- | 9:00 am

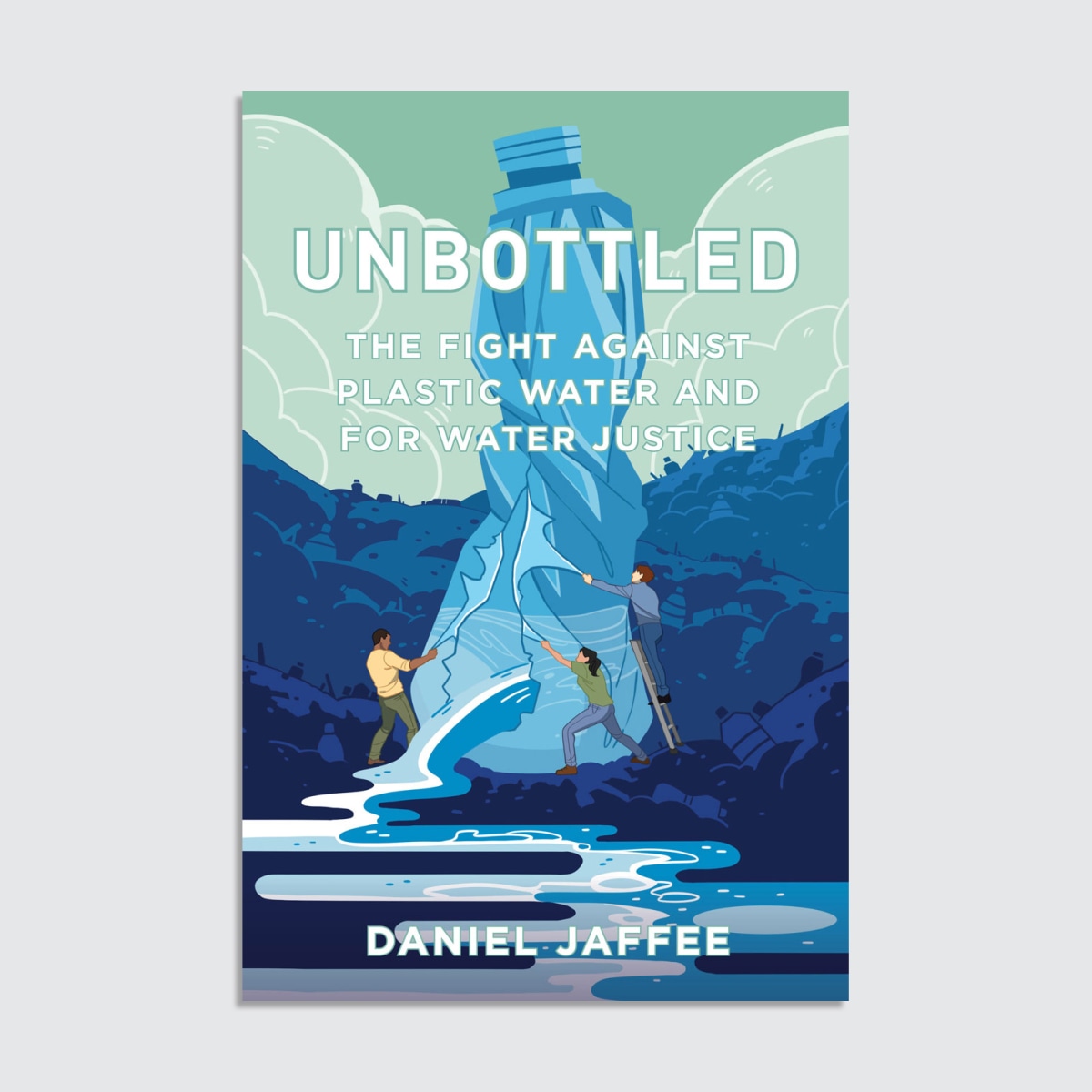

The twisted story of how bottled water took over the world

In his new book, ‘Unbottled,’ author Daniel Jaffee explores how bottled water’s meteoric rise has exacerbated inequality and intensified pollution.

How did the nascent bottled water industry make a market for a product that for much of the past century was largely viewed as an unnecessary or wasteful luxury good? In just four decades, this commodity has transformed into a ubiquitous consumer object that is now the primary, and sometimes sole, source of drinking water for billions of people globally.

The story of bottled water’s resurgence in places with abundant, clean tap water revolves around the question of why people have increasingly come to distrust their tap water, and how the expanding bottled water industry has fueled and taken advantage of this phenomenon.

AN INDUSTRY APPEARS: THE BIG FOUR AND MORE

The effective start of the modern American bottled water industry occurred in 1978, the year Perrier launched its bottled water brand in the United States with a massive advertising campaign.

Many wondered why people would spend good money for a bottle of imported spring water when they could get perfectly clean water straight from the tap. But critics underestimated the power of snob appeal. “Perrier,” writes branding expert Douglas Holt, “pioneered the idea that drinking bottled water in small single-serve glass bottles was an affordable way to grasp a bit of European sophistication, which resonated among so-called yuppies.”

