- | 8:00 am

A neuroscientist reveals the untapped solution to create better working relationships

In this Q&A, Dr. Perry illustrates how catalyzing certain conversations unlocks the collaboration we need to meet the moment.

Hope was the last emotion I expected to feel after doing interviews about trauma. Yet, my conversations with Dr. Bruce Perry about What Happened to You?, the book he coauthored with Oprah Winfrey, continually reinvigorate it. I strive to be optimistic. Still, global tragedies often leave me wondering how to heal a broken world. Fortunately, Dr. Perry, principal of the Neurosequential Network, has a solution, and it’s simpler than you might think: Be present in your relationships.

“If we moved from a state of relational poverty to relational wealth— meaning we had more relational interaction, and thus a more regulated population—we’d have access to millions more units of cognitive power. There would be a quantum leap in creativity and invention. It would revolutionize the planet.”

How do we build relational wealth? By becoming curious about the experiences that shaped the people in our communities and organizations. Here, he illustrates how catalyzing these conversations unlocks the collaboration we need to meet the moment.

Fast Company: What does it actually look like to invite and support someone to be their whole self?

Bruce Perry: It takes courage and intimacy to share your personal narrative. This process is interesting because as you share details about yourself, your brain’s relational monitoring apparatus is studying how they’re being perceived. As soon as you sense that someone is disengaged, you stop sharing that part of yourself. The things we listen and respond to joyfully tend to be what resonates with us. So, our impression of someone ends up being just as much a reflection of us as it is of them.

Imagine somebody’s life is a canvas. If you fill in every piece of that canvas, you have a high definition understanding of that person. But, if you don’t look at the upper right hand corner, those pixels never get filled in. It takes a very secure person to let someone’s full story unfold. When you can listen to topics that make you feel anxious or uninterested, you can come to know a person more completely.

FC: It’s important for people to decide when and how much of their story they share, particularly traumatic experiences. Paint a picture of the ideal scenario of being told a painful story. What tips might we keep in mind as the receiver?

BP: When you visit an emotional topic, it’s hard to stay with that intensity for a long time. You’re vulnerable and concerned about whether someone will protect your experience. Are they going to minimize it? Are they going to try to empathize with the loss of your child because their pet just died? You can imagine what that does to a parent’s sense of: How are you taking care of what I’m giving you?

You want to treat these emotional disclosures like a gift because they are. The best thing you can do is listen. One of our immediate responses is to cover up that gift with distractions or our own emotional exclamations. It’s hard to do, but don’t feel pressured to fill in the silences. They just want to tell you what colors to paint those pixels in the upper right hand corner.

The second thing is to say: I know this is really hard to talk about. I appreciate that you’re sharing it with me. You want them to know that you’re able to hear their story. Listening resists the tendency to try to fix it, because you can’t. Sitting with someone in their pain is a lifeline. It’s a silver thread of hope in a dark space.

FC: How can we use our understanding of what happened to each other to better connect and collaborate?

