- | 9:00 am

We need a better way to find AI’s dangerous flaws

To make AI systems safe, we need to pay people to experiment with them out in public.

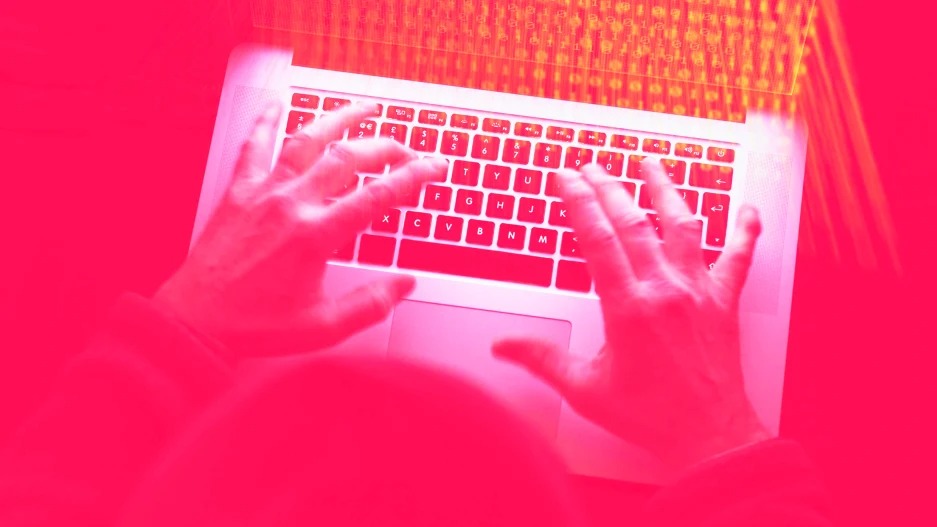

As concerns mount about AI’s risk to society, a human-first approach has emerged as an important way to keep AIs in check. That approach, called red-teaming, relies on teams of people to poke and prod these systems to make them misbehave in order to reveal vulnerabilities the developers can try to address. Red-teaming comes in lots of flavors, ranging from organically formed communities on social media to officially sanctioned government events to internal corporate efforts. Just recently, OpenAI announced a call to hire contract red-teamers the company can summon as needed.

These are all helpful initiatives for mitigating bias and security risks in generative AI systems, but each one falls short in a crucial way. We believe what’s needed is red-teaming guided by two principles: It should be public, and it should be paid.

When people get their hands on fancy new generative AI apps like ChatGPT and Midjourney, they want to see what they can, and cannot, do. Many users find it fun to share their experiences online by posting amusing, surprising, or disturbing generative AI interactions to social media. This has led to viral tweets and popular subreddits. Most of us who come across this content online find it entertaining and informative. We laugh at the AIs’ blunders and learn how to manage their wanton recalcitrance.

To the tech companies behind these AI products, these social media posts aren’t just fun; they’re free labor. When users post how to “jailbreak” an AI—sharing prompts that bypass the built-in guardrails—the AI’s developer can adjust the guardrails to make them resistant. When users post screenshots of an AI saying or depicting something dangerous or derogatory, the company sees what updates the AI needs in order to convince customers it is safe.

This is a tried-and-true strategy in the tech industry: Release flawed products into the wild and let the public do the hard—and un-remunerated—work of cleaning up the mess. That’s the social media playbook, and so far it’s looking like the AI playbook as well.

For a non-profit like Wikipedia, there’s nothing wrong with this approach. A community of dedicated volunteers believes in the vision behind the site and enthusiastically works to support it. But when we’re talking about a for-profit tech company, especially one whose products run the risk of destabilizing democracies and fanning the flames of hate, things are different. The people making corporate products safer should be economically incentivized to do this dirty work, and they should be financially rewarded for their labor.

The term red-teaming is borrowed from the world of cybersecurity testing, where “red” hackers vie against “blue” defenders to uncover security vulnerabilities in software. One of the first instances was in the Cold War, where the red team represented Soviet hackers. Red-teaming AI is a more nascent practice, aimed at mitigating bias, security risks, and incitements to violence (a growing issue as cases of suicide and attempted regicide encouraged by chatbot have already surfaced).

OpenAI’s partner Microsoft recently outlined the company’s history of internal AI red-teaming efforts and offered best practices to help others in the industry follow suit. Microsoft’s team officially launched in 2018 but the company boasts of precedents reaching as far back as a “Trustworthy Computing” memo circulated more than 20 years ago. However, it’s difficult to find details such as how large Microsoft’s AI red team is or what fraction of the development budget is dedicated to this team.

