- | 8:00 am

In 2023, my team quit Slack for a week. Here’s what we learned—and what we should quit in 2024

Water & Wall, a financial communications agency based in NYC and Boston decided to detox from Slack.

Wrestling Slack, a primary communication tool, from the grips of my highly productive, chatty, and fast-typing coworkers was no easy task.

In June 2023, our PR firm sent our millionth Slack message. Then we asked the team to quit using it. Here’s why my team quit Slack for a week in 2023—and what we learned.

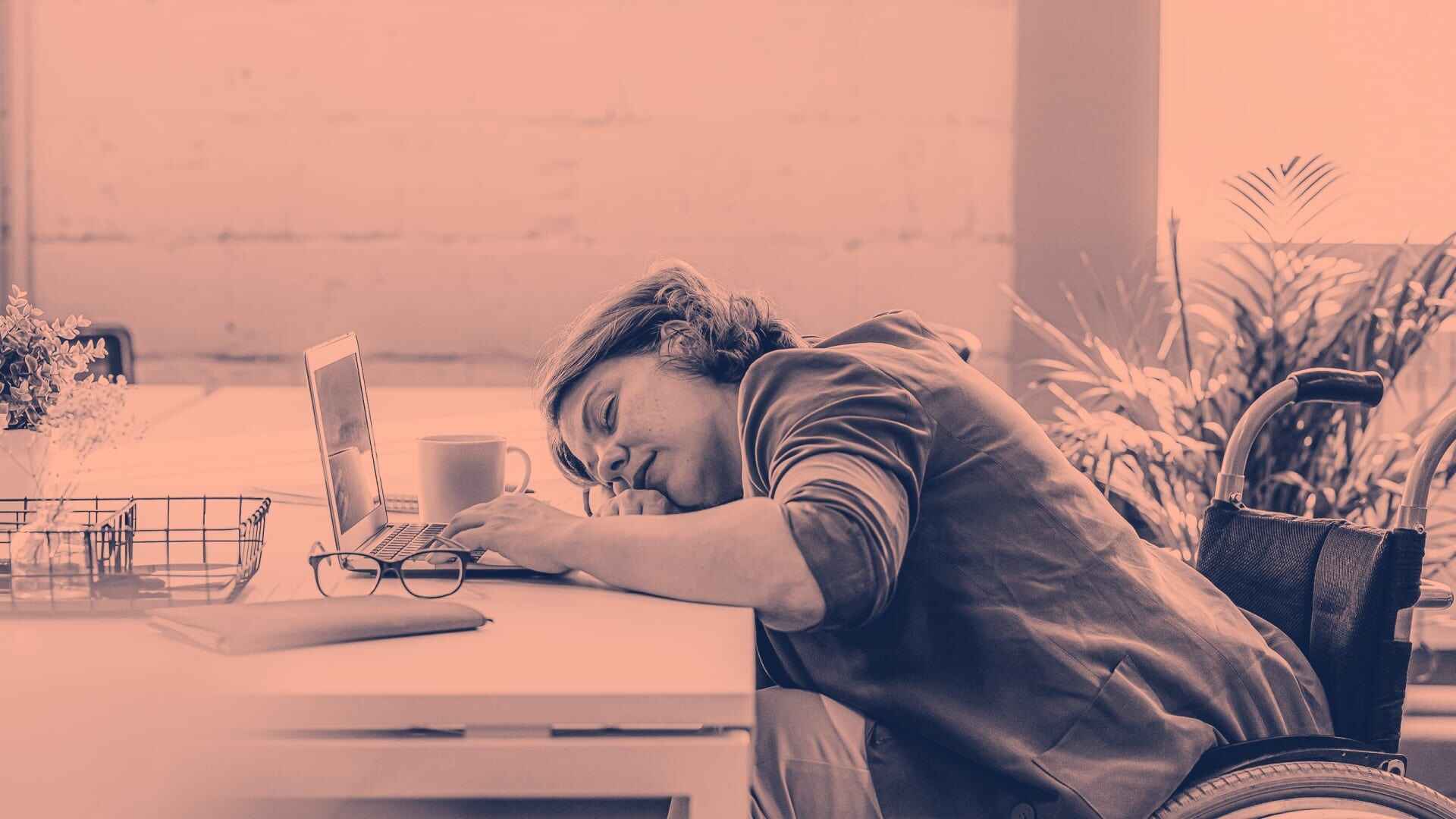

Our “Slack-out” was neither abrupt, nor was it carefully orchestrated. In fact, that was kind of the point. You see, we felt that the hybrid work model we had been beta testing had made us too reliant on written forms of tech-centric comms, namely when it comes to casual dialogue. Sure, Slack made complete sense when we were in lockdown, but over time it had grown to feel our reason for typing more to each other had devolved into an excuse to type more to each other. Besides, the Cleveland Clinic recommends we do a digital detox now and again anyway.

In 2019, Slack reported 12 million users. Back then, people met for coffee and most of us had to work in person in the same office. Today, Slack is estimated to have closer to 32 million users.

Our boutique public relations agency makes up just 10 of Slack’s 32 million users who rely on the platform for our daily work communications. The surprising thing we recently found is that the more we see each other in the office, the more we Slack each other. Yeah, it didn’t make sense to me either.

We’ve been on Slack since 2015. It started as an experiment with an AOL Instant Messenger-looking toy we didn’t think would have serious application to the day-to-day agency goings on. After all, “that’s what email is for” we said at the time.

