- | 9:00 am

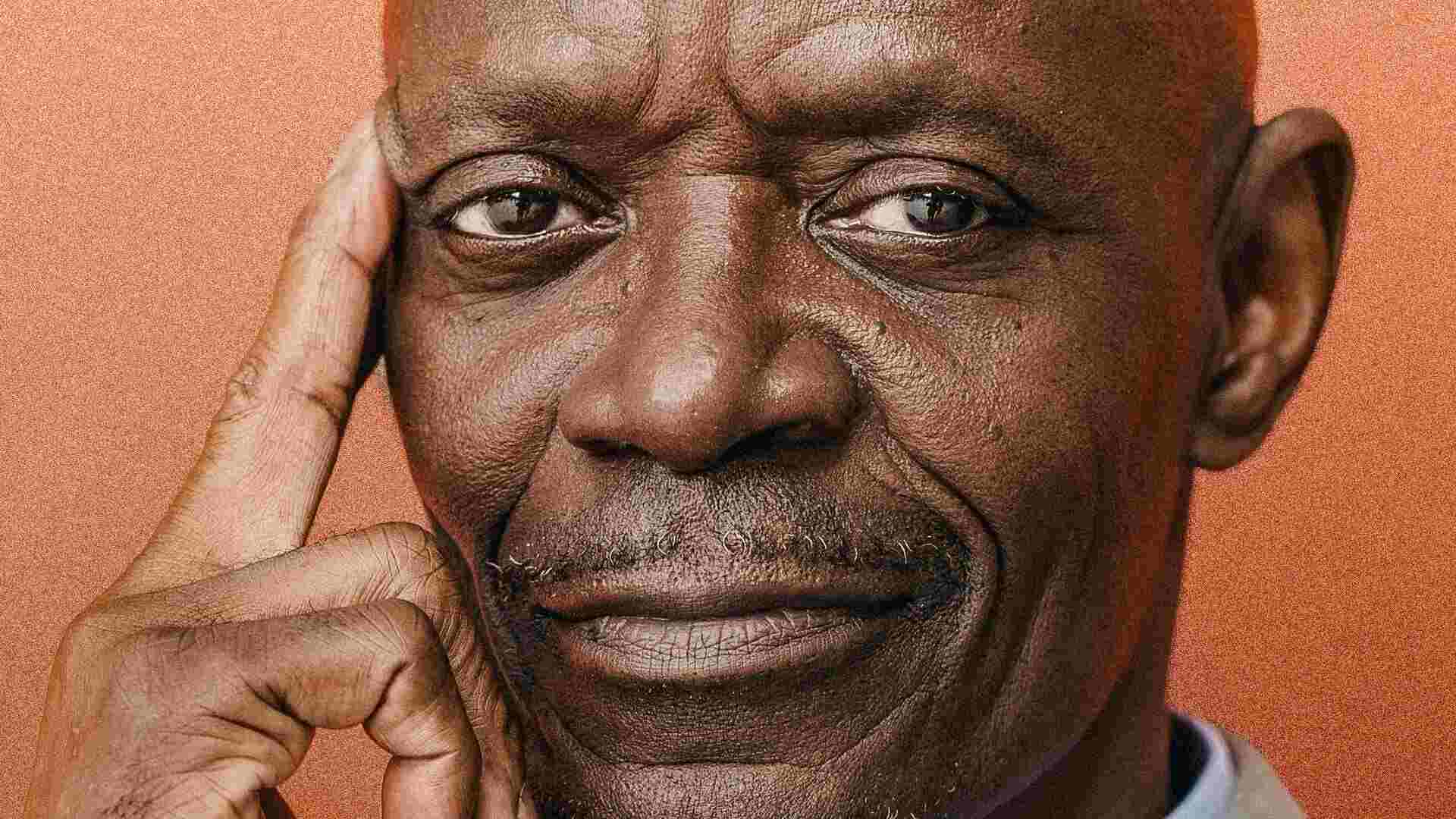

Why ‘geek’ companies are more successful, according to an MIT researcher

In his new book, Andrew McAfee, cofounder and codirector of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, explores what makes a successful corporate culture.

I’ve been studying how digital technologies change the world for almost 30 years, first at Harvard Business School and now at the MIT Sloan School of Management. During that time I’ve spent a lot of time at companies in both the “old” and “new” economies—in other words, at both the incumbents of the industrial era and at the new entrants clustered in Silicon Valley. I found that the two types of companies operate very differently, and that over time these differences didn’t fade; instead, they grew bigger. And they matter.

