- | 8:00 am

Why leaders should always listen first and speak last

In her new book, Hortense Le Gentil breaks down why leaders like Satya Nadella and Mary Barra prioritize listening.

The most effective human leaders are those who have successfully repositioned their role from quarterback to coach. Their job is no longer to handle the ball and score points; it is to inspire and support the players to give the best of themselves and make sure they play as a team so together they can score points. In other words, leading requires different attributes and behaviors than managing.

Learning how to move from one to the other is not easy: early in a career, success often depends on knowing how to be a good quarterback. In a leadership position, however, knowing how to ask questions is more important than coming up with answers. In The Coaching Habit, leadership coach Michael Bungay Stanier offers a framework of seven essential questions to change how we lead. Similarly, speaking last is more effective for leaders than volunteering ideas and opinions first. In other words, one of the essential qualities of effective human leadership is knowing how to listen. Becoming an excellent listener is critical not only in itself but also because it underpins other elements essential to being an effective human leader, such as empathy—more on this in a later section.

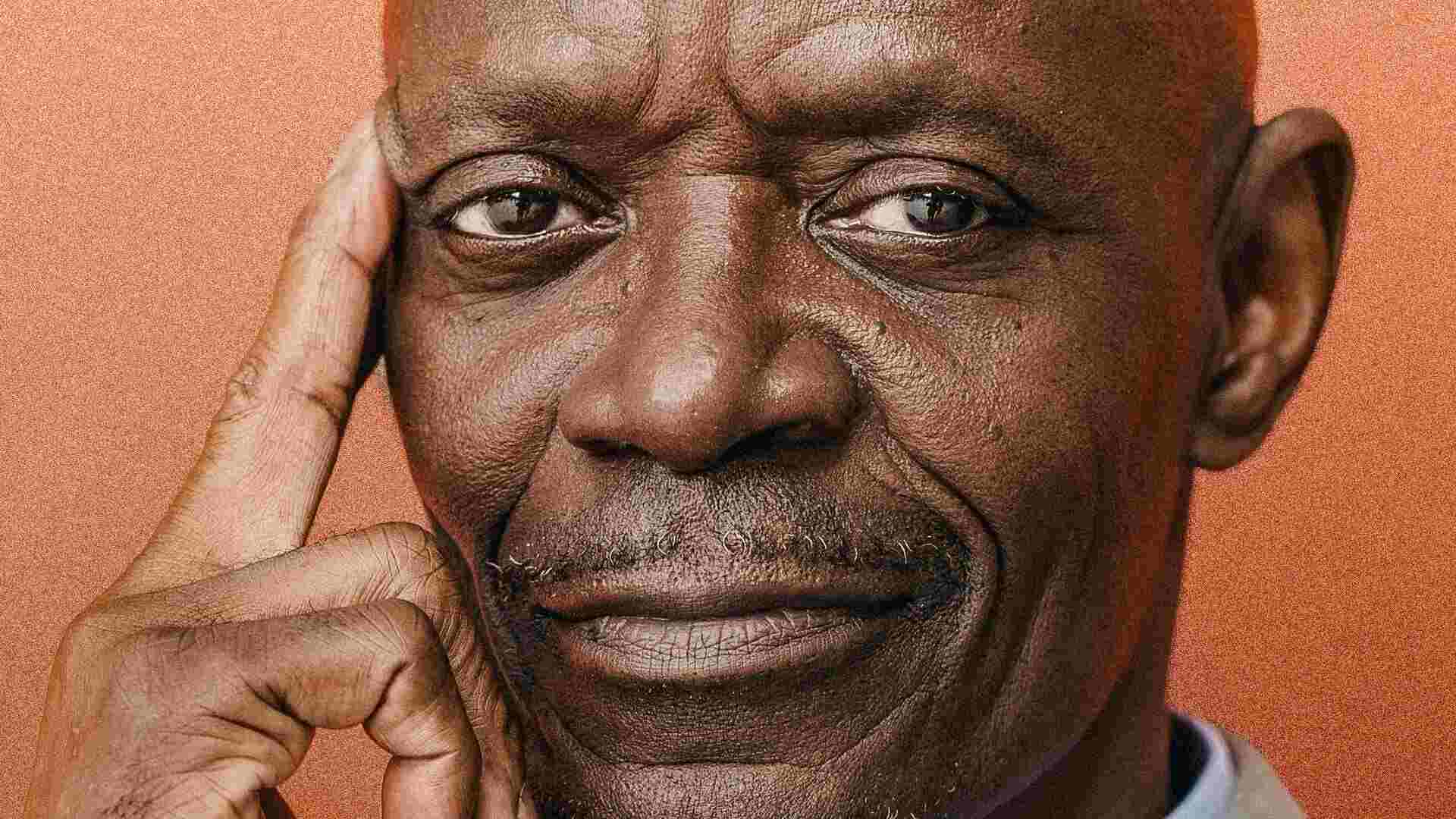

Hubert Joly experienced firsthand how hard it can be to make that transition from quarterback to coach. When he headed Carlson Wagonlit Travel, the head of human resources handed him a new org chart at a company party. The new chart was peculiar: the name that appeared in every box was Hubert’s. The joke was revealing, though. By his own account, Hubert Joly had been jumping in to solve his teams’ problem for years and, without even realizing it, telling them what to do. After all, wasn’t it exactly why he’d become CEO?

The problem was he hadn’t yet repositioned himself as a leader.

By the time he became CEO of Best Buy, the electronic retailing chain that was then on the verge of a precipice, Hubert Joly approached his role very differently. He spent his first few days on the job working in a Best Buy store, observing and asking everyone who worked there a lot of questions. He then mobilized a team of some 30 people from all parts of the business to create a turnaround plan. How did he approach his own role? Ask questions, listen, and create the right conditions so everyone could come up with answers together and co-create a plan.