Perrier’s success changed the game. At the start of the 1980s, the North American bottled water industry consisted almost entirely of local and regional spring water companies, many family-owned. But once consumption began growing by double digits, national and global brands started snapping up these bottlers. By 1988, only 10 companies controlled over half of the U.S. market.

At the forefront of this buying binge was Perrier. In 1992, Perrier, in turn, was acquired by Swiss-based Nestlé, the world’s largest food and beverage corporation. Groupe Danone, a French conglomerate best known for Dannon yogurt, brought its Evian and Volvic waters to North America and acquired several Canadian bottlers. By the turn of the century, Danone, Nestlé, and the Japanese firm, Suntory, together accounted for half of U.S. bottled water sales.

During the 1990s, this market underwent another upheaval: the entry of giant soda makers Coca-Cola (with its Dasani brand) and PepsiCo (with Aquafina). Holt writes that because these competitors “controlled the key distribution channels . . . they could easily wrest control of the category simply by delivering the convenience that drinkers demanded. And that is what they did.”

These soda giants not only had existing distribution networks and bottling plants. They also enjoyed ready access to a cheap, abundant supply of their prime ingredient: the same refiltered municipal tap water that they already used in their other beverages. This was an entirely different proposition from that of their competitors, whose bottles at the time contained groundwater from springs or wells.

Brian Ronholm of Consumer Reports argues that “these bottlers are essentially double-dipping—receiving low-cost water subsidized by taxpayers and then turning around and selling it back to the public at a significant markup.” The share of U.S. bottled water that comes from public tap water systems soared from one-third in 2000 to almost two-thirds in 2017.

HOW THE INDUSTRY MADE A MARKET

Why do consumers purchase bottled water, or how have they been persuaded to do so? Ultimately, it boils down to five key factors: fashion, flavor, fitness, frequent drinking, and fear.

The simplest to address is fashion. It’s undeniable that many consumers drink bottled water, or select particular brands, because of the perceived cool factor. While bottled water firms pay for celebrity endorsements and product placement, they also get plenty of free star validation anytime a celebrity is photographed with a bottle. President Obama appeared publicly with bottles of Fiji Water, a priceless promotional gift. More recently, Dwayne Johnson and Gwyneth Paltrow have partnered with bottled water brands.

Second, market research shows many consumers buy bottled water because they don’t like the taste of their tap water. These perceptions may be a result of consumers’ repeated exposure to bottled water—particularly the standardized, bland flavor of the re-treated tap water that constitutes most bottled water in the United States today. These brands use hyperfiltration, UV light, and reverse osmosis to strip out chlorine and minerals that impart taste to water. Then to make it palatable, they add proprietary mineral blends, known colloquially in the industry as “pixie dust.” This trains people to expect a generic taste from drinking water. And once trained, such preferences are very difficult to reverse. However, in blind taste tests, the tap water in many cities frequently wins out over bottled water, suggesting the role that branding and packaging may play in perceptions of taste.

Third, the promotion of bottled water as a means of attaining health, fitness, vitality, and youth leverages a long and deep tradition in advertising and marketing. “To sell bottled water as a lifestyle choice,” sociologist Andrew Szasz writes, “advertising associated it with images of desirable social identities, being young, fit, attractive, and active.” Industry marketing also tapped into broader societal concerns about health in the 1990s and 2000s—including the role of soft drinks in growing obesity rates.

Fourth, beginning in the mid-1990s, the bottled water industry began promoting its product as a solution to an ailment that had only recently been “discovered”: a chronic lack of hydration, for which drinking eight glasses of water per day was alleged to be an essential remedy. While many scholars argue this idea is a myth, a culture of “frequent sipping,” and carrying bottled water at all times, emerged.

FEARING THE TAP

In Merchants of Doubt, by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, the authors quote a 1969 internal memo from an executive at tobacco firm Brown & Williamson: “Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the mind of the general public. It is also the means of establishing a controversy.”

While the cigarette makers protected their sales and fended off lawsuits for decades by sowing doubt about the health harms of their product, doubt can be deployed in many ways. The bottled water industry has both subtly and overtly spread doubt about the safety of public tap water, positioning its product as the safer alternative. In what some critics have called a “war on tap water,” individual bottled water firms and industry groups have impugned the quality of public drinking water.

Many people, of course, do not need to find incontrovertible evidence of health risk in order to lose confidence in their drinking water supply; mere doubt about the trustworthiness of tap water is sufficient. In one of the most widely reported examples of this strategy, Fiji Water ran a full-page ad in national magazines in 2006, with the caption, “The Label Says Fiji Because It’s Not Bottled in Cleveland.” Subsequent tests, however, showed that Fiji Water contained volatile plastic compounds, high levels of bacteria, and arsenic, while Cleveland’s public water supply was far cleaner. Royal Spring Water ran an advertisement that proclaimed, “Tap water is poison.” And a current online advertisement for Primo Water depicts a corroded pipe and warns consumers, “Your tap water could be full of harmful bacteria and contaminants.”

