- | 9:00 am

A new tech rebellion is taking shape. Here’s what the Luddites can teach us

Two centuries ago, the Luddites revolted against an unjust technological disruption. In an excerpt from his book, “Blood in the Machine,” Brian Merchant reminds us how tech uprisings begin

It was 1811, and a young cloth dresser in Huddersfield, England, was worried. There were the breakneck evolutions of relentlessly accelerating technologies, the harsh politics of inequality, the privatization of industries, and the tail end of a smallpox pandemic. But as mill and factory owners installed new textile machines—the water frame, the power loom, the gig mill—George Mellor was now seeing his working identity stripped from him: seven years of training pronounced worthless. “There’s a conspiracy on foot to improve and improve,” he is imagined by historians to have said, “till the working man that has nothing but his hands and his craft to feed him and his children will be improved off the face of creation.”

Within months, Mellor would join the growing movement of workers known as the Luddites, who, lacking other ways to oppose their bosses’ new cost-saving machines, began raiding factories at night and destroying them.

The notion that textile workers like Mellor would worry about losing their agency to machines in the early 1800s, when the machinery in question was a wooden, water‐powered loom, may strike us as implausible. Our twenty‐first‐century visions of displacement by machines, after all, concern omniscient artificial intelligences and sleek autonomous robotics. But his concern was colored by deeper anxieties, too—what is the value of human labor, they wondered, or even human life, in a world where technologies seem constantly poised to replace us? In fact, it’s remarkably similar to debates we’re still having two hundred years later, in books like Rise of the Robots, film franchises like Terminator, and cable news segments about the looming AI takeover.

“I honestly feel like a master sock weaver at the start of the Industrial Revolution,” wrote Will Butler, a musician whose earnings have been eroded by Spotify and other streaming platforms using technology that superseded CDs and download purchases as the dominant way that people listen to music. Spotify pays artists an average of $0.004 per stream. “People will still get their socks, maybe worse than the ones before. And in the end, technology will plow us over.”

“It’s not only rideshare drivers whose families are starving,” said Marie Harrison, a seventy‐two year‐old Uber driver at Airport Park, outside LAX, where she had gathered to strike in protest of poor working conditions in the summer of 2021. “What’s happening is a disgrace. They’ve put us back, these large corporations, to the 1800s, when people were begging — begging to be paid for the hard work they do.”

The reason that there are so many similarities between today and the time of the Luddites is that little has fundamentally changed about our attitudes toward entrepreneurs and innovation, how our economies are organized, or the means through which technologies are introduced into our lives and societies. A constant tension exists between employers with access to productive technologies, and the workers at their whims. Clearly such tension does not always lead to violent insurrection. But then there are people like George Mellor.

So, how do uprisings against Big Tech and the machine owners begin?

When entrepreneurs and executives deploy new technologies intended to replace skilled work, confound or elude regulations, or degrade traditional jobs en masse—especially in difficult economic circumstances. It’s worse if those workers have no recourse.

When technology has eliminated or degraded a worker’s job, status, or identity; when it is hard or impossible to organize to negotiate outcomes; and when support is inaccessible—well, we might expect just about anyone to feel cornered, angry, and more apt to turn to desperate measures. Obvious? Perhaps! But you wouldn’t know it from how U.S. policymakers have approached gig work, automation, and workplace surveillance in the twenty‐first century. As in the Luddites’ day, policymakers happen to be actively benefiting from the largesse of today’s technological elite—the deep‐pocketed Silicon Valley campaign donors and “job creators.” Too many leaders have turned a blind eye to the outcome; they, too, it seems, would sooner send in the National Guard than intervene in a meaningful way to stanch the bleeding.

None of this necessarily means that American workers will suddenly start smashing the machines that are executing their exploitation, though it does mean they will sometimes channel that anger at the politicians, or direct it at “others” and outsiders: immigrants, minorities, political opponents. A Brookings Institution study found that in regions where populations experienced a higher rate of automation, voters turned out in higher numbers for Donald Trump in 2016. Trump’s rhetoric was tailored to stoking resentments over all of the above into anger, as he promised to restore America to its former, preautomated industrial glories. “Automation perpetuates the red‐blue divide,” the Brookings survey concluded.

Opaque and circuitous supply chains, decades of offshoring, and other hallmarks of a globalized economy have conspired to cloud the precise causes of any given worker’s sense of exploitation. George Mellor could see William Horsfall’s factory, with its automated gig mills, looming on the outskirts of Huddersfield; today’s workers see the empty storefronts and idled auto plants, but less often the new factories where robots are supposedly performing their labor. It’s harder to smash a machine if it’s nowhere near you, or if it’s invisible—if, say, it’s ubiquitous lines of code. This confusion is one explanation for why we’ve seen less aggressive worker action against major employers in general over the last decades; the targets of opprobrium are cloaked in the complexities of global capitalism, so the anger has been diffuse. But the modes of the modern factory owners’ exploitation are becoming clearer to workers again, and the possibility for more Luddite‐like targets remains very real.