He credits his change of approach to several things, including some coaching. But what also helped greatly was being an outsider with no experience in retail. He knew he didn’t know and had a lot to learn. There was no temptation to jump in and try to fix everything because he was new to the company and new to the sector. This is the silver lining of confronting multiple complex and unprecedented crises, as leaders do today: there is no expertise or experience to fall back on and contribute, which makes it easier to step back, reposition, and behave as a human leader. “It’s easier to say ‘I don’t know’ when we actually don’t know,” Hubert Joly points out.

How do we become better listeners?

As a child and teenager, Bob Dylan spent nights listening to anything that came out of the radio. There was R&B, jazz, gospel, and rock ʼn roll. But he was also fascinated by radio dramas. This is how he learned to listen to small, random, everyday things like a door slamming or the whistling of wind through the trees. “It made me listen to life in a different way,” he said later. “It made me the listener that I am today.”

Like anything else, changing behavior starts with intention and mindset: adopting a learn-it-all mindset rather than a know-it-all attitude, to borrow Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella’s words, goes a long way in helping shift our behavior from speaking to listening. Showing how much we know typically involves speaking; wanting to learn, however, shifts our behavior toward asking questions and listening. A learn-it-all mindset, coupled with the ability to listen, also helps human leaders own and acknowledge their own mistakes. Nadella, shortly after becoming CEO, was asked during a conference what advice he would give women uncomfortable asking for pay raises. His answer to “have faith in the system” instead of asking for pay rises unleashed a furore.5 His learn-it-all mindset, his authenticity, and his ability to listen meant he could quickly and easily acknowledge that he’d answered the question “completely wrong” and that he’d learned “a valuable lesson.”6 This signaled within Microsoft that no one, including the CEO, was expected to be infallible. Mary Barra, the CEO of General Motors, sums up this mindset: “It’s okay to admit what you don’t know. It’s okay to ask for help. And it’s more than okay to listen to the people you lead. In fact, it’s essential.”

Speaking last helps leaders become better listeners, too. This is what I often advise my clients who struggle to stop themselves from jumping in to fix problems that others are perfectly capable of handling if given a chance: turn your tongue in your mouth six times before speaking or count to 10.

