- | 9:00 am

A psychiatrist explains why calling everything toxic is bad for your brain

Many things are indeed deeply problematic and have gone on for far too long–on the other hand, plenty of situations where there are challenges are difficult without being toxic.

Language is powerful, and the words we repeat, the words we use over and over, shape individual and collective ways of making sense of reality, The words we use—and the associated ideas and concepts, ways of seeing and interpreting our experiences—concretely make up the reality in which we live, a philosophical position called social constructivism.

Not only that, but through consensual validation, we agree on what is real, both consciously and unconsciously. Nowhere is this more evident than in today’s social media-driven world, where trending ideas both capture and amplify the tenor of the times.

This can cut both ways, making useful ideas more dominant while running the risk of promulgating ideas that can be harmful or distorting. Especially when this happens under the radar—unconsciously—they are more dangerous because we don’t even know it’s happening.

There is a trend to use the label “toxic” more and more expansively: toxic people, toxic positivity, toxic relationships, toxic workplace, and so on. It’s everywhere. This is partly a good thing, because many things are indeed deeply problematic and have gone on for far too long. On the other hand, plenty of situations where there are challenges are difficult without being toxic.

THE ILLUSION OF TRUTH

There’s a phenomenon called the illusory truth effect akin to an optical illusion, where a scene appears on visual inspection to have properties that it in reality lacks, such as appearing three dimensional, moving when it is stationary, having spots where there are none, and so on. Illusory truth makes an idea seem true when it is false.

Essentially, if something is repeated over and over, your brain thinks it’s true. We see it a lot in politics, but it can be a tool for coercion and gaslighting by anyone. We hear the word toxic so much, it’s on the tip of our tongues so readily, that it may make it hard to tell what’s what. It’s critically important to reflect on what is influencing us to believe what we believe before deciding what we believe is true.

For physical reality, the rule-of-thumb that if something is repeated it is true works pretty well. And so we’ve evolved this capacity to predict and perceive reality as a function of repetition. The sun rises every morning, dark caves can be dangerous, seasons follow a pattern of temperature and weather (barring climate change), and the like. For social reality, things are mushier, and can be influenced. Social reality to a significant extent is what we make of it, whether deliberate, accidental, or under the influence of external messaging.

Hence, the term toxic—when used indiscriminately—is deeply problematic. There are several reasons, but the top line is that it is used so broadly as to become practically meaningless.

The main advantage to hitting the toxic button is that it is the safest way to make sure anything problematic gets flagged and bagged, However, by casting such a wide net, we run a significant risk of labeling things as toxic which are not poisonous. When situations truly are toxic, or are reasonably suspected to be harmful, it’s important to recognize it right away and take appropriate action.

BEWARE THE TOXICITY TRAP

There are several ways in which overusing the term toxic (and the unspoken concept of toxicity) can, well, be toxic. Here are some of the most important ones.

It’s too easy. There is a difference between when something is truly harmful to us and something which we don’t fully understand but feel uncomfortable with, even if deeply uncomfortable. There are times when our knee-jerk self-protective response is to label something toxic and then expel it from our lives and minds.

Sometimes, we are projecting—a term psychoanalysts use to describe how we disavow parts of ourselves by putting them on something external. We then may “split,” seeing ourselves as all good, and the object onto which we project as all bad.

