- | 8:00 am

What your company probably got wrong about its return-to-office plan

On this week’s episode of The New Way We Work Gleb Tsipursky explains why so many bosses and clashing with employees, why collaboration isn’t happening, and offers alternative ways to configure a hybrid work schedule.

We are over three and a half years into our collective experiment with remote work and while many companies started calling their employees back to the office over a year ago, a pretty big disconnect remains between what companies want and what employees want when it comes to where work gets done.

According to LinkedIn data, 50% of job applicants say they don’t want to be in the office full time and nearly as many (40%) of current employees say they would quit their job if their employer made them come into the office full-time. Meanwhile, the number of job listings that offer remote work has steeply declined: The peak for remote jobs was in March 2022, with over 20% of all job listings on LinkedIn offering the either fully remote or hybrid, compared to just 8% at the end of May 2023.

So, how can leaders bridge this divide? Is there a way to craft a return-to-office policy that makes both bosses and employees happy?

On the latest episode of The New Way We Work, I spoke to Gleb Tsipursky, frequent Fast Company contributor and CEO of the future-of-work consultancy Disaster Avoidance Experts. He wrote the book Returning to the Office and Leading Hybrid and Remote Teams. I asked him what works and what doesn’t in getting employees back to the office.

ONE SIZE DOESN’T FIT ALL

Tsipursky said that the most common hybrid approach—a blanket policy that requires all employees to come into the office a set three days a week—is actually the worst method. He says that the best approach to coming back to the office is a team-led model, in which management helps different teams and departments decide what makes the most sense for them.

“For example, think about your programmers. If they’re working on a typical two-week sprint, it might be helpful for them to come in only when they’re starting the sprint and when they’re finishing the sprint,” he explains. “Or for accountants, it’s much more important to be in at the end of a quarter. And so they will have a schedule where they will come in at the end of a quarter for maybe a whole week and maybe not come in during the middle of the quarter, or occasionally at the end of the month to close the books and not at all during the middle of the month.”

HOW EMPLOYEES ARE RESISTING RTO MANDATES

In the return-to-office battle, Tsipursky says he’s found that there are several ways employees resist return to office policies. The first is open public resistance, which is the kind that has made headlines recently at companies like Amazon, where employees have signed petitions, or walked off the job in open protest to the policies. A slightly less dramatic version of this is those who just refuse to comply, either they just continue to work from home or they only come into the office once in a while. He points out that most of the employees in this category are more senior and established in their roles, so they believe that they can get away with it.

Tsipursky says that managers who he speaks to say that they end up covering for these employees who are not coming to the office, because they don’t want to lose them, especially when the managers also don’t find the top-down rules to be helpful or relevant for their team.

The second way employees resist return-to-office polices they don’t like is simply to quit. These are employees who have talents that are in demand elsewhere.