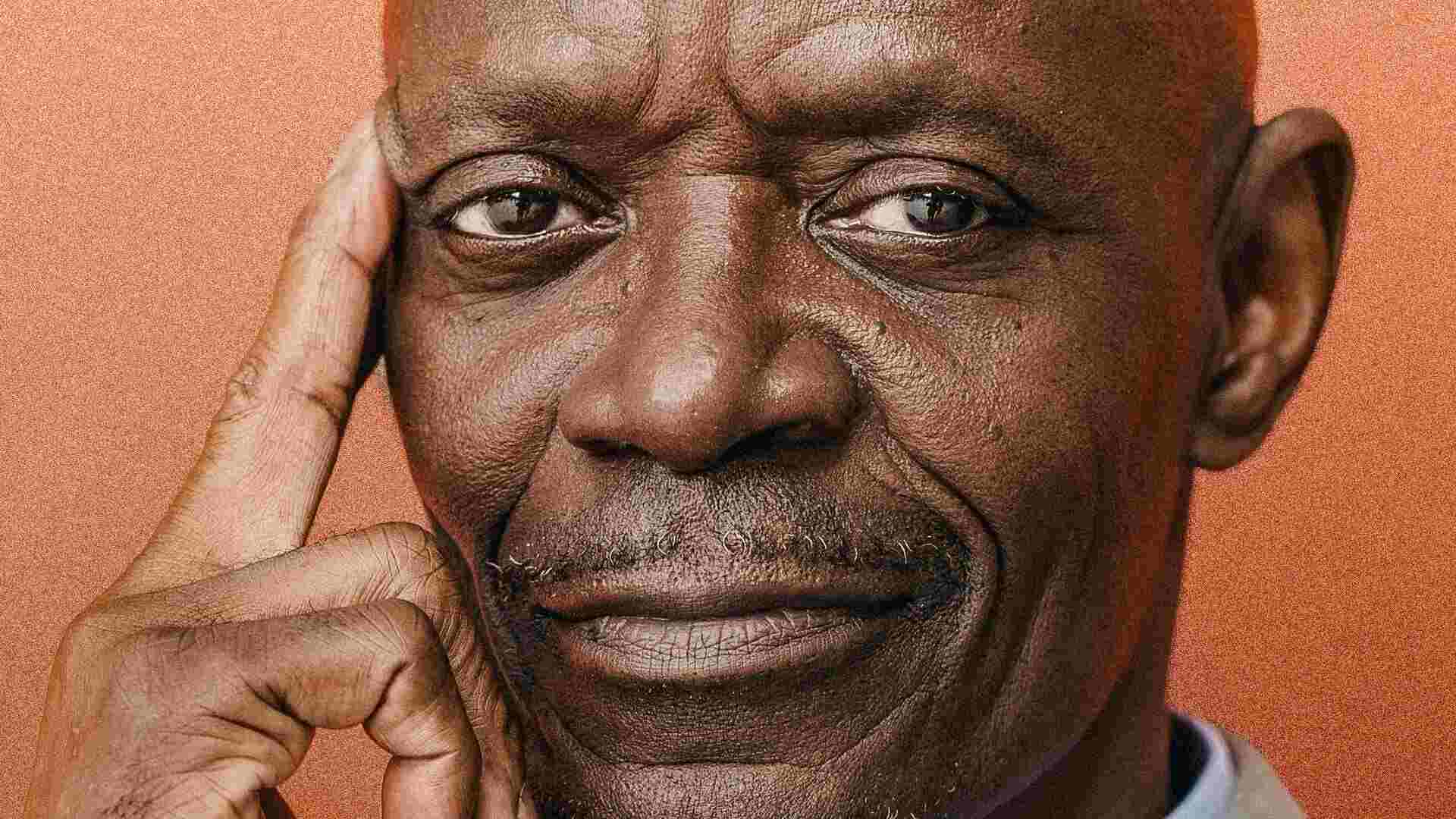

BP: When you understand an experience someone had, and are in a situation that echoes it, you’re more patient with their response. Let’s say your team member, Jason, is productive and reliable. Still, every once in a while he behaves differently in a meeting. If you know him, you might recognize that the presenter disrespected him. He introduced himself to everyone else. Then, because he was running late, never addressed him. If you know that Jason feels invisible as the only Black team member, and this man didn’t even acknowledge him, it’s much easier to understand how he’s functioning.

You can then help anticipate these situations. You can tell Jason beforehand: This guy has a dismissive demeanor. Don’t take it personally. When we can anticipate that a situation might echo one we’ve struggled with, we can avoid some of the negative parts of it. The human brain is a prediction machine. If you can help a friend or colleague’s brain make a better prediction, their brain is happier. We feel better when our predictions are correct, not when an experience is good. So, if you anticipated a bad experience, your brain thinks: It’s alright. That’s what I was expecting. Prediction helps us avoid dysregulating.

FC: Our relationships are the best predictor of how we handle stress. Challenges are inevitable in life and work. If you and I are working together, how can we strengthen our relationship, so we’re capable of buffering them together?

BP: We’re relational creatures. Our physiology and how we regulate our stress response system are intimately connected to our relational environment. When we feel connected to people around us—meaning they’re present, attentive, and responsive—that creates an environment of regulation and reward. Eye contact, a smile, a nod, all of these gestures positively impact a person’s physiology.