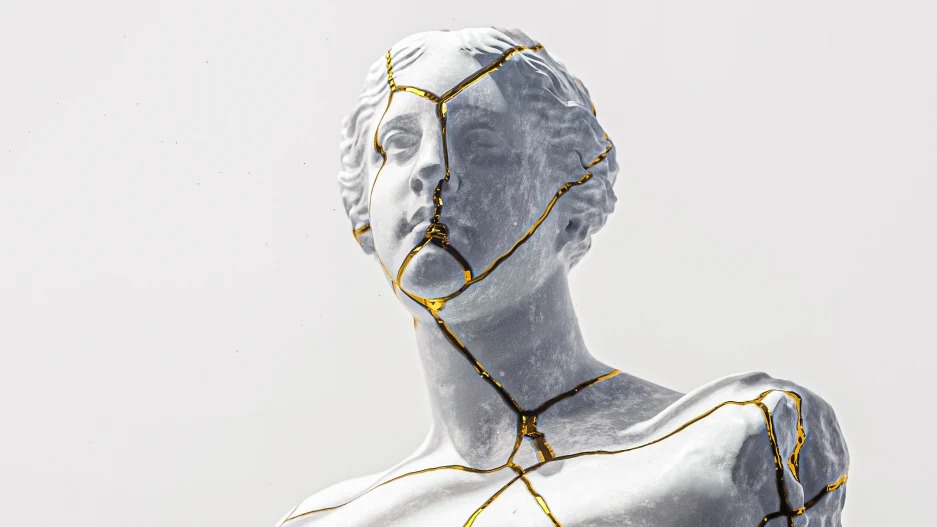

Missing out on opportunities. The broad use of the toxicity concept makes it all too easy to miss out on opportunities for personal reflection. However, if a situation is harmful, it’s important to recognize the reality of that and put a stop to the harmful elements. Sometimes this means hitting the eject button, but sometimes it means establishing new norms first, and seeing if change is desirable and possible.

When we apply the concept of toxicity too readily, we miss out on chances to repair ruptures in relationships and grow together, chances at work to figure out if a change is needed and approach it with more of a plan, and for personal growth (outlined below).

Misleading and inaccurate leading to distorted models of the world, relationships, work, oneself. The habit of mental violence, doing violence to one’s and others’ thoughts and ideas, to meaning itself, leads to no good. When we are feeling threatened, whether we are actually under threat or not, our capacity to think clearly is impaired.

Risk communication models, such as those discussed by social psychologist Vincent Covello, tell us that when under significant stress, our intellect drops. On average, we function four grades below our highest educational level, and are unable to process information beyond a few simplified ideas at a time. When toxicity is on our minds all the time, a sense of threat is omnipresent, leading us to internalize fear and aggression in ways which can mess up our ability to assess situations and make good decisions.

Interfering with compassion and resilience, undermining progress and healing. The toxicity lens likewise conjures up a sense of reality in which life is hell, other people are bad actors until and unless proven otherwise, and institutional entities like business, government, and schools are either malign, incompetent, or both.

In the extreme, being overly vigilant (the psychiatric term in PTSD is hypervigilant) for threat creates mistrust, paranoia, and makes it impossible to have room not only for clear thinking, but also feelings of kindness and compassion for oneself and others. Kindness is seen as weakness, compassion as a way to needlessly open oneself up to be taken advantage of by predators.

