed to meet their goals at all: Australia, Austria, Canada, Cyprus, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, and Switzerland. Seven countries were part of what the researchers called the “halfway group,” meaning they decreased their emissions, but did so by outsourcing emissions to other countries. This sort of “carbon leakage” essentially undermines efforts to reduce global emissions levels and increases pollution in those countries to which emissions are outsourced. The “halfway group” included Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Luxembourg, Malta, and Poland.

Fifteen countries met their climate goals in terms of both the territorial emissions within their borders and their consumption-based emissions. Those countries were Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greeze, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Because every country had different climate goals, and because they also started at different points (in terms of how efficient their current technologies were, for example), their climate journeys were difficult to compare. But the researchers did find a few commonalities. For countries that weren’t able to meet their emissions goals, the biggest driver was a rising GDP per capita, as well as population growth. As these economies grew, they used more energy—and even if that country was able to increase its energy efficiency, it still wasn’t enough to reduce emissions. (Economic growth has long been tied to rising emissions, but some places are showing that it’s possible to decouple the two.) For countries that met their goals, ramping up clean energy—and transitioning away from coal power—was key.

The researchers say this is the first effort to gauge how well countries met their reduction pledges from COP15. Though the Paris Agreement goals supersede those made in Copenhagen, these results could still signal how likely countries are to meet other climate goals. “Our concern is that the countries that struggled to reach their commitment from 2009 will likely encounter even more substantial difficulties reducing emissions even further,” lead author Jing Meng said in a statement.

The study also highlights the challenges for a country to reduce its emissions while growing its economy. This puts the onus on richer countries to be climate leaders—and to mitigate that “carbon leakage” that can cause another country’s emissions to rise. “Rich countries have neither done enough, nor pioneered roles in climate mitigation,” senior author Dabo Guan said via email, “which must start now without any excuse.”