One month before Microsoft’s post on AI red-teaming, Google published its first report on AI red-teaming, including a nice categorization of the risks they seek to address and the lessons learned so far. Meta mentions performing red-teaming exercises on particular AI systems like its open source language model (LLM) Llama 2, but the scope of these exercises are unclear (and past debacles such as the flopped release of Meta’s AI system Galactica suggest they haven’t always been sufficient).

These corporate AI red-teaming efforts and documents are important, but there are two big limitations to them.

First, when internal red teams uncover abhorrent AI behavior that could spook investors and scare off customers, the company could try to fix the problem—or they could just ignore it and hope not enough people notice, or care. There is no accountability imposed. Second, the landscape of possible inputs to AI systems is far too vast for any one team to explore. Just ask New York Times tech columnist Kevin Roose, who tested Microsoft’s Bing chatbot, powered by GPT-4, in ways the company’s internal red teams had missed: his prompts led the chatbot to beg him to leave his wife.

OpenAI’s recent call for applicants to join a broad, paid network of red-teamers helps address this second limitation, because it allows the company to expand red-teaming efforts far beyond what a small internal team of well-paid, full-time employees can accomplish. And it could address the first limitation as well, because these external testers could share their findings with the public. Except they can’t, because OpenAI is requiring everyone in this red team network to sign a nondisclosure agreement. That’s a tremendous shame, and yet another irony for a company with “open” in its name.

Before release, when developers are probing a system internally, there is a case to be made for secrecy. But once a product is let loose in society, we are all entitled to know what problems have been found within it. This is particularly true for generative AI products since the harms stemming from these are not limited to their users—we are all exposed to risks including bias, defamation, and the undermining of elections. You cannot opt out of these risks simply by not using these AI systems, so the companies behind them should not be allowed to opt out of revealing the problems red-teamers have uncovered.

Public-facing AI products need red-teaming before they are released but also throughout their consumer-facing lifetimes. It should be the financial responsibility of tech companies to continuously monitor the AI systems they provide; simply hoping it happens for free or waiting until organizations like the White House step in and do it for them is insufficient. This should include paid networks of external red teamers as well as “bug bounties,” which are cash prizes to anyone who uncovers dangerous AI behavior—and the bug bounties should cover all ranges of harms, not just security vulnerabilities.

A more comprehensive and professional approach to red-teaming could help ensure a diverse array of backgrounds and languages is included in the red-teaming efforts. This is particularly important for uncovering bias and harmful stereotypes embedded in AI systems. And crucially, all red-teaming performed after a product is released should be made public; NDAs of the type OpenAI is requiring should be forbidden.

That said, the tech industry is not a level playing field, and all too often regulation ends up solidifying the monopoly power of entrenched tech giants. We should find ways to shift the financial burden so that the cost of public red-teaming is borne more heavily by larger firms, to allow room for startups to enter the market. One possibility is a progressive tax on revenue from AI products that helps fund government-sponsored red-teaming activities. Progressive here doesn’t mean liberal politics—it means the tax rate goes up as the size of the firm increases. Having red-teaming results published openly also helps vitalize the market because it allows all firms to freely learn from the red-teaming that the incumbent firms pay for. This is a form of data sharing that benefits everyone.

AI systems are far less predictable than traditional computer systems that follow precise sets of instructions determined by the developers. We cannot simply look at the computer code behind AI systems to see how they will behave—we really need to experiment with them to see what they’ll do. While there is a history of using red-teaming to uncover security gaps in computers and other real-world systems, with AI the need for red-teaming is far wider—without it, companies are literally placing mysterious entities into the hands of hundreds of millions of users without knowing what they’ll say or do. And this is also true of older AI systems like the ones powering social media platforms, not just the shiny new generative AI apps.

There is much discussion of the risks surrounding AI; it’s time to focus on what we can do about them. Red-teaming is one of the best tools we have so far, but we should not allow it to be done behind closed doors. Nor should we rely on unpaid communities on Reddit and TikTok to provide this important labor. And we should not delude ourselves into thinking that all societal problems associated with AI can be addressed by red-teaming. Some things, such as the erosion of our information ecosystem and mass unemployment caused by automation, extend far beyond the scope of red teams. But paid, public red teams would be a strong step in the right direction.