As San Francisco was gentrified by tech companies, displaced renters and residents facing eviction blocked the route of the notorious Google Buses, forming ad hoc protests and hurling rocks at the vehicles. We’ve seen how drivers in France reacted when Uber entered its market—with riots and the Luddites’ proverbial hammer of Enoch. And a new generation of self-identified Luddites point to the targeted vandalism at the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020 as examples of strategic retribution for economic grievances.

Meanwhile, governments have exacerbated matters by implementing punitive policies that restrict workers’ rights. In the Luddites’ day, Parliament instituted a bloodier and harsher set of laws, to be sure, but a similar logic, as far as who gets protected and who gets punished, drives the American economy today. Tech companies and their allies in government are striving to prevent contract, gig, and part‐time workers at Amazon, Uber, and beyond from organizing. Executives are cutting off their workers’ only chance at recourse when it comes to how technology is deployed in their workplaces. The workers are deprived of options and protections, even at moments when they might appear to have some leverage. “The American economy runs on poverty, or at least the constant threat of it,” New York Times columnist Ezra Klein wrote in 2021. “The barest glimmer of worker power is treated as a policy emergency, and the whip of poverty, not the lure of higher wages, is the appropriate response.”

When the social norms and customs foundational to working people are systematically undermined by those wielding technologies new or old.

Just as the Luddites’ actions were a response to the ways that entrepreneurs were shaping the advent of the factory system—and as people have periodically protested automation and the deepening of that system in the centuries since—workers today are feeling the strain at on‐demand app companies like Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash, not to mention those relegated to doing what labor scholar Veena Dubal has called digital piecework.

If any current group’s situation most closely resembles that of the Luddites, it is the large and ever‐growing cohort of gig workers whose backs are against the wall, their options diminishing daily. Many of these are skilled workers who were once better‐compensated, like the New York City yellow taxi drivers upended by ride-hailing apps; many others have lost benefits and protections, or at least predictable wages and work schedules. Their lives have been disrupted, and now their work regimes are dictated by often inscrutable algorithms that make them compete against one another for every gig.

This new generation of algorithmically arranged, precarious work structures is permeating even more of the economy—it’s already happening to lawyers, writers, emergency responders, even security forces. And the rise of generative AI services stands to accelerate the process. There’s likely no bigger sign of that acceleration than the ongoing writers’ and actors’ strike. The longest of its kind in history, the standoff in Hollywood is a bellwether, underscoring the hunger that executives have for automating even creative work, and the lengths to which their workers will go to have some say in that disruption.

But unlike the writers and actors, not every worker has the protections of a union; fewer and fewer do. Right‐to‐work laws make organizing much harder, and measures like Prop 22 prevent gig workers from finding stable employment, receiving benefits, or forming a union. Uber and Lyft can change their rates at their whim. The 9‐to‐5 American dream, with benefits and a retirement pension, is being disassembled, destroyed, deconstructed—and romanticized today in a way that preindustrial weaver and cropper life was in the early 1800s. The Luddites fought to protect a lifestyle that they recognized, that was tradition‐bound, that let them spend time with their families and maintain their autonomy. More workers today are finding themselves motivated to fight to protect those things, too.

When the perception that the entrepreneurial elite have been overcome by greed and self-interest becomes conventional wisdom. When workers see that tech titans are openly willing to profit even while others suffer.

Anger at money‐grubbing robber barons is one of the most time‐tested forms of class rage; when it becomes clear that those barons are using a new technology to further exploit their workers, that rage stands to be amplified—and to find a target in said technology. The Luddites wrote their letters to entrepreneurs and factory owners, to the local magistrates who sheltered them, and occasionally to the Prince Regent and his ministers. It was obvious who was acting immorally (and illegally) and who was responsible for perpetrating the new mechanized industrial regime that was putting them out of jobs and reshaping, against their will, the norms and customs that made their lives worth living.

Elon Musk was widely admired, even in liberal circles, until he began vocally opposing a unionization effort in his Tesla factory. He bought Twitter, fired half its staff—thousands of tech workers—and became the most divisive figure in tech. Amazon warehouse workers continue to organize around the long shadow of Jeff Bezos’s brutal and mechanistic work policies. Opinion polling from Gallup has shown that Mark Zuckerberg is disliked more than the company he runs. A growing number of billionaire founders have become engulfed in scandal, accused of fraud and malfeasance: FTX’s Sam Bankman‐Fried. Theranos’s Elizabeth Holmes. The list goes on. There is an animosity towards specific Silicon Valley elites that has only intensified in tandem with the expansion of their power.

When managers use technology to embark on the widespread destruction of status and the pathways to upward mobility.

