- | 9:00 am

What happens when technology replaces the need for workers?

In their new book, professors Christopher Wong Michaelson and Jennifer Tosti-Kharas explore what the future of meaningful work looks like.

Visitors to Walt Disney World cannot help but be confronted with founder and visionary Walt Disney’s obsession with the future. Evidence is all over the park, from Tomorrowland in the Magic Kingdom to the geodesic dome presiding over the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, better known as Epcot. The It’s a Small World ride gets outsize attention and for good reason, with its dubiously diverse children swaying to an earworm tune as visitors meander through a psychedelically rendered global tableau (as in Epcot’s World Showcase, European countries are oversampled), ultimately arriving at a heavenly room where the children are all together and, inexplicably, dressed in white.

But it’s Tomorrowland’s Carousel of Progress attraction that perhaps best links Walt’s vision of the future to how the actual future has played out—and continues to play out today. A narrator informs the audience that the show they are about to see was originally created for the 1964 World’s Fair as part of the “Progressland Pavilion” and has staged more performances and been viewed by more people than any other show in American history.

The production, we are told, was Walt’s own creation, “from beginning to end,” featuring a stationary circular stage with a seating area for the audience that revolves around the stage— hence, carousel. The stage has four sections, each approximately two to three decades after the previous section, which together trace the whole of the 20th century. We open on a turn-of-the- century household where the father lists the merits of the new icebox, the mother has a new washing machine that enables her to “only” spend five hours doing the wash, the son entertains himself with a stereoscope, and the daughter prepares for a Valentine’s Day dance in town at which she will arrive via the new horseless trolley.

We follow this same family over the years until we arrive at the conveniences of today. Mom is programming the smart home devices on her computer, which Dad tests out by using voice commands to raise the oven’s temperature and lower the lights, Junior is playing a video game on a virtual reality headset with Grandma, and so on.

The themes of the Carousel of Progress are, as Disney themes tend to be, unsubtle. The characters remind us that each generation believes that things couldn’t possibly be any better than they are today. The song “There’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow,” which repeats with each revolution and rivals “It’s a Small World” in both its utopian optimism and its ability to haunt the listener’s every waking minute, reminds us that this beautiful tomorrow “is just a dream away.” In the present, we can’t imagine a better world, but thanks to a combination of human ingenuity and technological advancement that better world will come.

The carousel does manage to work in a few potentially dystopian angles. The 1940s-era dad decries his new automobile-enabled trip to work:

Oh, and here’s something else that’s new. I just heard a new term today on the radio. Fella says we’ve got something now called the “rat race.” Did you ever hear that one? Sure describes my life. I’m involved in something now called “commuting.” I drive into the city for work all day and then turn right around and drive all the way back. And the highway is crowded with fellow rats doing the same thing!

