- | 10:00 am

How companies can solve the mental health crisis happening in the workforce

The perks that may have once seemed optional are now essential.

Like so many entrepreneurs, Cesar Carvalho started his company to serve his own needs, betting that a lot of other people had the same problem. In 2012, Carvalho was a McKinsey consultant, working everywhere from his office to his home to on the road serving clients. He wanted a wellness solution that would integrate into his hectic schedule while allowing him access to gyms and classes that catered to his physical—and mental—health. So he cofounded and is CEO of Gympass, which grants employees of subscribed businesses access to not only workout classes, but also wellness services, including nutritionists.

Eleven years later, Carvalho and Gympass’s mission is more relevant than ever. According to the new McKinsey State of Organizations 2023 report, 90% of organizations are embracing hybrid work. But more importantly, the company is also at the center of another trend: 9 out of 10 organizations offer some type of wellness program to employees. Benefits can include yoga classes, mindfulness and time-management workshops, paid subscriptions to meditation apps, or even extra days off from work for mental health care. Most employees are affected by mental health challenges in some way, according to McKinsey’s report.

That’s why systemic interventions that encompass the entire workforce are required, instead of individual solutions. “Physical activity is important for mental health. Nutrition is important for mental health. Sleep is important to mental health,” says Carvalho. “The solution to the mental health crisis has to be holistic. Organizations can’t solve it with a spot solution for individual employees.” Companies ranging from conglomerates to startups are incorporating different solutions to improve their workers’ physical and mental well-being in an effort to keep them feeling good and working well. The U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s 2023 report, Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation, comes to similar conclusions: “Consider the opportunities and challenges posed by flexible work hours and arrangements (including remote, hybrid, and in-person work), which may impact workers’ abilities to connect with others both within and outside of work. Evaluate how these policies can be applied equitably across the workforce.”

PHYSICAL ATTRACTION

Gympass represents one type of systemic intervention. Employers pay Gympass a flat fee for access to an app, which allows workers to pick from different well-being plans. Through these, they get access to several in-person gyms and studios, other health apps such as the meditation service Calm, and even nutritionists. Google and Morgan Stanley signed up early on.

At the consumer-packaged-goods conglomerate Unilever, VP of human resources Matt Price says that the well-being of employees is tied to success in business. “We recognize that care of our workforce is paramount for business success,” he says. “That involved taking care of their physical and mental well-being.” Unilever has on-site gyms at its headquarters in New Jersey and also provides access to regular medical checkups for employees at its manufacturing facilities. At the same time, the company provides gym reimbursement to employees who may prefer to work out at home. “I think the world of progressive flexibility is serviced by a portfolio of services that understands the demographics of their workforce. We want to meet them where they’re at and where their needs are,” Price says.

Smart-ring company Oura has started partnering with companies to give them some insight into their employees’ physical well-being. Through Oura for Business, which launched in December, company partners provide their workforce with Oura rings, which measure sleep, heart rate, and activity. Executives can then see how a group is performing (all data is aggregated and anonymized) and make decisions based on team energy levels. “We have the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Air Force working with us,” says Dorothy Kilroy, Oura’s chief commercial officer. “They think about group level performance. They are concerned about team fatigue and burnout. They care how a group looks in terms of readiness or performance. That’s particularly important for scheduling decisions, as you could imagine.”