Amazon Flex drivers, Uber workers, and InstaCart deliverers all have one thing in common: there is no obvious path to receiving a promotion or raising one’s status in the organization. A cab driver could save up to purchase his or her own medallion. A warehouse worker could rise to foreman. A delivery driver for a restaurant could become a waiter or a manager. There was the possibility that good work would be rewarded with rising pay and status. With the gig app regime, and much of Amazon’s warehouse apparatus, many of those avenues are closed off. Your rating may improve, but your rate of pay won’t. It’s worth noting that Chris Smalls, the leader of the first Amazon warehouse worker union, applied for a promotion dozens of times over the five years he worked at Amazon and was rejected every time, despite a productive work record.

The imposition of the factory system disrupted the paths that allowed weavers and croppers to rise from journeymen to masters, and that disruption was a major reason that their distress became so acute. Today, the alienating and isolating mode of gig work threatens on one hand to batter the livelihood of skilled workers, and, on the other hand, to lock workers into roles designated by proprietary algorithms, with no upward mobility on the horizon. A sense of hope, that one can better their lot through hard work and a mastery of their field, is a crucial and animating force in any healthy economy—and these gig‐based systems work to snuff it out.

When technological development is top-down and antidemocratic—and workers get no say in how automation or algorithms impact their daily lives.

The biggest reason that the last two hundred years have seen a series of conflicts between the employers who deploy technology and workers forced to navigate that technology is that we are still subject to what is, ultimately, a profoundly undemocratic means of developing, introducing, and integrating technology into society. Individual entrepreneurs and large corporations and next‐wave Frankensteins are allowed, even encouraged, to dictate the terms of that deployment, with the profit motive as their guide. Venture capital may be the radical apotheosis of this mode of technological development, capable as it is of funneling enormous sums of money into tech companies that can decide how they would like to build and unleash the products and services that shape society.

Take the rise of generative AI. Ambitious start‐ups like Midjourney, and well‐positioned Silicon Valley companies like OpenAI, are already offering on‐demand AI image and prose generation. Dall‐E spurred a backlash when it was unveiled in 2022, especially among artists and illustrators, who worry that such generators will take away work and degrade wages. If history is any guide, they’re almost certainly right. Dall‐E certainly isn’t as high in quality as a skilled human artist, and likely won’t be for some time, if ever—but as with the skilled cloth workers of the 1800s, that ultimately doesn’t matter. Dall‐E is cheaper and can pump out knockoff images in a heartbeat; companies will deem them good enough, and will turn to the program to save costs. Artists who rely on editorial and corporate commissions will see rates decline, all because the companies unleashed a disruptive technology without soliciting input from existing workers.