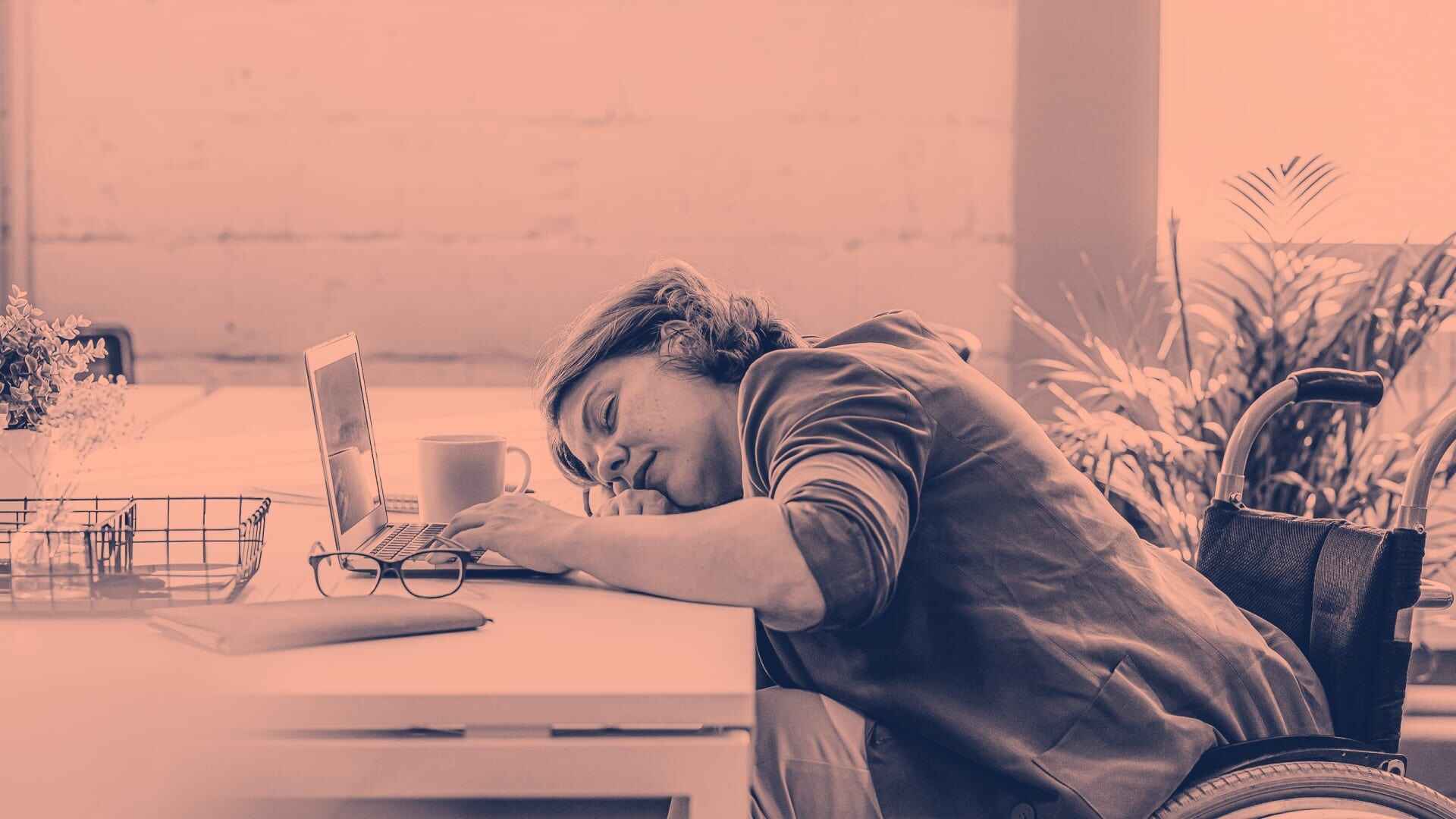

Picture a spiderweb. Each little strand is tiny. But, collectively, the web has tremendous strength. That’s what happens with these little moments. We don’t need to sit in a circle and hold hands all day. When you’re kind passing a team member in the hallway or offering feedback, you’re helping her weave her daily spider web of regulation. If only two of those strands are being woven a day, and somebody pushes you into it, you’ll break right through. This is what happens when people have relational poverty. They don’t have a strong fabric of social connectedness to protect them.

FC: You’ve emphasized the “untapped power of relationships.” How will tapping it help us realize our unexpressed potential?

BP: There were clusters of time, in places like Athens and Silicon Valley, when groups of intellectuals were gathered and patrons took care of their needs. These pockets of humans had bursts of ingenuity. We could create similar environments. The cortexes of humanity are like oil underneath the surface of the planet. We need to do brain fracking. And, not just the brains of the people at the top, like the world’s been a mirror of. We need a world that’s coming out of the cortexes of people with different histories, strengths, and gifts. Imagine if we did this across cultures and tapped the potential of billions of people’s brains.

FC: If you could leave us with one question to reflect on, what would it be and how would you answer it?

BP: I would ask: What gets in your way when you have an opportunity to connect and collaborate with someone?

The answer for me is often fear: Fear of whether I’ll be perceived as equal, if my ideas will be valued or I’ll get credit for them. Then, where does that fear come from? If you can look back and ask: What made me feel like I wasn’t enough when I was younger? Are those conditions still present? You can usually say: Not really, I don’t have much to fear at this point.