Flash forward to 2023 and we had sent that millionth Slack message. We took a minute to think about what this meant for us in terms of how we work. What was fascinating to us about the volume of Slack messages we sent was when we ended up sending them the most. It wasn’t during lockdown. It was when we got into this rhythm of a steady office schedule. Usually, working from the office means group lunches, conversations about what’s going on this weekend, talking about the other people who have different jobs in our coworking space and how they hog the half dozen phone booths shared by hundreds of people. But we never realized that working in person was actually leading to us more online.

When we decided to detox from Slack, we surveyed our team. Here’s what we learned about ourselves:

- Half of the team said productivity increased because there were fewer distractions

- About 40% said that account teams weren’t as coordinated (though the work didn’t suffer)

- Instead of using Slack, 80% of us used text and email

- Only a couple of people met to work in person

We also found that it was harder to quit Slack than we expected. In fact, we failed at our own experiment miserably straight out of the gate. In the first five minutes on the first day of this trial, our CEO Slacked a teammate to update our quarterly report. The employee then Slacked their manager because he thought the Slack from our CEO had to be a trap. It wasn’t. Finally the employee reminded our CEO of our “Slackout.”

“Oops. I forgot,” Slacked our leader. “Sorry. Goodbye!”

Three out of four team members said they missed Slack, but that same amount said they’d be willing to try quitting again if there were clearer guidelines.

The point of the experiment was to see how we could manage without Slack. After all, we lived Slack-free before 2015 and we’ve got alternatives: email, text, and Microsoft Teams.

