- | 8:00 am

The surprising benefit of learning to resist the urge to skip the tough stuff

To reduce the desire to skip life’s more challenging moments, try these three approaches.

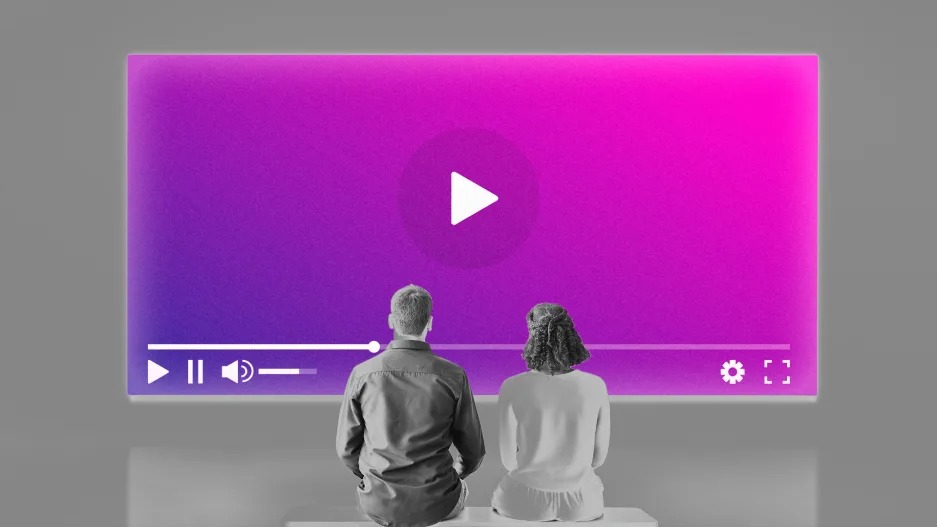

“What if you had a universal remote…that controlled your universe?”

The premise of Adam Sandler’s film Click is simple: The protagonist is granted a remote control that allows him to change the speed of his life (e.g., he can fast forward, slow motion, even rewind, etc.).

Spoiler alert: The protagonist fast forwards through the painful bits of life—eventually skipping decades in seconds—and realizes he missed out on most of the meaningful moments of his life. He learns his lesson and regrets it. He is granted an opportunity to go back to where he’d originally started in time, to live life again, without the remote. I watched it way over a decade after it came out, and though the details are foggy, the premise and fable resonated with me deeply.

SKIPPING THROUGH LIFE

As it turns out, Click was on to something. It was extremely profitable, earning over $240 million at the box office on a budget of a third of that. It said what we were all thinking. In What We Owe the Future, author William MacAskill mentions an unpublished survey of 8,500 respondents by psychologists Matt Killingsworth, Lisa Stewart, and Joshua Greene. MacAskill describes the survey:

At random times, they asked participants to write down what activity they were doing and how long it would last, and then respond to the question, “If you could, and it had no negative consequences, would you jump forward in time to the end of what you’re currently doing?” That is, they asked participants to imagine having the option of simply not experiencing—though still doing—whatever activity they were engaged in at that moment. If they were making a cup of tea, they would imagine that they could blink and their next experience would be drinking the cup of tea that they had just made. The researchers called this “skipping” an experience.

The results were surprising, at least to me:

The skipping studies were therefore somewhat skewed towards wealthier and better-educated people, and the results were not representative of the lives of prisoners, who in the United States constitute 0.7 percent of the population, or the homeless (0.17 percent of the US population). Yet, even within such a selected sample, participants said they would choose to skip 40 percent of their life, their bad experiences cancelled out nearly 60 percent of their good experiences, and, for more than a tenth of people, negative experiences outweighed the positive.

I found this study through Ali Abdaal, who writes in his Sunday Snippets newsletter, “How much of my day would I skip, if the things would still get done? Off the top of my head, maybe 30%.”