Do these efforts to cast doubt on the quality of tap water work? In a word, yes. Since the 1970s, opinion polls have shown a major decline in public trust of tap water quality in the United States. The proportion of Americans reporting they were extremely concerned about drinking water pollution rose from 32% in 1973 to 66% in 1988, and it has since risen as high as 80%.

Studies find a strong correlation between people’s perceptions of poor tap water quality and higher bottled water consumption. Whether these perceptions correspond to the actual safety of the tap water is another question. In a vicious cycle, argues Szasz, the embrace of bottled water reduces pressure on government to maintain public water infrastructure, which can imperil tap water quality, further weakening trust, and accelerating the shift to the private solution of bottled water.

AN UNFAIR FIGHT

In this way, the war on tap water is effectively a war on public water utilities. Faced with such a threat, why don’t those utilities fight back? Some have—for instance, Cleveland’s water department pushed back against the Fiji Water campaign that impugned its tap water. Yet in this competition, most public water utilities are vastly outmatched in both budget and influence by private companies.

Most water utilities in the global North are nonprofit, public agencies under local governments, staffed by highly trained civil servants, biologists, chemists, engineers, and administrators, among others. Their imperatives are to protect public health, maintain ultra-high-quality water, ensure consistent delivery, and keep rates reasonable. Their job descriptions don’t include profit maximization, and they’re not typically trained to actively market their “product” or defend it in the media.

There’s also the prospect of legal action. In his book, Bottled and Sold, Peter Gleick writes that after Miami-Dade County, Florida, ran radio advertisements in 2008 promoting the county’s tap water as cleaner, cheaper, and safer than bottled water, the nation’s top bottled water firm threatened a lawsuit. The mere threat of such costly lawsuits may have a chilling effect on similar efforts by other cities to promote tap water.

Of course, public agencies shouldn’t have to compete against a well-heeled global industry, but the dramatic shift toward bottled water and the ensuing decline in tap water consumption threaten a core government service. Water utilities will need to enter the battle over public perception and communicate to residents that tap water is not only far more affordable and environmentally sustainable than bottled water but in most cases as safe or safer.

HOW SAFE IS BOTTLED WATER?

In the United States, the story of bottled water safety is one of an industry governed by different and largely weaker regulations than those that apply to tap water. Municipal tap water in the United States is regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Bottled water, on the other hand, is deemed a foodstuff and thus is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration.

The difference between EPA and FDA regulation is effectively the difference between night and day. Author James Salzman sums up the distinction: “If contaminants are found in tap water, which is tested daily, the water utility must quickly inform the public. If contaminants are found in bottled water . . . manufacturers must remove or reduce the contamination, but there is no similar requirement to notify the public. Perhaps most important, FDA regulations only apply to goods in interstate commerce, i.e., traded across state lines. Yet anywhere from 60% to 70% of bottled water never enters into interstate commerce. As a result, two-thirds or more of bottled water is effectively exempt from federal regulation.” Most large public utilities actually test water safety far more than daily. Washington, D.C., for example, tests its drinking water 30,000 times per year.

FDA regulators inspect bottling plants but do not test the actual water themselves, leaving that to manufacturers. The number of FDA bottled water inspections fell by one-third between 2008 and 2018. Incredibly, even when water is found to be contaminated, “in most cases manufacturers don’t have to stop bottling or alert the public,” according to Consumer Reports.

In other words, if you don’t actively look for contamination, or don’t have the staff to do so, you probably won’t find it, and consumers won’t know about it. A 1999 study of over 100 bottled water brands by the NRDC found that 33% either violated a state standard or exceeded purity guidelines for cancer-causing chemicals or arsenic. A 2008 analysis of 10 major bottled water brands in the United States uncovered 38 pollutants, including arsenic, bromates, and trihalomethane.

More recent reports document a troubling pattern of ultra-light-touch regulation. For example, a series of investigative articles by Consumer Reports, some copublished with The Guardian, found high levels of arsenic in Keurig Dr. Pepper’s Peñafiel water brand. Consumer Reports later found that the FDA had been aware of this fact since 2013 but didn’t act.

In sum, public water utilities are operating on an unfair playing field against the bottled water industry, which escapes most of the scrutiny to which they are subjected. The industry is largely allowed to police itself and is in effect shielded from most negative public revelations. Thus consumers have little chance of learning when bottled water is found to be contaminated or is recalled. “Assuming bottled water is safer than tap water may make us feel better,” writes Salzman, “but there is little reason to think this is necessarily so.”

Edited excerpt from Unbottled: The Fight against Plastic Water and for Water Justice, by Daniel Jaffee, published by the University of California Press. ©2023