As the saying goes, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” I’ve come to believe that the most fundamental reason Silicon Valley companies are disrupting so many industries is that they’ve iterated and experimented their way into a corporate culture that supports high levels of agility, innovation, and execution simultaneously. I call this culture the geek way. It’s based on four norms expected by those around you (and not just the bosses). These norms are speed, or iterating quickly and getting feedback; ownership, or devolving responsibility and authority and de-emphasizing coordination and cross-functional communication; science, or conducting evidence-based debates about how to move forward; and openness, which is close to psychological safety and far from defensiveness. Of these, openness holds a special place because it sets up “community policing” of a company’s culture. People who feel comfortable speaking up help keep a company on track.

I saw the norm of openness at work firsthand at HubSpot, a Cambridge-based SaaS company that practices the geek way even though it’s far from Silicon Valley. An interaction I witnessed there showed me the geek way in action, and showed me how powerful it is.

In the summer of 2006 Brian Halligan sat down in my office at Harvard Business School and started asking me questions about an article I’d recently published. He had just finished the MIT Sloan Fellows program, a 12-month MBA, and was about to launch a company with classmate Dharmesh Shah. The article that had caught his eye was about using tools like blogs and wikis (the software that’s at the heart of Wikipedia) within companies, and he wanted to explore the topic more deeply. In our initial conversation, we learned that we were both excited about technology’s potential for making businesses work better, and that we were both Boston Red Sox fans. We formed a geeky bond, and stayed in touch.

By 2009, HubSpot, the marketing software company he and Shah founded, was growing quickly. Halligan was the CEO, and he came back to my office to talk about putting together in-house education programs for his employees. He wanted to give HubSpotters the chance to pick up new skills via evening classes. This isn’t unusual; most companies offer training. But Halligan went about it in a novel way.

I’d been teaching in business schools for a decade and had been part of many executive education programs. Company-specific programs typically occur because a top manager wants to, say, prepare her division for the internet economy and so reaches out to a business school. The manager and the school settle on a curriculum, and the program becomes reality.

Halligan took a different approach. After he and I brainstormed for a bit, he said, “Okay, come into the office; let’s present this idea to the HubSpotters and see what they think.” So we did. I found it one of the more eye-opening meetings of my career because of how Halligan interacted with his employees.

After he introduced me to the assembled group of about 20 people, I talked about the curriculum we’d been brainstorming. Then he talked about the skills he wanted HubSpotters to have. He finished with “So what do you think?” and sat down. In my experience, this was a cue for employees to tell their CEO that what they’d just heard from him was great, really the right idea at the right time, and they only had a couple of suggestions—building on what they’d just heard—to make it even better.

Instead, the first person to speak, who looked too young to have been anything except a recent hire, opened with “There are a couple things that I don’t like” and continued on. I felt a little bit sorry for the kid. Flatly contradicting your CEO in public might not be a career-ender, but it would at least serve as a teachable moment for him and the rest of the people in the room. Of course, Halligan wouldn’t respond with anything as obvious as “Watch yourself, youngster,” but would he take the usual approach of making a self-deprecating comment that everyone in the room would implicitly interpret as a warning? Would the other attendees rush in with “What I think you mean to say . . . ,” or “I hear a lot of agreement here!,” or any of the other standard lines intended to restore all-important harmony?

What actually happened was that Halligan said, “Yeah, good point. I hadn’t thought of that,” and continued from there. His body language didn’t change, the tension in the room didn’t rise, and no one except me looked the least bit surprised. When he and I met afterward to discuss what we’d heard, he didn’t mention the incident at all. To him, it was business as usual. He didn’t want the group to rubber-stamp his ideas or celebrate his munificence; he wanted an honest and egalitarian exchange of views on a topic. Which was what he got.

Halligan’s and Shah’s efforts to build a strong culture at HubSpot paid off over the years. In 2014, the workplace review site Glassdoor started publishing a list of the top small and midsize companies to work for in America, based on what the companies’ own employees said about them. HubSpot was No. 12 on the list. Two years later, the company had grown so much that it moved into Glassdoor’s large-company list, where it took the No. 4 spot. In 2020, Glassdoor named HubSpot the best large company to work for in America.

Excerpted with permission from The Geek Way by Andrew McAfee. Copyright © 2023 by Andrew McAfee. Used with permission of Little, Brown and Co., New York, NY. All rights reserved