- | 9:00 am

The best Steve Jobs books might be yet to come

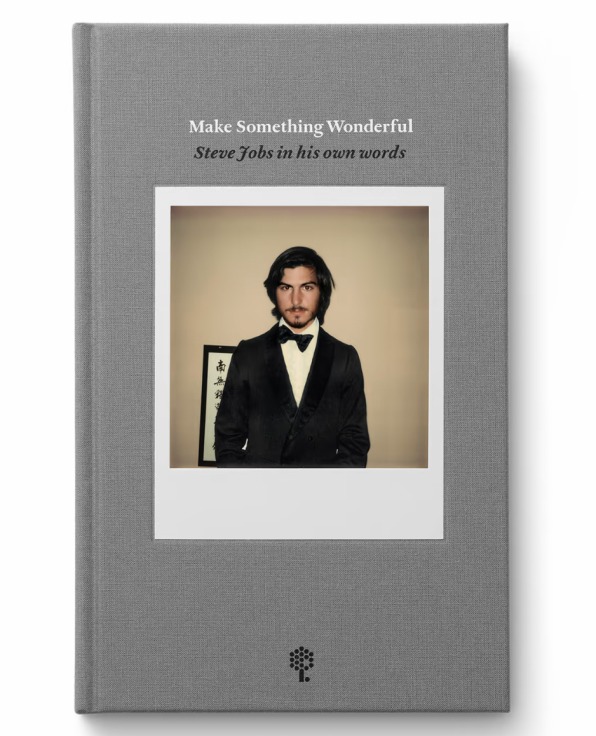

‘Make Something Wonderful’ lets Apple’s cofounder tell his own story. It’s welcome—but also a reminder of how elusive a subject he can be.

“The best way to understand a person is to listen to that person directly,” writes Laurene Powell Jobs in her introduction to Make Something Wonderful: Steve Jobs in His Own Words. A project of the Steve Jobs Archive, the website and free e-book—and limited-edition printed book—makes the case for that contention by curating her late husband’s thoughts about life, technology, business, and the intersection thereof. It was edited by Leslie Berlin, a distinguished historian of Silicon Valley and the executive director of the archive.

Human beings, in case you didn’t know, are complicated. Apple’s cofounder was more complicated than most, a fact that has dogged attempts to capture his legacy. For instance, the fact that some of Jobs’s closest friends and colleagues thought that Walter Isaacson’s Steve Jobs, the authorized biography, was too harsh redounded to the benefit of Becoming Steve Jobs, an unofficial but uncommonly well-sourced book by Brent Schlender and my former Fast Company colleague Rick Tetzeli. Inevitably, some people then said that book wasn’t harsh enough.

As for Make Something Wonderful, Six Colors’ Jason Snell says he worries that it’s a “hagiographic tool” designed to shape history’s assessment of Jobs. With any luck, history will remember that a publication assembled by Jobs’s family and friends was never going to present an unvarnished portrait of the man. But with that proviso in mind, the creators of Make Something Wonderful have indeed made something wonderful.

It’s worth your time for the resonant photos alone, many of which I don’t recall seeing before, such as one of Jobs staring pensively at a NeXT computer mockup fashioned from Styrofoam. There are also some well-chosen excerpts from Jobs’s interviews, along with sound bites from his public appearances—a few of which I witnessed in person as a member of the press.

But to me, the most fascinating contents are Jobs’s hitherto-unseen emails to colleagues, tech-industry notables, such as Intel’s Andy Grove, and—since he used his inbox as a convenient means of note-taking—himself. He’s direct, thoughtful, and sometimes unexpectedly humble. In one instance, as he’s trying to get skeptical Pixar employees excited about the company’s upcoming holiday waltz, he’s even charmingly goofy. (“As for being single, all I can say is that cutting in on a lovely lady or elegant gentleman during a waltz is considered proper and flattering.”)

Still, Steve Jobs can only tell us so much about Steve Jobs. His resistance to looking backward was a defining asset when it came to running Apple, but also means that his accounts of his own history can be shallow. Explaining critical moments, such as his ouster from Apple in 1985, requires weaving together multiple viewpoints with context and objectivity. And even then, it isn’t easy. There are certainly some fine books about Jobs and his company—starting with the first one, Michael Moritz’s The Little Kingdom, published in 1984 and still in print in a revised edition—but none feels like the last such book anyone will ever need to write.

Though the Steve Jobs Archive hasn’t said a whole lot about its goals and holdings, it would be a shame if any still-unseen materials it possesses were guarded too zealously. They could be essential reading for future historians, especially as the opportunity to conduct new interviews with people who knew Jobs fades away. (Sadly, former Apple PR chief Katie Cotton, a key confidant, passed away earlier this month.)

In a world that’s still giving us new books about Julius Caesar, it’s a safe bet that people will still be writing and reading books about Jobs and Apple decades from now. With any luck, their distance will add perspective—and help us make sense of a remarkable story we’re still only beginning to understand.