- | 9:00 am

How ‘workism’ replaced religion

Author Derek Thompson argues that ‘workism’ increases academic anxiety among children, worsens economic anxiety among adults, and creates a ‘leaky’ workday in which people feel compelled to work at all hours of the day.

Over the past several decades, Americans have become less religious. Pew estimates that in 1990, about 90% of Americans identified as Christian, 5% identified with another religion, and 5% had no religious affiliation. Today, just 63% of Americans identify as Christian, around 8% identify with another religion, and 29% say they have no religious affiliation at all.

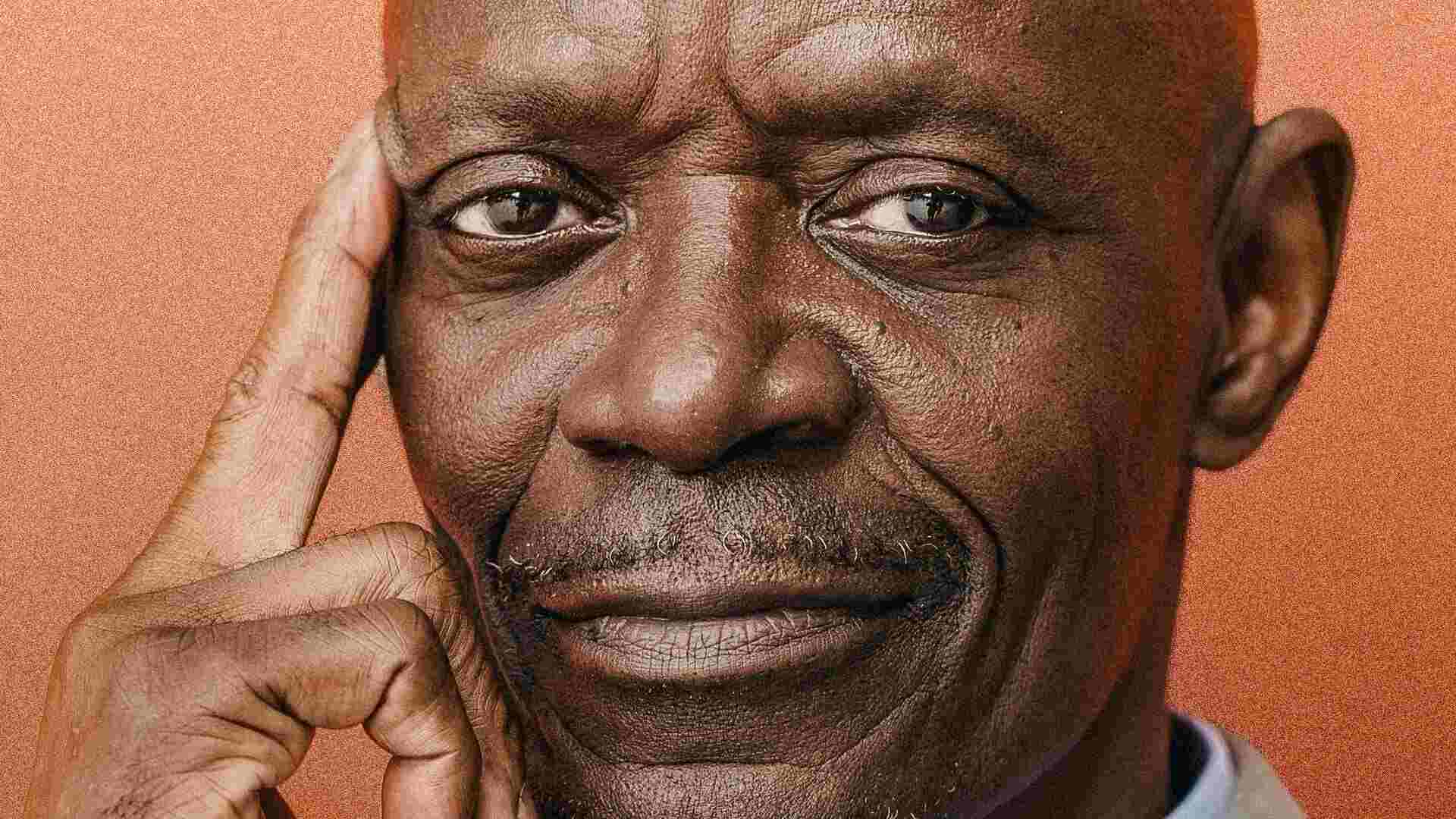

Journalist Derek Thompson’s new book, On Work: Money, Meaning, Identity, explores how work fills the role that religion once played in the lives of Americans, and why this new “workism” may be causing burnout.

The book, an anthology of Thompson’s articles for The Atlantic, includes a new adaptation of his essay on workism, a term that he defines as “the belief that work is not only necessary to economic production but also the centerpiece of one’s identity and life’s purpose.”

Ultimately, Americans’ priorities can be measured by how they spend their time, Thompson argues. In 2022, just 30% of Americans attended church or synagogue during a given week. On the other hand, 76% of Americans went to work during a given week.

“The decline of traditional faith in America has coincided with an explosion of new atheisms,” Thompson writes. “Some people worship beauty, some worship political identities, and others worship their children. But everybody worships something. And workism is among the most potent of the new religions competing for congregants.”

To explain why so many people have replaced religion with “workism,” Thompson loosely references David Foster Wallace. “If you knock off God at the top of the pedestal, you still have to put something there,” he says. “Everyone worships something.”

THE THREE PILLARS OF “WORKISM”

Thompson argues that “workism” has three pillars and numerous potential negative side effects. The pillars include the suggestion that people use work to provide what religion previously provided, that people expect more from companies (such as a sense of community), and that while devotion to work can make us productive and give us meaning, it can also overextended and exhausted us.

He fears that on an individual level, “workism” increases academic anxiety among children, worsens economic anxiety among adults, creates an often “leaky” workday in which workers feel compelled to work at all hours of the day, and exacerbates loneliness among retirees.

More broadly, Thompson warns that “workism” negatively impacts public policy.

“I’m afraid that America as a culture centers work too much in policy; we are one of the only countries in the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) without sick leave or parental leave at the national level,” he says. “Even our most successful welfare programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit are very much tied to the workforce.”

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN OUR VALUE IS BASED ON OUR WORK

Perhaps Thompson’s most compelling concern is that “workism” places a bigger emphasis on work relationships (which are based on our value as workers and our ability to complete tasks) than on our personal relationships.

What’s more, he argues that “workism” leaves not just our jobs but also our senses of self vulnerable to artificial intelligence. If our value is based on our work, what happens when automation makes our work unnecessary?

Yet despite these potential downsides, Thompson says that he worries his critique of “workism” can come across as “overly judgmental,” and he concedes that religions also have the power to hurt individuals. Indeed, many organized religions have excluded LGBTQ individuals, harmed Indigenous communities, and committed various acts of violence.

“If there’s one thing I could change I would have been a little clearer,” he says. “Given all the problems that exist in the world, people loving their jobs a little too much is not such a huge problem.”