- | 8:00 am

The future of the museum is an empty room that can take you anywhere

The Invisible Worlds exhibition at New York’s museum of natural history gives new meaning to the immersive experience.

How do you display nature? At New York’s 154-year-old American Museum of Natural History, there are exhibits of eye-popping specimens and artifacts: gems and minerals, dinosaurs and early human ancestors, the most detailed 3D atlas of the observable universe. And of course, there are the dioramas, the highly realistic replicas of landscapes, complete with taxidermy animals and replicas of long-dead humans. As the years have changed, the exhibits have stayed remarkably consistent. “The best thing [about] the museum was that everything stayed right where it was,” raved Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye. “The only thing that would be different would be you.”

But that’s all history now. The museum’s newest answer to the question is a space that is, in fact, all about change, and, because everything is connected, even changes with you. Its newly opened wing, the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, was designed by Jeanne Gang and her Studio Gang, with interlocking corridors linking to the rest of the sprawling campus. Its wind-swept facade and undulating, canyonlike atrium do away with hierarchies and strictures, and instead cultivate a feeling of interconnectedness. The feeling pervades the new exhibits: a butterfly room, an insectarium—including a sprawling ant farm, where half a million leaf-cutters are farming fungus—a four-story glass wall uncovering highlights from the museum’s gargantuan archive, and, at its dark center, a snaking collection of tiny natural wonders that ends in a cavernous room called “Invisible Worlds.”