I could relate to Abdaal’s admission; if you’d asked me, I’d skip all of the soul-crushing business meetings, commutes and flights, the rushes to meet deadlines. That’s not to mention the health scares, the errands and chores, the conflicts, the creative blocks, and pretty much all administrative tasks. So. Many. Things. To.

Skip.

REDUCING THE DESIRE TO SKIP

Naturally, the idea here is, the happier you are, the less of your life you’ll want to skip. (I’d make the case this works the other way around too: if you want to skip less, you’ll be happier.) In his newsletter, Abdaal suggests three approaches to reducing the desire to skip:

Make it fun: If you’re doing errands, can you listen to a podcast, or music? Can you go grocery shopping with a friend? The term temptation bundling, originally from this paper by Katherine L. Milkman, Julia A. Minson, and Kevin G. M. Volpp comes to mind. (In a way, I feel like this is still a form of skipping.)

Avoid, delegate, or outsource it: This is the method preferred by startups and entrepreneurs: if it’s not adding value to your life, outsource it. Hire an executive assistant for administrative work. Hire a cook or chef to make your food. Sever a relationship, or just let it dwindle away.

Shift your mindset: Abdaal writes, “Ask yourself whether any experience is worth skipping (assuming it’s not painful or unpleasant). Maybe we should learn to appreciate the small stuff more, like going to the gym?” This is really the key; we can set up all the guardrails we want—sweeten boring tasks by making them fun, avoiding other boring tasks—but these are all temporary solutions. At some point, we will not be able to avoid some tasks, and we will need to decide how to make the juice worth the squeeze.

TINY, WONDROUS EXPERIENCES

In Four Thousand Weeks, Oliver Burkeman writes:

Geoff Lye, a British environmental consultant, once told me that after the sudden and premature death of his friend and colleague David Watson, he would find himself stuck in traffic, not clenching his fists in agitation, as per usual, but wondering: “What would David have given to be caught in this traffic jam?” It was the same for queues in supermarkets and customer service lines that kept him on hold too long. Lye’s focus was no longer exclusively on what he was doing in such moments or what he’d rather be doing instead; now, he noticed also that he was doing it, with an upwelling of gratitude that took him by surprise.

It doesn’t take a long cognitive jump to remember our mortality. The fact we even exist is a miracle in the first place. The possibility it could end at any moment is equal parts terrifying, and inspiring to soak it all in. That I’m typing this, that you’ll be reading it, is a happy miracle. In a happy linguistic coincidence, this moment is a gift; that’s why it’s called the present.

RESISTANCE IS FUTILE

One way to skip a long 16-hour flight is to watch four movies and fall asleep for eight hours. That’s not possible for me; I’m a light sleeper on planes, and my eyes are exhausted after even just one movie, I wouldn’t want to queue up the next. I tried powering through it once, as if I could dominate my body’s needs, only to experience a tension headache on the plane.

Message received. I didn’t have any painkillers, so I decided to do the only thing I could do: turn the screen off, drink some water, and sit there. The headache dissipated very slowly, and very surely.

This was a small revelation to me: time continued to pass by, I just had to keep my butt in the seat. I’d fortunately been practicing meditation for a short time already, so I just kept focusing on my breath. The passage of time continued moving forward, and by the end of the flight, I left with my mind feeling light and restored. One of my friends wasn’t so lucky; he watched a movie even during the descent, leaving him experiencing lethargy and nausea as we entered the airport.

Burkeman writes of a Steve Young’s exercise, one he had to experience in order to become a monk, in Four Thousand Weeks:

And yet as icy deluge followed icy deluge, Young began to understand that this was precisely the wrong strategy. In fact, the more he concentrated on the sensations of intense cold, giving his attention over to them as completely as he could, the less agonizing he found them—whereas once his “attention wandered, the suffering became unbearable.” After a few days, he began preparing for each drenching by first becoming as focused on his present experience as he possibly could so that, when the water hit, he would avoid spiraling from mere discomfort into agony. Slowly it dawned on him that this was the whole point of the ceremony. As he put it—though traditional Buddhist monks certainly would not have done so—it was a “giant biofeedback device,” designed to train him to concentrate by rewarding him (with a reduction in suffering) for as long as he could remain undistracted, and punishing him (with an increase in suffering) whenever he failed.

