- | 8:00 am

AI is going to transform Hollywood—but it won’t be a horror story

Generative AI is already changing the way film and television is made. And it’s for the better.

An odd new episode of South Park began floating around Twitter last summer. The characters and setting looked familiar, and the voices were almost right, but something was slightly off. In the episode, Eric Cartman is disappointed that Hollywood actors have gone on strike. He creates a deepfake app that can put any actor’s likeness into any movie and, with a friend, pitches it to Marc Andreessen. They also attempt to recruit Harrison Ford, Meryl Streep, and Tom Cruise, only to discover the actors are heading to Mars with Elon Musk.

The mini-episode was not made by the South Park creators but by a company called Fable Simulation, which lifted assets from the long-running animated series to showcase its new generative AI tool. Called Showrunner AI, it can write, direct, edit, and voice episodes of a show with just a little prompting. Unsurprisingly, there was a mixed reaction to the demo, which came out just a few weeks after the Screen Actors Guild and the Writers Guild of America (WGA) went on strike, partly over how AI might be used in Hollywood.

The fake episode isn’t “funny,” exactly—nor is it worth watching by anyone uninterested in Fable’s tech. Even so, it represents the deepest fears that Hollywood creatives and the general public have about AI: that in the near future, we’ll all be watching synthetic entertainment generated as cheaply as possible by the studios and networks, written by robots and acted out by computer-generated versions of beloved stars, a hollow and ersatz version of the films we loved.

But Fable sees things differently. It hopes that its brand of customizable content will offer viewers a new way to engage with TV shows. The company, which has raised money from Founders Fund and 8VC, is planning to launch an AI-generated animated series this winter that’s a satire of life in Silicon Valley. Fable will create the first season using AI. It’ll then hand the show over to a select group of creators, who will use its Showrunner tool to develop a season 2, with the original episodes serving as the training data. Eventually, episode generation will be open to viewers, who’ll be able to use Fable’s AI to design their own storylines.

Fable’s founder, Edward Saatchi, sees a future where there’s some sort of “Netflix of AI” that allows viewers to pick from an array of customized episodes of their favorite shows. “You [could] also speak to the television to say, ‘I’d like to have a new episode of the show, and maybe put me in it and have this happen in the episode,’” says Saatchi, who founded Oculus’s now defunct VR content studio before launching Fable in 2018. “In the next three to five years, that feels very achievable by the whole industry, so that the relationship between audience member and creator starts to fall away.” That’s the vision, at least.

Early adopters have a way of hyping how new technologies are going to radically transform our world. Typically, though, this world-changing tech often fades into something intriguing but very different from those promises. NFTs haven’t replaced the works in the Louvre, but that form of blockchain authentication can be useful for providing provenance for digital collectibles. We’re not all wearing Oculuses strapped to our heads and spending our days in the metaverse, either, but there’s a potential future in wearable glasses (we’ll see what happens when Apple’s comes out). The promise (or threat) of generative AI to completely upend how we consume entertainment seems similarly overblown.

“Almost everybody who talks about what is going to happen in this space puts almost no thought into how people actually consume media and what they want,” says writer-comedian Adam Conover, host of the Netflix series The G Word and a member of the board of directors for WGA West. Though the WGA negotiated protections from AI for writers in their new contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, Conover isn’t terribly worried. “Maybe there [will be] some AI-generated chum that shows up on Twitch and people have it on in the background while they do their homework,” he says. “But that’s not going to compete with movies. Movies are: ‘I want to go sit in the dark. I want to watch the hottest person in the world say the funniest things in the world and ride a real fucking motorcycle off a cliff.’ That’s what people want.”

Indeed, as Hollywood begins flirting with the possibilities of generative AI, the most encouraging developments so far seem less likely to replace humans than to assist them.

Thank You for Not Answering, by filmmaker Paul Trillo, is a dreamy experimental short about longing and loneliness—as interpreted by AI. Trillo handed the creation of the visuals for his film to the Gen-2 tool from AI research company Runway, which generated surreal snippets of a man and a woman. The accompanying voice-over, a message from a man to a long-lost love, was made with voice AI from ElevenLabs.