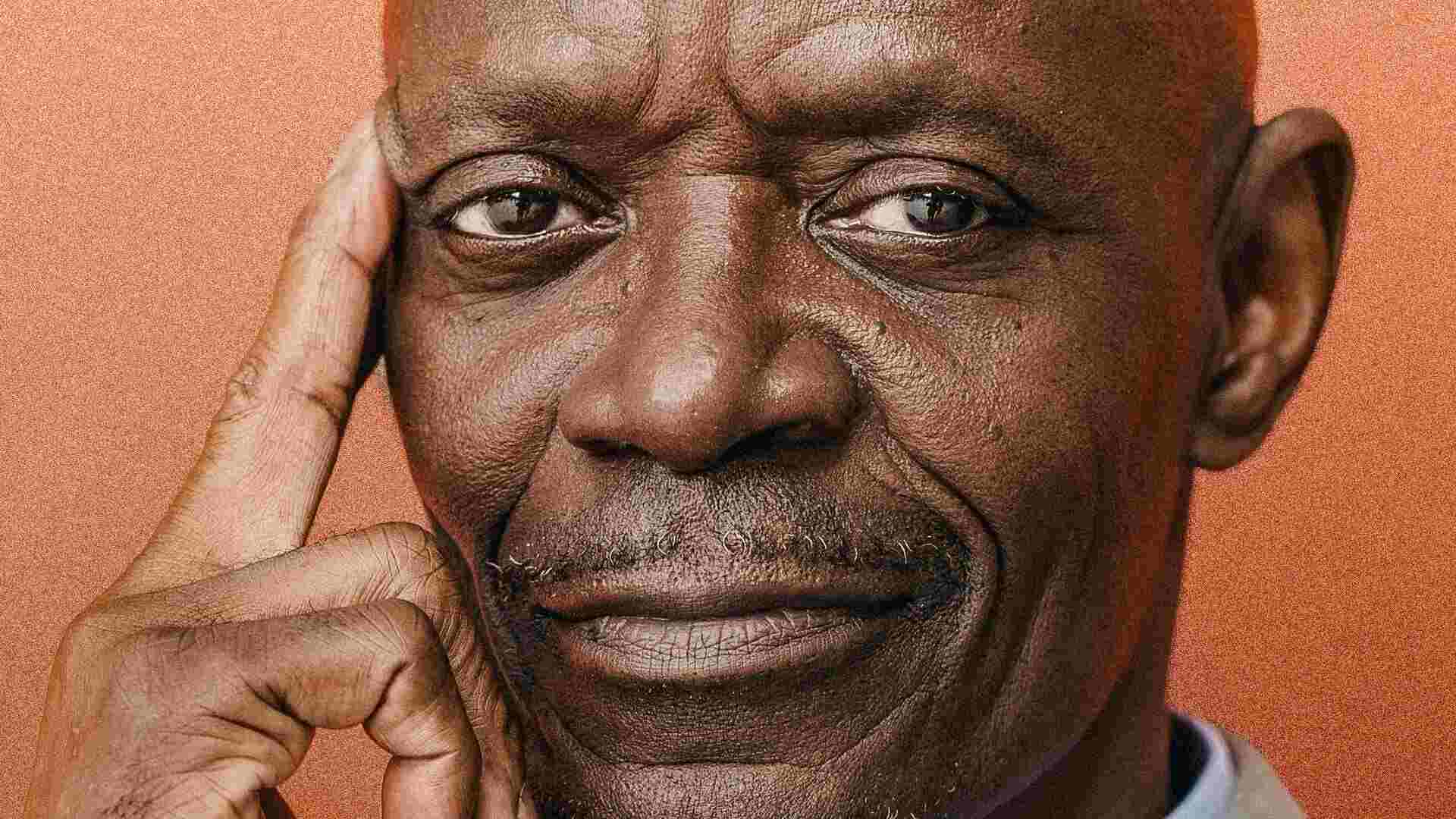

MENTAL MAGIC

While physical activity can improve mental health, companies are also providing dedicated resources to tackle mental health challenges. At Unilever, employees are provided access to mental health apps. Price also mentions the company’s proactive listening program for spotting potential issues early. “Mental Health Champions are like first responders for employee mental health,” he says, citing the company’s initiative. “They are volunteers who serve as a trained listening ear and identify any potential trouble spots and can refer people to employee-assistance programs we have.”

The company has also taken measures beyond remediating symptoms of mental distress as they pop up. Unilever has made it a priority to give their employees time and space in their schedules: Meetings are strongly discouraged on Wednesdays, and the office is closed on Fridays so that employees work from home. (This was long the case prior to the pandemic.) Price views these programs as a business imperative. “There’s a war for talent. Employees have a lot of choices,” he notes. “Organizations that are very responsive and thoughtful about a portfolio of services to help employee physical and mental health will have a unique advantage of attracting and keeping great people.”

Oura’s Kilroy says that employees having the kind of information that Oura provides can use it to help make better decisions for their mental health. “When they have an Oura ring,” she says, “employees can manage their own stress and their own burnout as well because they have access to data.” Employees can use their readiness scores to decide when to take time off or how to approach their work and interactions that day.

Still, even Oura sees barriers to adoption. While many companies offer access to wellness apps, employees don’t always end up using them. “You actually have to take an action to go and sign up for the program and get the app on your phone and actually start using it and start building a habit around using it,” she says, noting that she believes that Oura allows for users to build a routine once they start wearing one.

Her point illuminates the ultimate takeaway for every business that is focused on tending to its employees’ overall well-being. The best measure companies can take to protect employees’ mental health seems to be the one that employees are most likely to take advantage of—and stick with.