The desire to skip through these tasks is the same as the desire to resist that we even need to experience it in the first place. It’s natural to experience an initial resistance; doubling down on it, wishing we could skip through it, will only make it worse.

MAKE YOUR LIFE A CRAFT

In therapy, I was presented with a thought exercise: imagine that you had an occupation that you were born into for life. The occupation has to be one that is separate from your creative dream (in my case, writing books); moreover, it’s one that is very ordinary, mundane, and not particularly prestigious. Our session happened to fall on the day the garbage was removed, so we settled on waste removal; in this thought exercise, my parents and grandparents were all employed to collect garbage, and this was the family trade. I would be as well.

That sounded fine to me; I’d just write books early in the morning. Ah! But I’d need to get up at 4am or 5am to get ready for work, and by the time I’d gotten back, I’d be too tired to write. I’d want to unwind.

My therapist proposed that if we had me in two scenarios—one in which I woke up early to write books, and then went about my day, and the other in which I focused on doing my job and becoming the best garbageman I could be—the latter was the better one. I’d be happier and less angry (because I would’ve slept enough!), I’d take better care of myself, have more friends, and focus on my work while I was at work.

In the first case, which looks like me striving to become a really good writer, I was mentally skipping work while fulfilling the obligation of my physical presence. I’d be wanting to write books in my mind, while trying to do my job, which would be a stressful experience. I’d also be constantly worried that I’d lose my job, because I probably wouldn’t be delivering results or performing very well. I probably wouldn’t be particularly liked by my colleagues. I would be forcing myself to sleep early or late each weekday to try to write; I would be hard on myself—mentally pulling my own hair, trying to find a genius idea—any idea—that would create the situation I needed so I could stop working as a garbageman. I wouldn’t be looking for a situation in which I was skipping. (For the record, I could describe it this well because I literally did experience months spent like this.)

In the second case, which looks like me focusing on becoming a really good garbageman, I wouldn’t experience any overwhelming thoughts of what I was writing before work or what I need to be writing after work, or the notion that I should be busy chasing my dream; instead, I was doing what I was supposed to be doing. I was becoming a great garbageman, and making my work a craft. I would know how to handle cold winter days in Canada, I would perfect the technique of collecting garbage bags—efficiently and without injuring myself, I would get along with my colleagues and start to better understand the organization naturally.

This was a fascinating thought to me, and my therapist put the cherry on top: in the second case, I was likelier to write a good book (paradoxically, with less effort!) than in the first case. I was focusing on the foundation to make a good life out of the present, and not on trying to chase a dream in which I could skip the pains of this present life. I initally balked at this possibility (“Do you know how hard writing a book is?!”), but as I sat with it, it felt more right to me.

It created a second-order change in my head. My job is my job. The point is not to skip it, outsource it, or automate it. The point is to do a good job, and if any of those things support it, then that works. (This is story would go well with Patience is Power.)

The other point I came to accept: I’m lucky to have a job. (In my case, a job at a business that I also happen to own—a job nonetheless.)

APPRECIATING THE TEXTURE OF LIFE

Burkeman defines a problem as, “Something that demands that you address yourself to it—and if life contained no such demands, there’d be no point in anything.” As such, one surefire way to enjoy life is to develop a taste for experiencing problems. Because real life is just problems, all the way down.

Soak it all in. Everything. The good, the bad, the boring, the stressful, the enraging, the outrageous, the grief, the sickening, the disgusting, the envy, the joy, the elation, the wonder. Because this is it. Spiritual teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti once told his class, “I don’t mind what happens.”

Accept reality. Surrender to it. Easy words to say, not as easy to practice.

This article originally appeared on Herbert Lui’s blog and is reprinted with permission.