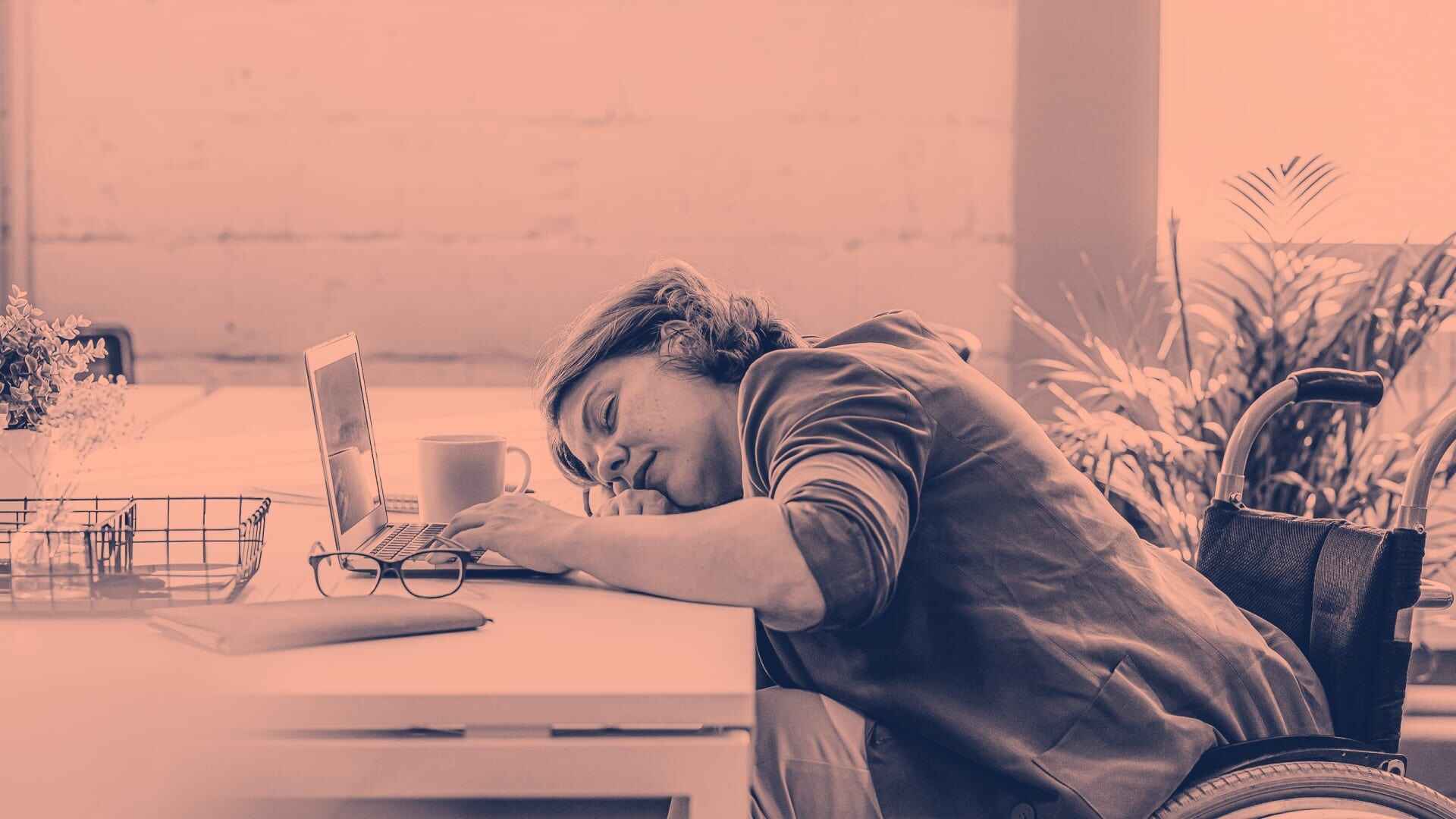

Resilience is based on mental flexibility and active, adaptive coping. Living in an environment which is perceived to be toxic (when it is not toxic—actually harmful environments, again, are a different story) is conducive to burnout as recovery: Growth and resilience mechanisms are hijacked by threat and survival-based systems and thinking. Such survival-based responses are meant to be short-term–they deplete resources quickly, and without recuperation don’t get re-provisioned.

Undermining self-compassion, leading to rejection of feared or disliked but needed parts of oneself. Living in a world defined by vigilance for toxicity leaves us at risk of undermining ourselves, both our concrete personal and professional goals, and also in terms of developing and sustaining a healthy and robust sense of self. If we are on a witch-hunt for toxicity in the world, there is a good chance we are also targeting and seeking to annihilate parts of ourselves which don’t immediately make us feel good, or which induce feelings of discomfort.

In Interpersonal Psychoanalysis, Harry Stack Sullivan notes we all need to be aware of “good me, bad me, and not me” for full self-recognition and development. It’s a process over time, especially with the “not me” parts, which are most frightful.

Likewise, Carl Jung discusses the importance of shadow work with aspects of the psyche and personality. Over time, we develop the ego strength to face, embrace, and own troubling elements in the psyche which we nevertheless need for creativity and thriving.

Eroding the common good by undermining trust and mutuality. The knee-jerk “experience-toxicity-and-totally-reject” makes sense in some circumstances (when elevated threat is probable), but as grand strategy fails by both making it impossible to think properly, and by undermining collaboration and making everyone seem like a possible enemy.

As such, the overuse of the toxicity concept leads to bad judgment and bad faith. There is a classic model from Game Theory called the “Prisoner’s Dilemma.” In this model, two people commit a crime together. They agree beforehand if they are captured, that neither will rat out the other person (defect). Rather, they will stick to the story.

However, law enforcement separates them right away, and starts undermining trust, currying doubt. In addition, law enforcement sets it up so that if one defects and the other keeps the faith, the one who stays true gets punished much more severely. If they both keep the faith, it’s best—but what are the chances of that happening? If they both defect, it’s not as bad for either as if one does and one doesn’t. So, it makes sense to defect—and that is commonly what happens.

However, if you play this game over and over, mathematicians have shown that cooperation is the best long-term strategy. In an environment laced with ambient fears of toxicity (and other things like gaslighting), it’s much harder to use the winning long-term strategy, because threat and mistrust dominate.

Rather than remaining a useful term which can be used to make thoughtful, reflective appraisals and wise decisions, the concept has become another arrow in the quiver of cancel culture. Anything labeled toxic is to be gotten rid of, negated without reflection or critical thinking. As such, it leads to division and siloing, furthering the echo chambers in which we increasingly reside, at our increasing peril.