There’s nothing about the film, which debuted this past spring, that Trillo is trying to pass off as “real.” The features of humans are wonky and weird, almost haunted. At one point, a woman turns her head but her shoulders twist the other way, suggesting that the object of the man’s affection may have been related to Linda Blair in The Exorcist

THANK YOU FOR NOT ANSWERING from Paul Trillo on Vimeo.

Trillo often works with AI tools to create mind-bending visual effects. He recently directed a music video for French electronic producer Jacques that has the musician walking through the Louvre as trippy hallucinations of the art come to life, thanks to tools from Runway and Stable Diffusion. “I’m less interested in [using AI to make] things I can shoot with a camera than creating imagery I couldn’t create before,” Trillo explains.

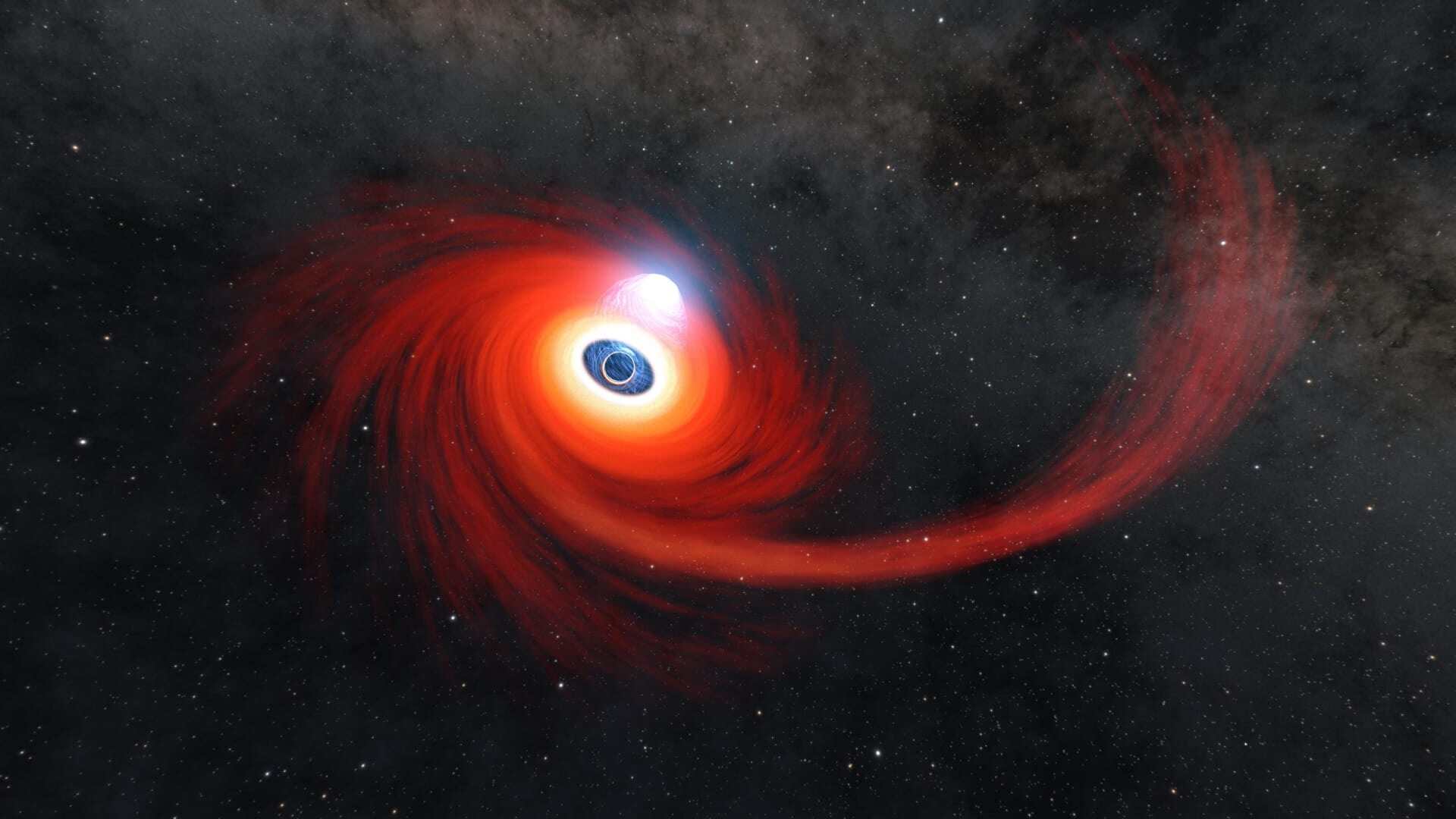

While the art-house world experiments with AI’s hallucinatory potential, visual-effects teams are using it to expand storytelling possibilities. A lot of traditional VFX involves really mundane tasks, editing something pixel by pixel, frame by frame—time-consuming and expensive work, says Lon Molnar, chief creative officer of the VFX company Monsters Aliens Robots Zombies (MARZ). Founded in 2018, the Toronto-based company has pioneered the use of Hollywood-grade generative AI to achieve better visual effects in less time and at less cost to studios. It brought the disembodied hand, Thing, to life in Netflix’s Wednesday, turned Paul Bettany into the android Vision for Marvel’s WandaVision, and de-aged a villain played by Willem Dafoe for the Marvel–Sony movie Spider-Man: No Way Home.

Though Molnar’s tech saves studios money, he doesn’t foresee blockbusters slashing their budgets as a result. “What happens [is] the audience demands more, right? More VFX, more spectacle,” he says. “When Game of Thrones came out, you got flying dragons burning down villages filled with people. We didn’t have that on TV before. Now that we’ve [seen] that, everybody expects to have it.” So instead of having dragons or White Walkers in just a few episodes, you could have them in every episode. Instead of just two dragons, you could have 10, or 100.

AI may make blockbusters more spectacular, but things will get even more interesting as smaller shows and indie filmmakers get ahold of these tools. MARZ already worked with the Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement–produced vampire comedy What We Do in the Shadows to create an enormous, Staten Island–dwelling troll for one of its episodes. Such well-rendered creatures are usually found in high-budget fantasy films, not campy FX comedies. But in another five to 10 years, Molnar says, smaller-budget movies and shows will have easy access to Marvel-quality effects. With de-aging tech, screenwriters can craft more ambitious time-skipping narratives. With the ability to render convincing cityscapes, historical dramas can roam far beyond the handful of carefully scouted locations that usually serve as their sets.