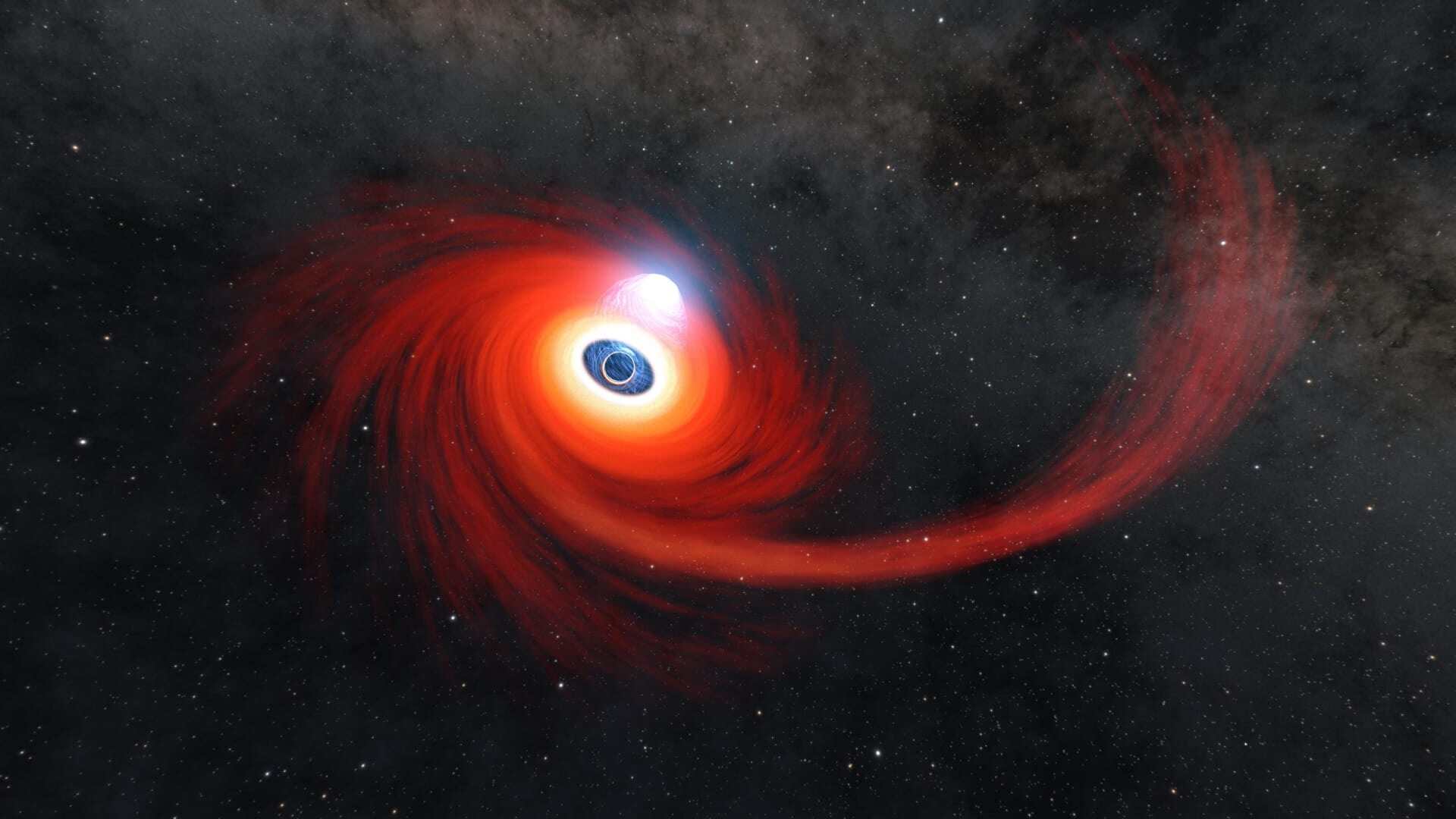

Imagine an immersive Planet Earth, or Powers of Ten, built with powerful GPUs, 3D software, and a constellation of speakers and laser projectors that respond to you. Move into the dark rink-size space and you see a fungal network branching across the walls and floor. As you get your bearings, your sense of perspective and scale, you step on one route and water glides along it. Then you’re floating up to the rainforest canopy, with lemurs and snakes and a giant hummingbird and a leaf in its microscopic glory, and flocks of birds that fly around you on their way north. Next, flying from space down to Manhattan, you see humans’ own digital signals, not unlike those fungal networks, or elsewhere, the webs of neurons that also signal when you step on them. Later, deep in San Diego Bay, a giant humpback, blue in a veil of glowing plankton, emerges from the darkness with a low wail, dwarfing you and everyone else.

“What we wanted, hopefully, to get across is that we are active in nature,” says Marc Tamschick, the Berliner whose studio, Tamschick Media+Space, led the team of designers behind Invisible Worlds. “We are active agents, we’re not passive viewers.”

To build it, his team consulted dozens of museum curators and scientists and gathered torrents of real-world data. And yet, in a feat of modern science communication, the show manages to avoid hitting you over the head with either the tech or the science.

“If you dig deeper, you’ll find relationships to all the galleries in the museum. And I think people will add their own memories to what they see,” he says, “and then it kind of starts to open the heart.”

When I first visited the room in January to see an early version, I understood what he meant. Just a week before, I had been in the Gulf of California, following humpbacks at the start of their breeding season. It’s hard to describe the vertiginous feeling of glimpsing these majestic animals even at a distance; now I was underwater with one of them, and I wanted to stay there.

“I was afraid when we were developing this that it would be completely overwhelming,” says Vivian Trakinski, director of science visualization at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). “But when we came in for the first time, it was peaceful, it was contemplative.”

You can see the room as a reflection of how the museum itself has been contemplating its own place in the universe. The theater, like the rest of the new wing, is clearly part of a bigger response to challenges facing many museums: how to stay modern, open up their collections, and win over new audiences amid growing competition for attention. And that ties into bigger questions about how nature and science are represented—and by whom, and for whom. For the museum’s leaders, Trakinski says that’s meant grappling with “issues around DEI, and colonization, and how we think about our cultural halls—and what is the role of natural history museums?”

Trakinski, who’s overseen more than 50 short documentaries and science shows, and started her career at “3-2-1 CONTACT,” can’t help but zoom out to bigger questions, too. “How does the museum help bring people together, and help heal the divide of the country and not be on this side of the debate because we’re ‘science’?” And that’s an enormously difficult position for a science institution to take. Because there is a true and a not true, a right and wrong.”

“But,” she adds, “I think that’s where the art comes in.”

THE IMMERSIVE RUSH

Art in this context isn’t just about interpreting the invisible parts of nature, but also about one not-so-invisible trend emanating from the art world. The immersive experience isn’t new: we’ve had dioramas and haunted houses and phantasmagoria for centuries. Yayoi Kusama has been creating immersive rooms since the ‘60s, which is also when multi-projector theaters first popped up, beginning with Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen’s IBM pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. But the modern version, born in the mid-2000s, took off in the past decade on the back of a blockbuster Van Gogh show. By the late pandemic, the Dutch master’s work was the subject of a dozen competing shows around the globe, sprawling spaces where you could pay a premium to get psychedelic with the canonical dorm room “Starry Night” poster (no acid required), before a stop at an equally sprawling gift shop.