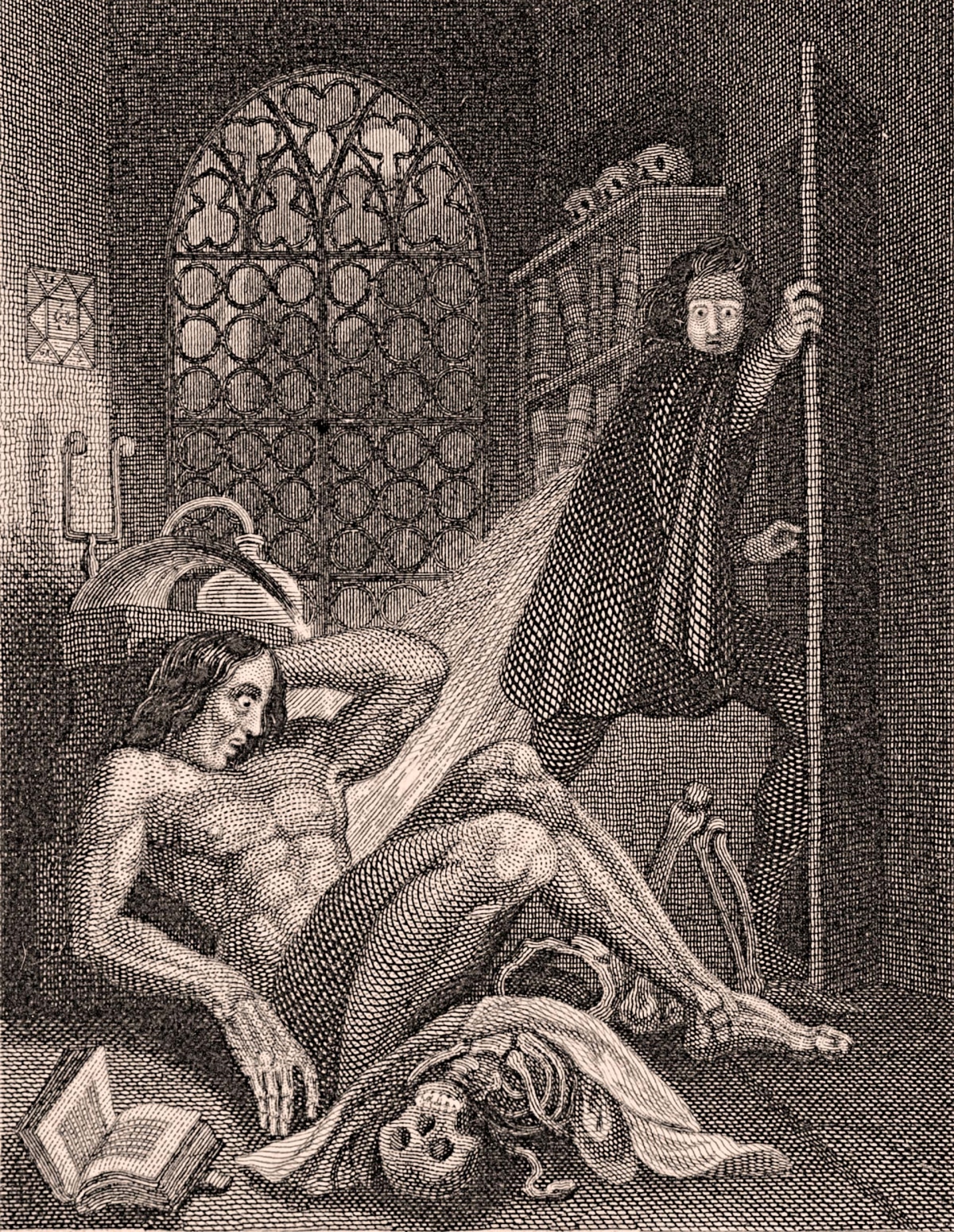

If ordinary humans and working people are not involved in determining how these technologies reshape our lives, and especially if those outcomes wind up degrading their livelihoods, time and again the anger will be acute and far‐reaching. And if workers cannot even legally organize with one another to cushion the blow, there is liable to be nowhere to turn at all, no option but to dismantle that technology. The same rage fueled (and may have helped inspire) a fictional contemporary of the Luddites too. When Mary Shelley dreamed up Dr. Frankenstein’s monster in 1816, she imagined him not as a simp, the way he would be portrayed in the movies, but as a thoughtful and articulate creature who ends up chafing, violently, against his impoverished, man-made existence.

The Luddite rebellion came at a time when the working class was beset by a confluence of crises that today seem all too familiar: economic depression and stagnant trade, rising inflation and high prices, excessive taxes for an unpopular war, and a government that strands unions, rules out serious relief for the poor, and declines to uphold industry regulations. And amid it all, entrepreneurs and industrialists pushing for new, dubiously legal, highly automated and labor‐saving modes of production.

With our jobs at risk, we are at risk. Our health, our security, our ability to plan for future generations—it all depends on access to decent work with decent benefits. Our capacity to lead a fulfilling and stable life is subject to the whims of the entrepreneurial elite.

The twenty‐first century has been filled with a lot of talk about how we have already entered a new machine age, a fresh system‐wide updating of the conditions that drove the Industrial Revolution. Whether our age is consumed by automation or not, whether the degradation of work at the hands of algorithmic regimes of work is total or not, it is an age marked by the erosion of traditions, identities, and good jobs, and the simultaneous increase of domination by the entrepreneurs, factory owners, and their allies. It is an age dominated utterly by Big Tech.

The time is again ripe for targeting the “machinery hurtful to commonality”—the gig app platforms, the fulfillment‐center surveillance, the delivery robots, the AI services, the list goes on—duly singled out by those whose livelihoods are being migrated, against their will, onto unforgiving technologized platforms, or degraded and whittled away by automated systems.

After all, for centuries ordinary people have had their autonomy pried away by new and elaborately exploitative technologies. More of our time, our work, our blood has been needed to run the machinery of profit, with less given to us in return. Nineteenth‐century artisans may not have had much, but they ran their own shops, plying their own trades, alongside their families, on their own terms. They had real freedom, the means to negotiate their wages, schedules, and their future. That, ultimately, is what the Luddites fought for.

Those Luddites rose up when their disparate grievances reached a fever pitch, uniting them in a struggle against the agents of their technologized exploitation. It may be only a matter of time before the rebel workers of the new machine age see the injustices of the on‐demand platforms as too much to bear, the surveillance apparatus of Big Tech too intrusive, the robotic pace of work too ruthlessly body‐breaking.

And if they feel the rage of Frankenstein’s monster, rebooted in a new era of boundless entrepreneurial adventuring, and they catch sight of those autonomous vehicles assembling like ghosts on the horizon, they might just reach, once again, for their hammers.

Adapted from Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech by Brian Merchant. Published by Little Brown and Company. Copyright © 2023 by Brian Merchant. All rights reserved.