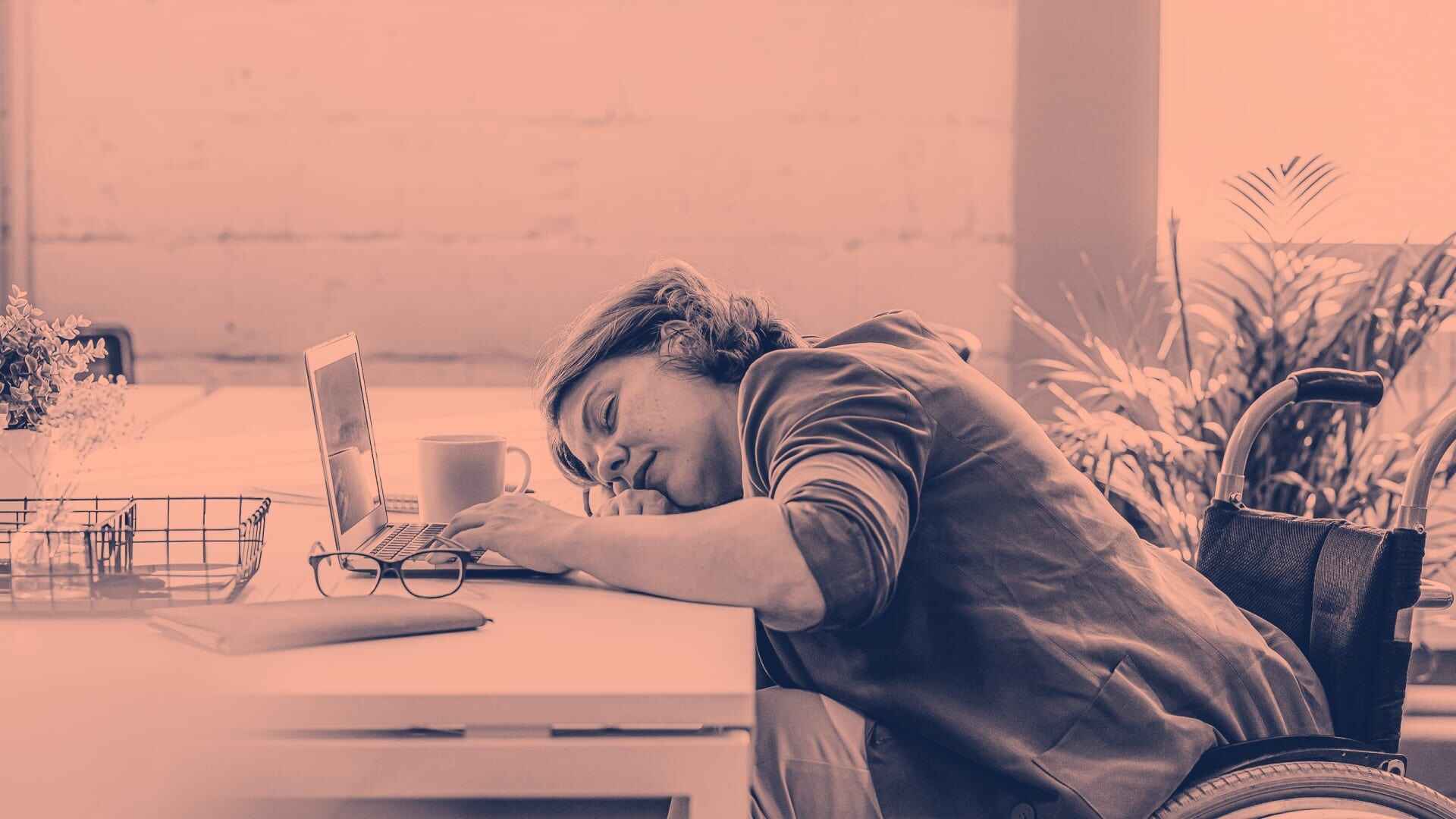

Another method of resistance, he says, comes from employees who are less established, or more junior employees who may not have as desirable skills, is to quiet quit or disengage from their work, complying with RTO mandates, but giving 80% instead of 100%. Tsipursky says that according to surveys he’s conducted, the people who are most disengaged are remote-capable workers who are forced to be in the office when they don’t want to be.

WHEN ENFORCING RTO POLICIES BACKFIRES

Because so many companies took a top-down approach to their RTO policies, and as a result employees who didn’t want to return have been resisting, some companies have responded by resorting to punitive measures, like tracking badge scans and using in office time in performance reviews. This obviously builds a culture of distrust and further disengagement. “What is really helpful,” Tsipursky says, “is conversations with your employees about why they should be in the office [and] getting on the same page about what the office is for.”

He suggests that company leadership first do surveys to get information from employees on how often and for what purposes they want to be in the office and from there they do smaller focus groups to go in depth on the surveys. Unsurprisingly, he’s found that the best things to do in the office are collaboration, socializing, mentoring, and team bonding.

For more on how to facilitate meaningful collaboration and socialization that isn’t cringe-y “mandatory fun,” and for more on how remote managers can help the career growth of in-office or hybrid employees, listen to the full episode.