On the most basic level, generative AI can make low-budget films tremendously more polished. Trillo notes the high cost of going back to reshoot a scene to capture a line of dialogue, fix a continuity error, or insert an element that, in retrospect, is essential to the plot. None of this can be done on a tight budget. But with AI, you could “generate a video model [based] on all the footage from your scene, and then generate new shots based on the photography that you captured,” he says. “That’s going to rewrite the rules of postproduction.”

There are benefits for the distribution of film, too. MARZ’s latest AI tool, LipDub.AI, improves foreign language overdubs by manipulating the actor’s mouth, eliminating that often off-putting mismatch between lips and language. Foreign-language overdubbing is rare in North America, where we’re used to the small amount of foreign content we consume to be subtitled. But around the globe, dubbing remains extremely common, and audiences are used to watching American-made sitcoms and movies in local languages.

LipDub AI_Alternating languages_Squid Game from MARZ VFX on Vimeo.

The benefits for a big-budget film are clear, says Jonathan Bronfman, CEO of MARZ. If you can make Robert Downey Jr.’s Avengers Iron Man look like a fluent Mandarin speaker, “that movie is going to generate more revenue in China because the viewing experience is better,” he says. But this tech, which is being developed by several different companies, could also open the door for movies and TV shows from other countries to more easily break into the English-speaking market. Netflix has seen huge success recently with foreign-language series like the French thriller Lupin and South Korea’s Squid Game, with many Americans opting to watch the dubbed version. With better dubbing, even more Americans may choose this option—allowing emerging filmmakers across the globe to find larger audiences abroad.

Trippier images, improved special effects, lower postproduction costs, wider global distribution—this doesn’t exactly seem like the stuff of writers’ and actors’ worst nightmares. Even Trillo, who’s as far in on generative AI technology as anyone in Hollywood, still believes that the best filmmaking will come from something innately human: personal experience. “That’s what makes for interesting stories,” he says. “It’s the stuff that’s not in the training data.”