- | 8:00 am

Failures can lead to success. Scientists help you predict which ones will

Using an evidence-based model for decoding failure, the ROI of errors is dependent on five key factors.

It has become a bit of a cliché to encourage people to “fail fast” and promote a culture that “celebrates failure” or rewards those who take big risks.

There are two problems with this.

First, it is mostly just lip service, like when a manager says that “people are their greatest asset.” There’s a reason such phrases have become the standard joke of work-related parodies, like The Office.

Second, there is no guarantee that failure will be of any use at all.

In fact, as illustrated in Amy Edmondson’s brilliant new book, Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well, which provides an evidence-based model for decoding failure, the ROI of errors is dependent on five key factors.

EXPLORE NEW TERRITORY

Did you actually venture into a new field, realm, or domain? Your mistakes are worth more if you make them in unfamiliar settings because they increase the probability that you will learn something new (more on this in the fifth point).

Let your curiosity take you to novel, unchartered territories, where, by definition, learning opportunities will abound. Although this may sound obvious, it is actually counterintuitive because humans have a natural tendency to optimize the world for efficiency, minimize thinking efforts, and stick to what’s familiar.

This is how most people tend to become an exaggerated version of their former selves, when in fact proper self-improvement and personal development requires learning how to go against our own nature.

One of the best measures of creativity is appetite for change, even when it is counterproductive in practical terms. For example, creative people are more likely to agree with the statement: “I take a different route to work everyday,” included in some creativity assessments. This isn’t pragmatic, at least not in the short term. However, it provides a wider and richer range of opportunities to encounter—and welcome—smart errors.

MAKE GOALS MEANINGFUL

If the “how” or territory of smart errors is unscripted, and even benefits from freedom, uncertainty, and experimentation, the “what” part of your pursuit should be rather set and determined a priori. That is, your failures will be smarter if they are aligned with a meaningful goal, or true opportunity to advance toward what actually matters to you.

Sadly, too many people engage in risks and experimentations based on the irrelevance of the downside, as opposed to the importance of the upside. So, if you find yourself doing something because you have nothing to lose, that means you will probably have nothing to gain either. In contrast, if you devote yourself to something because you have a lot to gain, then chances are you cannot lose because even your failures will teach you a lesson.

This logic is nicely captured in one of my favorite explanations of expertise, namely Niels Bohr’s observation that “an expert is someone who has made every possible mistake in a narrow field.” The key is to stick to the field that actually matters to you.

Although you can be uncompromising on the what, it’s best to be totally agnostic on the how. Your failures will completely reframe your what, but you need to have a clear goal at the outset. As the Cheshire Cat explained to Alice in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, if you don’t know where you are going, any road will take you there. But by being specific about where you want to go, you discover interesting new roads. Think of Christopher Columbus, who “discovered” America by trying to find a quicker route to Asia.

HAVE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

Smart failures don’t come by accident. They are the result of spending a great deal of time preparing for success but being surprised by the opposite. So, just as luck favors someone who is prepared, bad luck can be mitigated if you do your homework to reduce the probability that it will occur in the first place.

In the words of Daniel Kahneman, “Courage is knowing the odds and taking a chance.” This is why “reckless risks” can be avoided if you actually have some prior knowledge of the probable or potential outcomes of your actions. In that sense, expertise is critical for turning failures into useful experiences, illustrating the idea that “experience is what you get when you didn’t get what you wanted.”