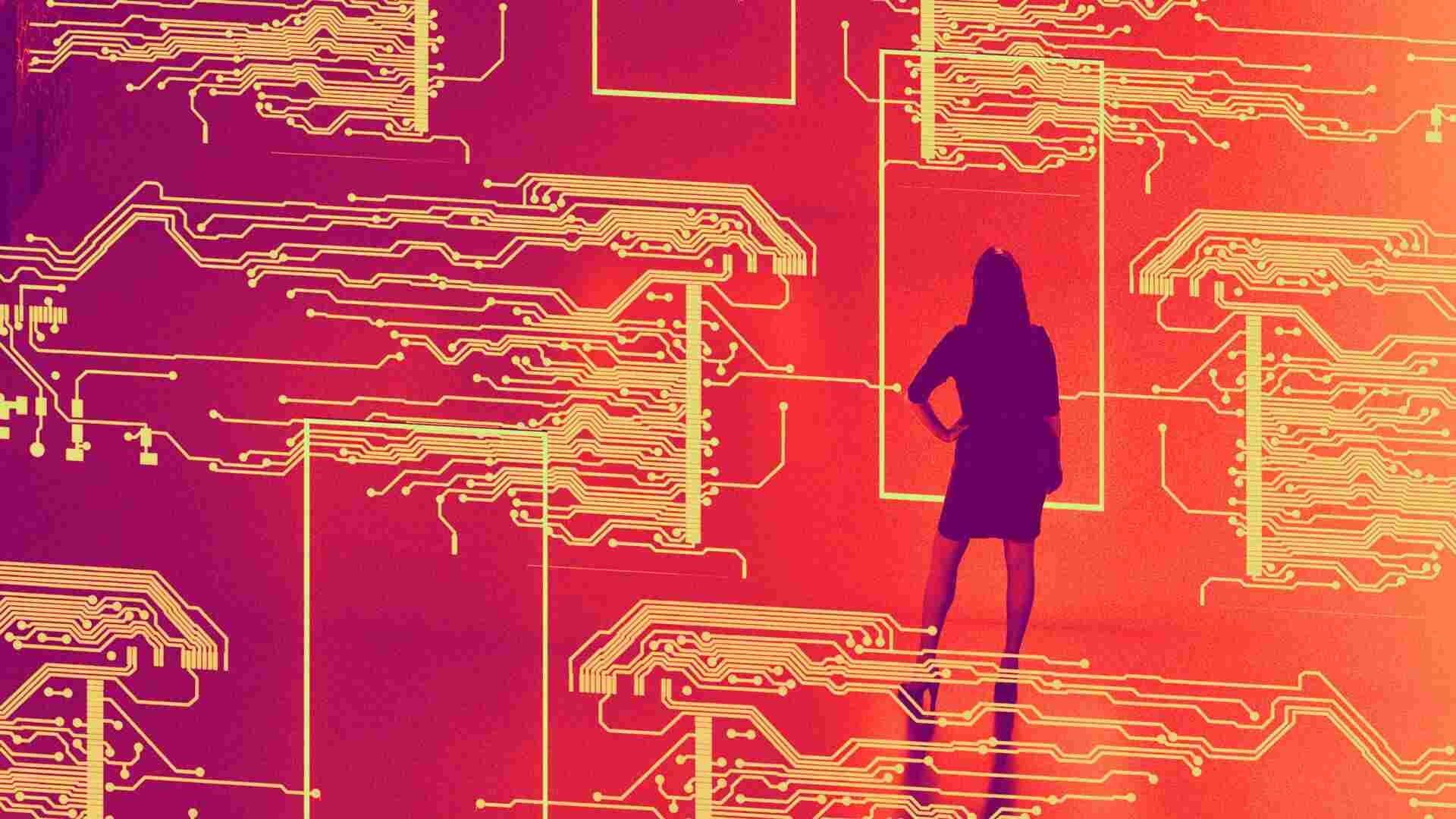

Meanwhile, present-day Dad manages to inadvertently turn the smart oven up so high that he burns the Christmas turkey, while Grandpa voices offstage complaints about the smart toilet. Still, the most foreboding element of the proceedings may be the simple fact of the 32 “audio-animatronic” robots who comprise the cast of Carousel of Tomorrow. In a posted version of the script dated 1994, the narrator proudly highlights that these actors are able to perform consistently all day long without needing a break. Sound familiar? Interestingly, in more recent performances, that part has been omitted. Whether or not this was a deliberate decision informed by its potential to strike fear in the hearts of Disney guests who acutely feel the threat of themselves being replaced by similar automatons, the implication is clear: The robots are coming for at least some of our jobs in the great big beautiful tomorrow.

Economists from Adam Smith to John Maynard Keynes have been predicting for centuries that machines would free us up for lives of leisure, a condition Keynes described as “technological unemployment,” and estimated that by 2030 people would need to work only 15 hours per week. More recently, World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab coined the term Fourth Industrial Revolution to portray a future in which machines might usurp manual labor, and artificial intelligence could render knowledge workers jobless, bringing about an existential crisis and survival angst.

Reports from the World Bank and McKinsey estimate that somewhere between 45% and 65% of jobs are at risk from automation, with the number highest for the lowest-paid jobs and those in developing countries. Speculation abounds on which jobs will eventually be outsourced completely, how any given job might be altered by advances in sentient AI, and whether this is good news or bad news for human lives worth living.

Yet, in today’s society, filling our time with work allows us the luxury of not having to decide what it is we truly want to do with our lives. A lifetime of leisure brought on by the end of work portends a different kind of pressure. This new state of affairs gives rise to the dystopian tension to live a meaningful life devoid of the kind of work that we may not previously have realized gives structure to our days and an implied worth to our existence. If our work gives our lives more meaning, what happens when it goes away? Can something fill this void? Whether forced upon us because our work has been taken away or because unemployment has been given to us as a gift, our ideals about how to live in a potential future without work can inform our thinking about our reality of how to live in our present world with work.

Excerpted with permission from Is Your Work Worth It? How to Think About Meaningful Work by Christopher Wong Michaelson and Jennifer Tosti-Kharas. Copyright © 2024. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group.