The shows have since popped up like so many sunflowers (or brand activations), recycling the works of Monet, Kahlo, Dali, and Picasso, or the imagery of NASA, or the IP of TV sitcoms into kitsch. Disney and Universal and dozens of companies see a piece of the experience economy that some estimate at $61 billion; struggling museums see new opportunities. As actual experiences, they may be informative or mesmerizing or, in their more thoughtful forms, transporting. The ones I’ve seen were more like giant screensavers, which look great in photos. Everything moves . . . but they weren’t moving.

I mention the trend to Tamschick, and he purses his lips. “Some of them are more impressive than others,” he says. “But usually you go in, and you have a half-hour show, and after 10 minutes you are bored. It’s super Instagrammable—but you don’t have real content.”

For Tamschick, who’s been projecting animations since the mid-1990s, so much immersion depends on context, on story, and on the space itself. (For the architecture of the exhibition, his team worked with Seville-based Boris Micka Associates.) Interactivity adds another immersive element. It’s all part of what he calls the scenography. “It’s a French word the Germans use to describe interior architecture in the museum,” and the search for “a new way to narrate the parkour of your visit,” he says. Tamschick’s studio has designed exhibitions for museums around the world, but each project merits its own approach, especially now. “I think the new rule is, there’s no rule.”

To build a compelling show about things that, by definition, can be hard to visualize—a show focused on what he calls “truly science visualization and its results”—his team would still need to grapple with a key question.

“Our battle was, how much can we invent?” Could they move the position of the sun or the shadows or certain objects? Could they use abstract paint strokes to represent things that are hard to represent? You can use software to visualize nature based on data, of course, and with increasing accuracy, but “you could do so many other things too.”

HOW THEY BUILT AN IMMERSIVE DIORAMA

The question of realism, about depicting nature as it actually exists, dates back well over a century, to the museum’s first immersive exhibits. Carl Akeley, the founder of the AMNH’s Exhibitions Lab, believed that the museum diorama was more than entertainment, that it could help educate the public about the growing need for conservation. That meant producing scientifically accurate replicas in ways that not only looked lifelike, but alive, and in ways that would elevate taxidermy and dioramas from crude crafts to a kind of art.

For nearly two decades, Akeley led a team of artists and scientists building dioramas based on specimens they collected during elaborate African expeditions. But his attitudes on exotic taxidermy, sometimes gathered from game hunters, changed after “collecting” several mountain gorillas. It was Akeley who influenced King Albert I of Belgium to establish Africa’s first national park in 1925. Known today as Virunga National Park, it’s home to a quarter of the world’s mountain gorillas. Akeley died a year later, during his fifth visit to the Congo; and a decade later, his lab opened the Akeley Hall of African Mammals, a taxidermy tour de force featuring a menagerie of specimens as they appear in re-creations of their habitats. The mountain gorillas are depicted on Mount Mikeno, where Akeley died.

But the museum is still grappling with the legacies of Akeley and his era. By the racist, colonialist logic of the early conservation movement, white Europeans weren’t part of “nature,” but separate, responsible for taming and collecting it. The logic extended to Indigenous societies, too: Even today, many conservation programs in Africa prioritize the nature they seek to protect over the local people who live there. In the new Northwest Coast Hall, which opened last summer, there are no life-size dioramas. Instead, cultural objects are on display with commentary from curators from Indigenous societies—Coast Salish, Gitxsan, Haida, Haíltzaqv, Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Nuxalk, Tlingit, and Tsimshian.

Akeley’s other legacies still linger, even over the new wing. The sandpapery spray-on concrete, or shotcrete, that Studio Gang used for the interior of the Gilder Center’s undulating atrium was patented by Akeley, and the lab he started is still in charge of all immersive environments at the museum, including Invisible Worlds.

To begin building the modern incarnation of the diorama, Tamschick and his team would need to go on their own specimen-gathering expedition. As they started to sketch out concepts for the story and visuals, they spent months meeting one-on-one with dozens of the museum’s 200 researchers. “They would tell us their most interesting discovery, or the coolest new thing in their field,” he says. The researchers would later give feedback on the story and visuals, too. “It was not, ‘Come back with a new proposal, redo this,’ but it was always iterative, and growing.” He grins. “And I got to touch dinosaur bones!”

As the designers built storyboards, illustrations, and renderings, researchers fed them digital artifacts and real-world data. The final 12-minute loop includes visualizations of LiDAR scans of New York City, 3D renderings of a dragonfly’s nervous system, airplane-traffic data, models of fish schooling behavior, and a map of the human brain. There’s video composites of plankton from footage shot in San Diego Bay, animals from a 15-story canopy in Brazil’s Caxiuanã National Forest, and real scenes of Central Park. Scientists would review everything, acknowledging that depicting nature always involves taking some liberties. “You stay true to the data, but the process of visualization is interpretation,” says Trakinski.