As trite as it may sound, we learn to listen by speaking less, too, in addition to speaking last. Musician Greta Morgan found that out the hard way. In 2020, she was diagnosed with a rare neurological disorder that affected her voice permanently. She could no longer hold a note, her voice was wavering uncontrollably, and her vocal range had dramatically narrowed. For someone who makes living as a lead singer, this was devastating, and she experienced what she described as “identity death.” She retreated to Springdale just outside Zion Canyon National Park for a month to rest her voice completely. And as she stopped talking, something unexpected happened: she started really listening and realized how much more she could hear. “It was as if I had never listened in my life,” she remembers. It transformed the way she paid attention to the world around her.8

Learning to listen also means learning to be mentally present. Whenever we’re thinking about our last meeting or the next one, or checking our phones, we’re not properly listening, even if we don’t say a word. Learning to listen to others, really listen to them, requires complete focus. How can we do that when the human brain automatically produces a constant tsunami of thoughts? It takes practice. Mindfulness—in other words, being fully present—has been shown through countless studies to help us quiet our mind—and a quiet mind is a listening mind. This doesn’t have to be complicated: I often advise my clients to practice what I call the “close the door and open the door” exercise: at the end of each meeting, conversation, or activity, resist the temptation to jump straight into the next one. Instead, take a moment to close the door on what you’ve just done, so you don’t carry on thinking about it as you start your next conversation or undertaking. Closing that door could mean jotting down a few notes and thoughts or scheduling some time to think about it more so you’re able to set it aside and empty your mind. Or it could mean doing nothing more than taking a few seconds or one minute to bring your mind into the present, interrupting the flow of thoughts about what did happen or will happen or should happen.

It is sometimes helpful to associate this mental discipline with a ritual: it could be as simple as drinking a glass of water, walking one lap around your office, or taking a few deep breaths—anything that, over time, will act as your own mental circuit breaker. For some of my clients, this circuit breaker is taking a few minutes to drink a cup of coffee or looking out the window. Then you “open the door,” which means you bring your full attention to what comes next in your schedule.

Staying present and truly listening is also easier when we’re able to let go of our own agenda. For many leaders, letting go of our agenda means letting go of the noble and understandable, but at times counterproductive, desire for every conversation to be productive. By “productive,” I mean conversations with a predetermined agenda that not only gets tackled from the get-go but also discussions that produce a decision, whether some kind of fix or at least next steps. I’m not saying that time management and focus aren’t important; they are, of course, particularly when days are packed and time is precious. What I mean is learning to relate to colleagues as people is equally important and a productive use of time: people who don’t feel heard at work don’t feel respected and included so they typically don’t invest much of themselves into their job and, of course, aren’t the best version of themselves. It is about finding a balance. What about taking a few minutes at the beginning of a meeting to check in and find out how people are doing? What about spending a little time just catching up, with no agenda and without wanting to fix?

This is not easy. It takes practice and patience to know when to stop ourselves from rushing. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, Andrew realized that members of his team felt isolated. Even though they attended strings of back-to-back Zoom meetings, they’d lost the human connection that popping into someone’s office or chatting over coffee created. At the risk of adding to the video meeting fatigue, he introduced what can be described as coffee e-breaks—Zoom catch-ups with no specific work agenda, during which everyone on his team could check in with each other and get and offer support if needed.

In addition to letting go of our agenda, suspending our own judgment also helps us become better at what is known in Buddhism as “deep listening.” As soon as we react to what someone else is saying, even if only in our head, then we can no longer truly listen. We get distracted by the “noise” of our own thoughts about how wrong, misguided, or unfair the other person might be, and our irritation or anger. For most of us, however, suspending judgment isn’t a standard feature in our mental makeup, and it takes regular and consistent practice.9

Leaders who keep practicing becoming better listeners develop deeper and stronger connections with their teams, which in turn contributes to boosting their engagement and performance. Learning to listen better, however, is only one aspect of deepening and strengthening these connections. A second critical element, which in fact builds on listening, is to cultivate empathy.

Excerpted with permission from the publisher, Wiley, from The Unlocked Leader: Dare to Free Your Own Voice, Lead with Empathy, and Shine Your Light in the World by Hortense Le Gentil with Caroline Lambert. Copyright © 2024 by H2 Consulting Group, LLC. All rights reserved. This book is available wherever books and eBooks are sold.