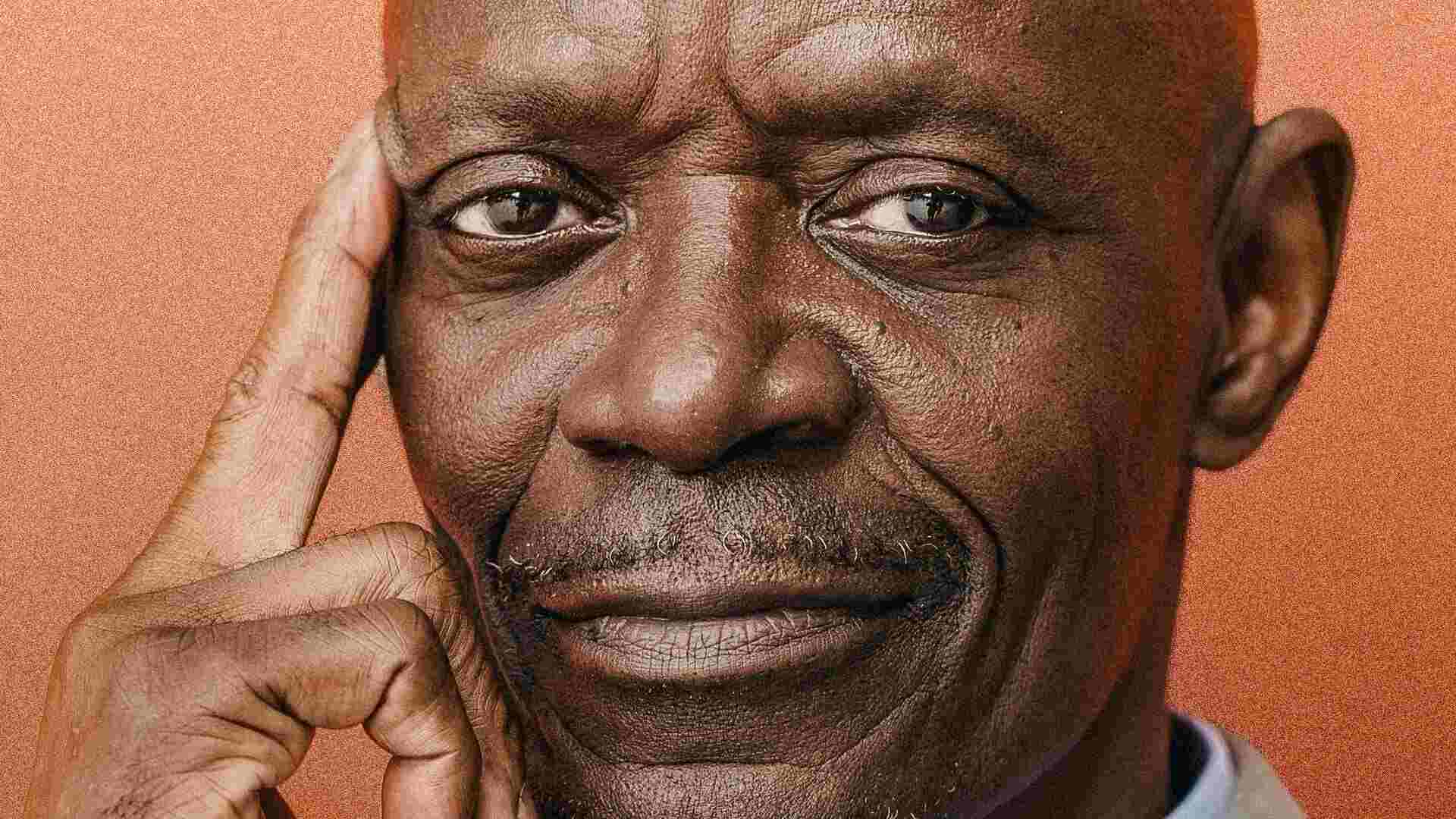

I talked to author Calvin Kasulke, who wrote the successful and aptly timed novel Several People are Typing. The entire book is written in Slack script. Its pages would appear no different than your Slack feed, save for the content of the messages. Though in many cases, maybe even that’s the same. I asked him about his book, about how humans work, and about our own experiment.

“Obviously being in person isn’t always feasible or even desirable, depending on the situation. But in terms of quotidian interactions, I think it’s worthwhile to switch up the platforms through which we communicate and see what we like best, or what works best with certain people or groups,” said Kasulke. “There are some friends I talk to on the phone or FaceTime more than I text with, and others who would only call me if there’d been some kind of catastrophe.”

He continued, “Analog communication and digital communication can coexist, but connecting in person will always have advantages the digital space can’t match—assuming the connection we’re talking about is a desired one.”

I asked Kasulke if he felt that people entrust each other with too much information now that we just write it to one another in rapid succession through mediums like Slack.

“Oversharing is possible, sure, but so is mutual vulnerability and a kind of accelerated intimacy. Some of my favorite coworkers are people I spoke to mostly over Slack and have met in person between two and zero times,” said Kasulke. “Humans are social animals. We want to share with each other. We’re going to communicate in whatever ways we can at almost every opportunity. But yeah, whether it’s on Slack or graffiti in a bathroom stall, I think people tend to get weird with it when they can’t see who they’re connecting with.”

Lastly, I asked Kasulke what is the next thing we should quit for a week.

“The funny answer is ‘email,’ the sincere answer is ‘uneven pay’ and to see what happens if everyone took home the exact same wages,” he said. “Both have the potential to create chaos, but the former might go over better if you tried the latter first.”