Still, she says, modern software allows for replicas of nature that aren’t just interpretations or animations, but elaborate visualizations of actual data. During a recent experiment with Microsoft’s HoloLens, Trakinski examined a digital representation of an actual mako shark skeleton, made using CT scans. The museum’s scientists, she was surprised to learn, “didn’t call them digital artifacts, but digital specimens,” she says, “because they are as first order to investigation as the physical object.”

Beyond the HoloLens, the museum has experimented with other immersive setups, including VR helmets, to more easily open up its towering collection of digital specimens. But the technology is still too distracting, says Trakinski, and discourages interaction with others. Tamschick sighs in agreement. “In 5 years, we will have glasses which allow certain things, and maybe in 10 years it’s, again, something completely different,” he says.

With or without computer goggles, Trakinski says, immersive experiences are most powerful when they can be collaborative. She recalls a hackathon the museum’s Hayden Planetarium hosted with astronomers centered around OpenSpace, an open-source data visualization program it built with help from NASA. As they projected their data onto the dome, the researchers began finding patterns, asking questions, tweaking parameters. “They started to do real science,” she says. “And to me, that’s the coolest thing.”

The team behind Invisible Worlds imagined similar possibilities for mutual discovery, even among strangers.

“When you walk through the streets, everyone does his own thing,” Tamschick says. “But I believe that in the moment where you start to interact with something that is new to you, suddenly the space will become playful, and suddenly you can imagine that two people are standing close to each other and discover this together, perhaps touch each other.”

Making the audience part of the exhibition itself isn’t just a function of imagery and interaction. The team also worked with sound designer Peter Hylenski and composer David Kamp to build a moving, 3D soundtrack for an array of 62 Dmitri speakers. The idea, says Tamschick, was to conjure up “a natural habitat [that can] trigger other things from your experiences.”

“Of course, you haven’t been inside a human brain, you may not have heard the rhythm of blood pressure, or hear when a butterfly moves its wings, but you have the whoomp whoomp—and it sounds like techno.”

For the visuals, the team initially considered using curtains of LEDs. That would mean a brighter picture without excess light, but projectors were cheaper, and easier to use and repair; plus, in tests, the designers liked the way the light splashed on visitors, which “makes it more of an immersive and attractive experience,” says Tamschick. Because they began by designing for a space that didn’t exist, much of the testing took place using a mock-up in Berlin, and a more accurate digital twin of the room rendered in virtual reality. Still, when he first visited the nearly-finished bowl last summer, with its 23 foot walls, “I was terrified that they were going to light up the projectors and I was gonna barf.”

He didn’t. The system they settled on features 16 Christie laser projectors, which cover the walls in lush light, with real world colors, the blackest blacks, and a resolution of more than 100 million pixels. Each machine requires four people to lift and sits in a ring above the bowl in a brightly lit projector room that’s perpetually humming with fans. (The planetarium uses similar machines for its stunning fulldome projections.) Next door, an even more secure room houses racks of GPU-laden servers. As one set of projectors displays the linear story, another manages the real-time interactive elements—the plankton and neurons that move and glow—based on input from an array of infrared sensors. If any part fails, the system can be quickly switched to a fallback arrangement.

“The machine up there is so impressive,” says Tamschick, standing in the bowl weeks before opening day, as the team was busy fine-tuning imagery, fixing pixels, correcting colors. One of his favorite things is how invisible the thing is. “I don’t want people to see the technology,” he says.

The system can display other content too, like a cinema in the round or “an immersive PowerPoint,” says Benjy Bernhardt, who directs the museum’s Electronic Media Engineering and Support department. Some programmers and researchers are already eager to use it after hours, he says. “The kind of presentations people have generally done in the planetarium or on flat screens, we’re planning to be able to do that here with speed and finesse, and better than previous installations.”

After the painstaking production, Tamschick’s ears prick up at the thought.

“I think the potential would be, first of all, to be able to produce shows for this kind of format in a way that’s less involved, with less time and money, so you can be quicker,” he says. (The wing cost the museum $465 million, but it hasn’t said what it spent on Invisible Worlds.) The experience has also left Tamschick eager to push science visualization into more abstract territory, and push audiences further too.

And amid the fevered rush toward immersive spectacle, he emphasizes the need to keep searching for deeper connections.

“I think there is a super future for these kinds of spaces, but it has to be done carefully,” he adds. “Otherwise, it’s a lot of bling bling, and what does it serve? What’s the purpose?”