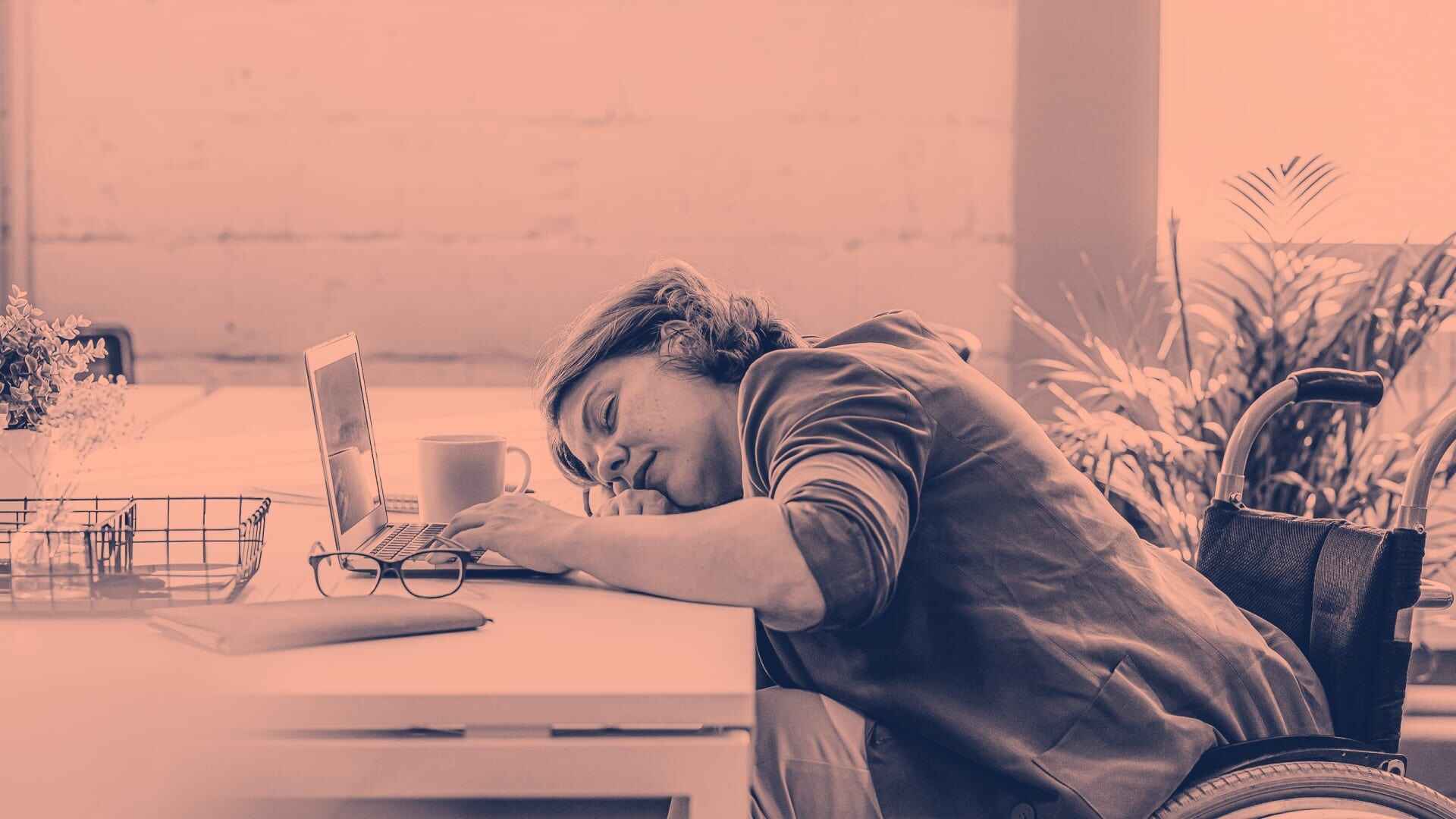

THINK SMALLER

Although motivational mantras such as “go big or go home” certainly sound uplifting, the science of failure suggests that you are much more likely to profit from your mistakes if you err small.

Small mistakes can make an incremental contribution to increasing your knowledge and experience, getting you closer to your goal. This also means managing impressions and keeping appearances, such that you never overpromise, overcommit, or over-risk with bold assaults on the status quo but, rather, quietly test things in private. This will also minimize the PR wounds that public failures or mistakes tend to produce.

As Amy Edmondson writes in Right Kind of Wrong: “One way to mitigate the reputational cost of failure is to experiment behind closed doors.” If you’ve ever tried on a bold new style of clothing to see if it suits you, you probably did it behind the door of a store’s changing room. Similarly, most innovation departments and scientific labs are private, with scientists and product designers trying all sorts of crazy things without worry of an audience.

MEANINGFUL LEARNING

Rather than a fifth or final dimension of smart failures, this is the ultimate prize: to end up knowing more than you knew before, and in turn be less likely to fail in the future. In a way, failure is always a better teacher than success because success reinforces our sense of confidence—which can lead to overconfidence and even delusions of grandeur. And there’s no better feedback one can get than the brutal realization that we are not as good as we want to be.

Our mind comes equipped with a wide range of self-serving biases and tricks designed to cushion the blows of failure and protect our egos and self-esteem. As Edmondson writes, “Self-reflection, humility, honesty, and curiosity propel us to seek out patterns that provide insight into our behavior.” Without these traits, you may not even interpret your mistakes as such, which is of course the biggest mistake one can make.

Since nothing that is of any value to human society or civilization has ever occurred without the effective collaboration of humans—a group of people being able to work together as a team—you must remember that whatever personal cost you incur for making mistakes, it may have enormous benefits for others. History is replete with examples of individuals who failed to extract critical learnings from their errors, inadvertently paving the way for future innovations by others.

This is how science proceeds: incremental improvements to the status quo, additive attempts to disprove or refute theories and hypotheses, and finding better ways of being wrong. As a species, we have this wonderful ability to learn from other people’s mistakes—even when we are reluctant to learn from our own. Your failures, then, may be other people’s successes, which makes intelligent failures remarkably altruistic.